Edward Nelson (marine biologist)

Edward William Nelson (1883–1923) was a British marine biologist and polar explorer. Educated at Clifton College, Tonbridge School and Cambridge University, he was independently wealthy.[1] He worked at the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom (MBA) in Plymouth and was member of the 1910–1913 British Antarctic Expedition. in association with E. J. Allen, he developed a simple method for culturing phytoplankton.

Edward Nelson | |

|---|---|

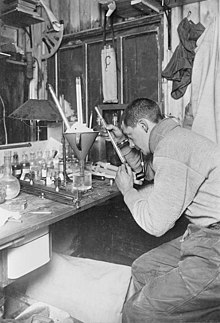

Nelson testing thermometers during the Terra Nova Expedition in 1911 | |

| Born | 1883 |

| Died | 17 January 1923 |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Clifton College Cambridge University |

| Occupation | Senior Naturalist, laboratory in Plymouth Scientific Superintendent, Fisheries Board for Scotland |

| Known for | Marine Biology Polar exploration |

Polar expedition

In 1910, he joined the British Antarctic Expedition (popularly known as "The Terra Nova Expedition") led by Robert Falcon Scott, and served as a biologist. He took part in a sledging journey to "One Ton Depot", carrying food supplies for the returning polar party. He also conducted tidal observations while at Cape Evans and was later awarded the Polar Medal along with the other Terra Nova members.[2] He was commemorated with "Nelson Cliff" at the west side of the Simpson Glacier in Antarctica (71°14′S, 168°42′E).[3]

Later career

On his return from the Antarctic, Nelson worked as Senior Naturalist at the laboratory in Plymouth, taking leave to fight with the British 63rd (Royal Naval) Division in the Gallipoli campaign, then later in the trenches of France. In 1920 the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food approached the MBA to propose that the Association undertake the manufacture of a large number of "Drift Bottles", to be used in tracking the movement of the waters of the North Sea. By this time, Nelson was the Scientific Superintendent of the Fisheries Board for Scotland, and wrote a paper on the manufacture of the drift bottles for the Association's Journal.[4]

Death

On 17 January, 1923, Nelson was found dead in his laboratory as a result of a self-injected poison.[5][6] An inquest into his death was reported in The Express and Telegraph newspaper, which was published on 01 March 1923. [6]

Over 80 years later, his daughter Barbara, then 93, died during a trip to Antarctica in 2009[7][8]

Sources and further reading

- Scott, Robert Falcon (2005). Jones, Max (ed.). Journals: Captain Scott's Last Expedition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-0192803337. OCLC 61130666.

- "Admiralty, July 24, 1913". The Edinburgh Gazette (12585). 29 July 1913. pp. 794–795.

- "Nelson Cliff". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Nelson, E. W. (1922). "On the manufacture of drift bottles". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 12: 700–716. doi:10.1017/s0025315400009723.

- "Mr. E. W. Nelson". Nature. 111 (2779): 156. 3 February 1923. Bibcode:1923Natur.111Q.156.. doi:10.1038/111156a0.

- "Scientist's tragic fate. Found poisoned in his laboratory". The Express and Telegraph. Adelaide. 1 Mar 1923. p. 4.

- Stokes, Robert (11 February 2009). "Following her father's path to Antarctica- at 93". The Southland Times. Retrieved 20 December 2018 – via PressReader.

- "Daughter of polar explorer dies near Antarctic". The Telegraph. 20 February 2009.

- Poulsom, Neville W.; Myres, John A.L. (2000). British polar exploration and research: a historical and medallic record with biographies, 1818-1999. London: Savannah. ISBN 978-1902366050.

- "Bergy Bits: The Newsletter of the Friends of the Antarctic", No. 28 April 2009

- Southward, A. J.; Roberts, E. K. (1984). "The Marine Biological Association 1884–1984: One Hundred Years of Marine Research" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 65 (1): 273. doi:10.1017/S0025315400060963.

External links

- Edward Nelson collection at the Scott Polar Research Institute