Edgar Humann

Edgar Eugène Humann (7 May 1838 – 9 May 1914) was a French naval officer. He rose through the ranks to Admiral, and commanded the Far East naval division during the Paknam incident. He served as Chief of Staff of the French Navy in 1894–95.

Edgar Eugène Humann | |

|---|---|

Humann from the cover of Le Petit Journal 29 July 1893 | |

| Born | 7 May 1838 Paris, France |

| Died | 9 May 1914 (aged 76) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Naval officer |

Early years (1838–75)

Edgar Eugène Humann was born on 7 May 1838 in Paris.[1] His parents were Jules Humann (1809–1857), a diplomat, minister plenipotentiary and peer of France, and Isabelle Hortense Guilleminot (born 1811).[2] He joined the navy in 1855 and was a novice pilot in Le Havre and Brazil. He was made a Midshipman (Aspirant) 2nd class in the port of Toulon on 1 August 1857. He served on the Andromède in a campaign of the western shores of America.[3] Humann was promoted to Midshipman 1st class on 1 September 1859.[4] In 1860 he was on the Bretagne in the Training Squadron (escadre d'évolution) during the Syrian campaign(fr).[3]

Humann was appointed Sub-lieutenant (Enseigne de vaisseau) on 1 September 1861.[4] He was gunnery officer on the Ville-de-Paris under Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly in 1863, then the admiral's aide de camp.[3] He was appointed Lieutenant (Lieutenant de vaisseau) on 13 August 1864.[4] He served as aide de camp from 1865 to 1867 with the admiral commanding the China Sea Division.[3] On 6 March 1868 Humman was elected a member of the Société de géographie.[5] He was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour on 29 December 1866, and an Officer of the Legion of Honour on 21 January 1871.[4] In February 1871 he was gunnery officer under Admiral Louis Pierre Alexis Pothau, Minister of the Navy. In January 1873 he commanded the D'Estaing on the Newfoundland station, then in 1874 commanded the Adonis on the same station. In 1875 he was a member of the Newfoundland Fisheries Commission.[3]

Commander and captain (1875–89)

On 3 August 1875 Humann was promoted to Commander (Capitaine de frégate).[4] He studied at the school of underwater defenses in Rochefort in 1877. From 1878 to 1880 he commanded the Hirondelle in the Escadre d'évolutions.[3] He was promoted to Captain (Capitaine de vaisseau) on 10 July 1882.[4] He was second in command of the Clorinde in the Newfoundland division. In 1883 he commanded the Richelieu in the Escadre d'évolutions. On 1 January 1886 he was on the battleship Colbert as Chief of Staff of the Escadre d'évolutions under Vice-Admiral Louis Lafont(fr), the commander in chief. In 1887 he returned to the Newfoundland station commanding first the Clorinde and then the Clochetterie, using diplomacy to resolve the many problems of the fisheries.[3]

Admiral (1889–1903)

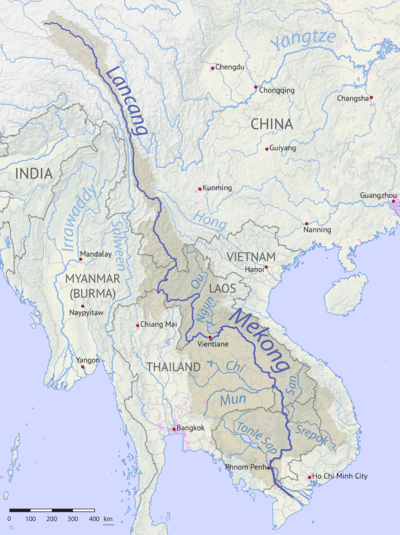

Humann was appointed Rear admiral (Contre Amiral) on 12 November 1889.[4] He was made a member of the Naval Council and a member of the Lighthouse Commission.[3] He was promoted to Commander of the Legion of Honour on 30 December 1890.[6] In 1892 he was placed in command of the Far East naval division.[3] At this time Britain and France were extending their spheres of influence in Southeast Asia. The British had taken control of Burma and the trans-Mekong Shan States, while France had established a protectorate over Annam (central and southern Vietnam). The independent kingdom of Siam (Thailand) lay between the two colonial powers, and could potentially serve as a buffer.[7]

In February 1893 Théophile Delcassé, head of the French colonial office, declared that the Mekong River defined the western limit of the French sphere of influence in Indochina.[8] Tensions rose between Siam and France with armed clashes in May and June.[9] In late June three French gunships appeared at the mouth of the Menam River to the south of the Siamese capital of Bangkok.[10] Humann commanded the French fleet.[11] The Siamese refused permission for the French to pass beyond the forts at Paknam. When they proceeded anyway the forts opened fire and grounded one of the ships. The other two continued upstream and anchored off Bangkok.[10]

On 18 July 1893, while the French warships Inconstant and Comète continued to threaten Bangkok, the French foreign minister Jules Develle served an ultimatum on Siam demanding recognition of French rights to the left bank of the Mekong and payment of reparations.[12] On 30 July Humann ordered the commander of the British H.M.S. Linnet to leave the position he had taken in front of Bangkok. This incident marked the peak of tension in the Anglo-French confrontation. The French soon apologized and the two powers settled down to protracted negotiations over buffer zones and borders.[13]

The French government claimed that Humann's actions were in defiance of (or due to failure to receive) orders instructing him not to enter the river.[14] However, instead of being reprimanded, Humann was promoted to Vice admiral on 3 February 1894. From September 1894 to November 1895 he was Chief of the General Staff of the Navy, and Director of the Cabinet of the Minister of the Navy.[3] In November 1896 Humann was commander of the Mediterranean reserve squadron. In October 1897 he was given command of the Western and Levantine Mediterranean Squadron, with the battleship Brennus as his flagship. In October 1898 he was made Inspector General of the Navy.[3] He was made a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour on 11 July 1899.[15] In 1902 he was Chairman of the Council of Marine Works. He retired from active duty in May 1903.[3]

Marriage, children and death

On 27 April 1883 Humann married Isabelle de Bouthillier-Chavigny (1858–1925). Their children included Odette (1884–1954), Marie (born 1886), Jean (1887–1904), Edgar (1888–1947), Henri (1890–1914), Joseph (1891–1957), Septime (born 1892) and Georges Odette Guilleminot (1895–1916).[2] Odette married the industrialist François de Wendel in 1905.[16] Edgar Humann died in the morning of 9 May 1914 in the 7th arrondissement of Paris.[17] He is buried in the family tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery.[18]

Notes

- HUMANN Edgar – Léonore, Doc 7.

- Pierfit.

- Rouxel.

- HUMANN Edgar – Léonore, Doc 14.

- Bulletin de la Société de géographie 1868.

- HUMANN Edgar – Léonore, Doc 12.

- Hirshfield & Hirschfield 1968, p. 27.

- Hirshfield & Hirschfield 1968, p. 31.

- Hirshfield & Hirschfield 1968, pp. 32–33.

- Hirshfield & Hirschfield 1968, p. 34.

- Hirshfield & Hirschfield 1968, p. 39.

- Hirshfield & Hirschfield 1968, p. 35.

- Hirshfield & Hirschfield 1968, pp. 39ff.

- Johnson 1894, pp. 468–469.

- HUMANN Edgar – Léonore, Doc 1.

- François de Wendel ... Annales.

- HUMANN Edgar – Léonore, Doc 3.

- HUMANN Georges (1838-1914) – AAPPL.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edgar Humann. |

Sources

- Bulletin de la Société de géographie (in French), Société de Géographie, 1868, retrieved 2018-02-25

- "François de WENDEL (1874–1949)", Annales des Mines (in French), retrieved 2017-07-11

- Hirshfield, Claire; Hirschfield, C. (March 1968), "The Struggle for the Mekong Banks 1892-1896", Journal of Southeast Asian History, Cambridge University Press on behalf of Department of History, National University of Singapore, 9 (1), JSTOR 20067667

- "HUMANN Edgar", Léonore (in French), Archives nationales, retrieved 2018-02-25

- HUMANN Georges (1838-1914) (in French), AAPPL: Association des Amis et Passionnés du Père-Lachaise, retrieved 2018-02-24

- Johnson, Alfred S., ed. (1894), The Cyclopedic Review of Current History, Volume 3, Buffalo: Garretson, Cox & Co.

- Pierfit, "Amiral Edgar HUMANN-GUILLEMINOT", geneanet (in French), retrieved 2018-02-24

- Rouxel, Jean-Christophe, "Edgar HUMANN-GUILLEMINOT", École navale (in French), retrieved 2018-02-24