Edmund Deane

Edmund Deane (1572–c.1640) was an English physician and author. He is known for a significant work on the chemistry of mineral springs, and as an editor of alchemical tracts.

Edmund Deane | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1572 |

| Died | c.1640 |

| Nationality | English |

Life

Deane was born in Saltonstall, Halifax, West Yorkshire, and was a brother of Richard Deane, the bishop of Ossory.[1] His parents were Gilbert Deane of Saltonstall and Elizabeth, daughter of Edmund Jennings of Seilsden in Craven, and the family consisted of four sons, (Gilbert, Richard, Edmund and his twin Symon, who died at age seven). Edmund Deane was baptised on 23 March 1572; his mother's funeral was two days' later.[2]

Deane studied at Merton College, matriculating there in 1591 and graduating B.A. in 1594, and M.A. in 1597. He was licensed as a physician in 1601, and graduated M.B. and M.D. in 1608, having studied also at St Alban's Hall, Oxford. He then returned north to York and practised medicine.[3][4]

William Camidge wrote in Ye Olde Streete of Pavement (1893) that Deane occupied a house adjoining the residence of Laurence Rawden in the street called Pavement. He died in 1640, and was buried in St Crux Church, York. His will was dated 30 October 1639, and was proved at York on 14 April 1640.[2]

Spadacrene Anglica (1626)

Deane published: Spadacrene Anglica, or the English Spa Fountain (1626). This work on the spring waters at Harrogate was connected with Deane's relatively short acquaintance with Timothie Bright (Bright died in 1615, Deane moved back to York in 1614).[5] The local spring waters were sulphurous, and were recommended by a number of medical men: Bright, Deane, then Michael Stanhope, and John French.[6]

The development of the Tewit Well by William Slingsby (died 1608) from 1571 had led to a wish to promote the "English Spaw" as Bright, rector of Barwick-in-Elmet and Methley, named it in the mid-1590s.[7] Yorkshire gentry favoured the idea, and in 1625 Deane and Stanhope visited the well, cleaned it out, and took samples.[8] Deane put the argument that taking the waters in England was safer than travel to continental Europe to do so.[9]

Chemical testing of the waters was described in Spadacrene Anglica, and Stanhope's later work, based in particular on the "gall test" going back to Conrad Gesner. These are early mentions of this chemical indicator in the English literature: Gesner's ideas had been translated by Thomas Hill in his Newe Jewell of 1576, but little intervening interest was shown.[10] The tradition of chemical analysis was continued by French and Robert Witty (1660), and was praised by Samuel Hartlib.[11]

Deane mentioned four other wells around Harrogate. He also showed he was aware of the popular St Mungo's Well at Copgrove, and St Robert's Well at Knaresborough.[8] Stanhope in his 1626 work Newes out of Yorkshire described Harrogate waters, and in 1631 he discovered another spring there, which became known as St John's Well.[12]

Alchemy

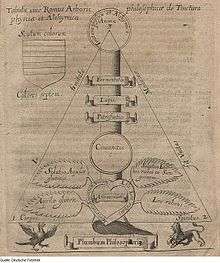

Deane also produced an edition of Samuel Norton's Latin writings (1630), published in Frankfurt.[4]

Family

Edmund Deane married twice, first to Anne, widow of Marmaduke Haddersley of Hull; the date is not known, though it was before the entry of pedigree was recorded in 1612. In 1625, he had a license at York to marry Mary Bowes of Normanton at Normanton. There does not appear to have been a family by either of his wives.[2]

Notes

- Edward Parsons (1834). The Civil, Ecclesiastical, Literary, Commercial, and Miscellaneous History of Leeds: Halifax, Huddersfield, The: Manufacturing District of Yorkshire. F. Hobson. p. 378.

- Deane, Edmund; Butler, Alex. (1922). Rutherford, James (ed.). "Spadacrene Anglica". Project Gutenberg. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Deane, Edmund (DN614E)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Mandelbrote, Scott. "Norton, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20357. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Tim Thornton (1 January 2006). Prophecy, Politics and the People in Early Modern England. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-84383-259-1.

- Bridget Heal; Ole Peter Grell (2008). The Impact of the European Reformation: Princes, Clergy and People. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7546-6212-9.

- Phyllis May Hembry (January 1990). The English Spa, 1560-1815: A Social History. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8386-3391-5.

- Phyllis May Hembry (January 1990). The English Spa, 1560-1815: A Social History. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8386-3391-5.

- Richard Butler; Wantanee Suntikul (7 May 2013). Tourism and War. Routledge. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-136-26309-5.

- Allen G. Debus (1965). The English Paracelsians. Oldbourne, London. p. 161.

- Allen G. Debus. The Chemical Philosophy. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 497 and 422. ISBN 978-0-486-15021-5.

- Phyllis May Hembry (January 1990). The English Spa, 1560-1815: A Social History. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8386-3391-5.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edmund Deane. |

- Attribution

![]()