Oleandomycin

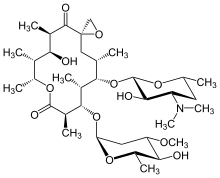

Oleandomycin is a macrolide antibiotic. It is synthesized from strains of Streptomyces antibioticus. It is weaker than erythromycin.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| E number | E704 (antibiotics) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.021.360 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C35H61NO12 |

| Molar mass | 687.868 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

It used to be sold under the brand name Sigmamycine, combined with tetracycline, and made by the company Rosa-Phytopharma in France.

Medical Use and Availability

Oleandomycin can be employed to inhibit the activities of bacteria responsible for causing infections in the upper respiratory tract much like Erythromycin can. Both can affect Staphylococcus and Enterococcus genera.

The MIC for Oleandomycin is 0.3-3 µg/ml for Staphylococcus aureus.[1]

Oleandomycin is approved as a veterinary antibiotic in some countries. It has been approved as a swine and poultry antibiotic in the United States. However, it is currently only approved in the United States for production uses.[2][3]

Brand names

- Mastalone – Oleandomycin, oxatetracycline, neomycin – Zoetis Australia and Pfizer Animal Health

- Mastiguard – Oleandomycin, oxatetracycline – Stockguard Animal Health[4]

- Formerly sold as Sigmamycine by Pfizer (Oleandomycin + Tetracycline + Vitamin C)

History

Origins

Oleandomycin was first discovered as a product of the bacterium Streptomyces antibioticus in 1954 by Dr. Sobin, English, and Celmer. In 1960, Hochstein successfully managed to determine the structure of oleandomycin. This macrolide was discovered at around the same time as its relatives erythromycin and spiramycin.[5]

Combination Drug Sigmamycine

Public interest in oleandomycin peaked when Pfizer introduced the combination drug Sigmamycine into the market in 1956. Sigmamycine was a combination drug of oleandomycin and tetracycline that was supported by a major marketing campaign. It was in fact claimed that a 2:1 mixture of tetracycline and oleandomycin had a synergistic effect on staphylococci. It was also claimed that the mixture would be effective on organisms that are mostly resistant to tetracycline or oleandomycin alone. Both of these claims were refuted by findings such as those by Lawrence P. Garrod that could find no evidence that such claims were properly substantiated.[5] By the early 1970s, Pfizer’s combination drugs were withdrawn from the market. [6] [7] [8]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action

Oleandomycin is a bacteriostatic agent. Like erythromycin, oleandomycin binds to the 50s subunit of bacterial ribosomes, inhibiting the completion of proteins vital to survival and replication. It interferes with translational activity but also with 50s subunit formation.

However, unlike erythromycin and its effective synthetic derivatives, it lacks a 12-hydroxyl group and a 3-methoxy group. This change in structure may adversely affect its interactions with 50S structures and explain why it is a less powerful antibiotic.[9]

Relative Strength

Oleandomycin is far less effective than erythromycin in bacterial minimum inhibitory concentration tests involving staphylococci or enterococci.[1] However, macrolide antibiotics can accumulate in organs or cells and this effect can prolong the bioactivity of this category of antibiotics even if its concentration in plasma is below what is considered capable of a therapeutic effect.

Chemistry

Polyketide synthesis

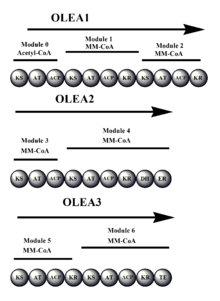

The oleandomycin synthase (OLES) follows the module structure of a type I synthase. The polyketide chain is bound through thioester linkages to the S-H groups of the ACP and KS domains (not shown).

- The gene cluster OLES1 codes for modules 0-2, module 0 containing an acetyl-CoA starter unit and all remaining moduless carrying a methyl malonyl-CoA elongation unit attached to its keto synthase unit.

- OLES2 codes for modules 3 and 4. Module 3 is notable for potentially carrying a redox-inactive ketoreductase that is responsible for retaining the unreduced carbonyl adjacent to carbon 8.

- OLES3 codes for modules 5 and 6.

The amino acid sequence similarities between OLES and 6-Deoxyerythronolide B synthase (erythromycin precursor synthase) show only a 45% common identity. Note that unlike in the erythromycin precursor synthase, there is a KS in the loading domain of OLES.[10]

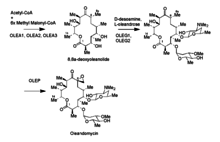

Post-PKS Tailoring

The genes OleG1 and G2 are responsible for the glycosyltransferases that attach oleandomycin’s characteristic sugars to the macrolide. These sugars are derived from TDP-glucose. OLEG1 transfers dTDP-D-desoamine and OleG2 transfers D-TDP-L-oleandrose to the macrolide ring. The epoxidation that occurs afterwards is from the enzyme encoded by OleP, which could be homologous with a P450 enzyme. The method by which OleP epoxidates is suspected to be a dihydroxylation followed by the conversion of a hydroxyl group into a phosphate group that then leaves via a nucleophilic ring closure by the other hydroxyl group.[10]

References

- Semenitz E (September 1978). "The antibacterial activity of oleandomycin and erythromycin--a comparative investigation using microcalorimetry and MIC determination". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 4 (5): 455–7. doi:10.1093/jac/4.5.455. PMID 690046. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "Drugs Transitioning from Over‐the‐Counter (OTC) to Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD) Status" (PDF). U.S Food and Drug Administration. 19 Jan 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "21 CFR 558.435 - Oleandomycin". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. 17 Sep 2001. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "Oleandomycin". Drugs.com. 16 April 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- Garrod LP (July 1957). "The erythromycin group of antibiotics". British Medical Journal. 2 (5036): 57–63. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5036.57. JSTOR 25383104. PMC 1961747. PMID 13436854.

- Podolsky SH, Greene JA (August 2011). "Combination drugs--hype, harm, and hope". The New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (6): 488–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1106161. PMID 21830965.

- Jones WF, Finland M (September 1957). "Antibiotic combinations; tetracycline, erythromycin, oleandomycin and spiramycin and combinations of tetracycline with each of the other three agents; comparisons of activity in vitro and antibacterial action of blood after oral administration". The New England Journal of Medicine. 257 (12): 536–47 concl. doi:10.1056/NEJM195709192571202. PMID 13464978.

- Pfizer Inc v. L. Richardson c., 434 vF.2D 536, 8 (United State Court of Appeals, Second Circuit 2 Nov 1970).

- Champney WS, Tober CL, Burdine R (December 1998). "A comparison of the inhibition of translation and 50S ribosomal subunit formation in Staphylococcus aureus cells by nine different macrolide antibiotics". Current Microbiology. 37 (6): 412–7. doi:10.1007/s002849900402. PMID 9806980.

- Rawlings BJ (June 2001). "Type I polyketide biosynthesis in bacteria (part B)". Natural Product Reports. 18 (3): 231–81. doi:10.1039/b100191o. PMID 11476481.