Cryptoxanthin

Cryptoxanthin is a natural carotenoid pigment. It has been isolated from a variety of sources including the fruit of plants in the genus Physalis, orange rind, papaya, egg yolk, butter, apples, and bovine blood serum.[1]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(1R)-3,5,5-Trimethyl-4-[(3E,5E,7E,9E,11E,13E,15E)-3,7,12,16-tetramethyl-18-(2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl)octadeca-1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15,17-nonaen-1-yl]cyclohex-3-en-1-ol | |

| Other names

(3R)-β,β-Caroten-3-ol Cryptoxanthol Caricaxanthin (R)-all-trans-β-Caroten-3-ol Hydroxy-β-carotene kryptoxanthin | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| E number | E161c (colours) |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C40H56O | |

| Molar mass | 552.85 g/mol |

| Melting point | 169 °C (336 °F; 442 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Chemistry

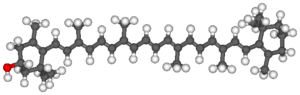

In terms of structure, cryptoxanthin is closely related to β-carotene, with only the addition of a hydroxyl group. It is a member of the class of carotenoids known as xanthophylls.

In a pure form, cryptoxanthin is a red crystalline solid with a metallic luster. It is freely soluble in chloroform, benzene, pyridine, and carbon disulfide.[1]

Biology and medicine

In the human body, cryptoxanthin is converted to vitamin A (retinol) and is, therefore, considered a provitamin A. As with other carotenoids, cryptoxanthin is an antioxidant and may help prevent free radical damage to cells and DNA, as well as stimulate the repair of oxidative damage to DNA.[2]

Recent findings of an inverse association between β-cryptoxanthin and lung cancer risk in several observational epidemiological studies suggest that β-cryptoxanthin could potentially act as a chemopreventive agent against lung cancer.[3] On the other hand, in the Grade IV histology group of adult patients diagnosed with malignant glioma, moderate to high intake of cryptoxanthin (for second tertile and for highest tertile compared to lowest tertile, in all cases) was associated with poorer survival.[4]

Other uses

Cryptoxanthin is also used as a substance to colour food products (INS number 161c). It is not approved for use in the EU[5] or USA; however, it is approved for use in Australia and New Zealand.[6]

References

- Merck Index, 11th Edition, 2612.

- Lorenzo, Y.; Azqueta, A.; Luna, L.; Bonilla, F.; Dominguez, G.; Collins, A. R. (2008). "The carotenoid β-cryptoxanthin stimulates the repair of DNA oxidation damage in addition to acting as an antioxidant in human cells". Carcinogenesis. 30 (2): 308–314. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgn270. PMID 19056931.

- Lian, Fuzhi; Hu, Kang-Quan; Russell, Robert M.; Wang, Xiang-Dong (2006). "β-Cryptoxanthin suppresses the growth of immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells and non-small-cell lung cancer cells and up-regulates retinoic acid receptor b expression". International Journal of Cancer. 119 (9): 2084–2089. doi:10.1002/ijc.22111.

- Delorenze, Gerald N; McCoy, Lucie; Tsai, Ai-Lin; Quesenberry, Charles P; Rice, Terri; Il'yasova, Dora; Wrensch, Margaret (2010). "Daily intake of antioxidants in relation to survival among adult patients diagnosed with malignant glioma". BMC Cancer. 10: 215. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-215. PMC 2880992. PMID 20482871.

- UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code"Standard 1.2.4 - Labelling of ingredients". Retrieved 2011-10-27.