Duro Ladipo

Durodola Durosomo Duroorike Timothy Adisa Ladipo (December 18, 1926 – March 11, 1978), more commonly known as Duro Ladipo was one of the best known and critically acclaimed Yoruba dramatists who emerged from postcolonial Africa. Writing solely in the Yoruba language, he captivated the symbolic spirit of Yoruba mythologies in his plays, which were later adapted to other media such as photography, television and cinema. His most famous play, Ọba kò so (The King did not Hang), a dramatization of the traditional Yoruba story of how Ṣango became the Orisha of Thunder, received international acclaim at the first Commonwealth Arts Festival in 1965 and on a European tour, where a Berlin critic, Ulli Beier, compared Ladipọ to Karajan.[1] Ladipo usually acted in his own plays.

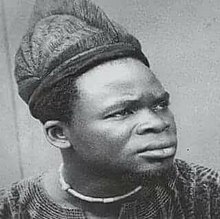

Duro Ladipo | |

|---|---|

Duro Ladipo in c. 1955 | |

| Born | Dúródọlá Dúróṣọmọ́ Dúróoríkẹ́ Timothy Adìsá Ládipọ December 18, 1926 Osogbo, Osun State, British Nigeria (now Nigeria) |

| Died | March 11, 1978 (aged 51) Osogbo, Osun, Nigeria |

| Occupation | writer, playwright, actor, producer, dramatist |

| Language | Yoruba |

| Nationality | Nigerian |

| Home town | Osogbo |

| Period | 1961-1978 |

| Notable works | Ọba kò so, Oba waja |

| Spouse | Abiodun Duro-Ladipo (m. 1964-1978) |

Early life

Durodola Durosomo (or Durosinmi) Duroorike Timothy Adisa Ladipo was born on December 18, 1926[2][3] to Joseph Oni Ladipo and Dorcas Towobola Ajike Ladipo. Many sources claim he was born in 1931, but this was most likely erroneously stated.[4] Because Ladipo was born after nine of his parent's children died before the age of 1, Ladipo was believed to an abiku.[5] Abiku, meaning born to die, is a Yoruba concept in which there are spirits that possess the body's of several children of a parent and exist to cause pain and sadness for the parents. The only way this could be solved were intense spritiual rituals made to tie the child down to this world or convince the evil spirit that its death would not bring sadness. This was why some children can be seen with unaffectionate names. Ladipo being believed to be an abiku can be seen by his many names beginning with dúró, a Yoruba word meaning to stay, wait, or remain. His name Dúródọlá means "wait for wealth," trying to convince him to stay and enjoy life, Dúróṣọmọ́ means "stay to be our child," another variation, Dúrósinmí means "stay to bury me," and Dúróoríkẹ́ means "stay to see how much we will care for you."[6] Despite the fact that both Joseph & Dorcas Ladipo were devout Anglican Christians who rejected the beliefs of their parents, they were so troubled by this that for Ladipo, they went to a traditional Ifa priest, or Babalawo.[7] After Duro survived infancy, his parents had 5 more children, including a set of twins, who all survived infancy.[8] Ladipo's great-grandfather was a drummer of the gangan (drum) & worshipper of the god Shango who escaped the Jalumi War with the help of Oderinlo, one of the war generals, because it was believed to be forbidden to kill a drummer in war. The tradition of drumming and drummaking continued with his son, Ladipo's grandfather. However, Ladipo's father, Joseph Oni, refused to follow his ancestor's footsteps and instead converted to Christianity around 1912, and became a minister at an Anglican church in Oṣogbo. Joseph wanted Ladipo to follow in his footsteps to be a preacher, however, Ladipo was influenced by his grandfather, who was also a devout worshipper of Shango & Oya and was well versed in Yoruba mythology, especially those emanating from Old Ọyọ, and Ladipo observed Ifa and Egungun festivals at Ila Orangun & Otan Ayegbaju, towns near Osogbo.

Career

Ladipọ tried hard and succeeded in exposing himself to traditional and Yoruba cultural elements, especially when living under the veil of a Christian home. At a young age, he would sneak out of the vicarage to watch Yoruba festivals. This fascination with his culture goaded him into researching and experimenting with theatrical drama and writing. After leaving Oṣogbo, he went to Ibadan, where he became a teacher. While in Ibadan he became one of the founding members of an artist club called Mbari Mbayo and became influenced by Beier. He later replicated the club in Oṣogbo, and it became the premier group for promoting budding artists and dramatists in Oṣogbo. Throughout his career, Duro Ladipọ wrote ten Yoruba folk operas combining dance, music, mime, proverbs, drumming and praise songs.

Ladipo started his personal theatre group in 1961, but he became fully established with the founding of the Mbari Mbayo Club in Oṣogbo. His popularity as the leader of a folk opera group rests on his three plays: Ọbamoro in 1962, Ọba ko so and Ọba Waja in 1964. (Ọba Waja - "The King is Dead" - is based on the same historical event that inspired fellow Nigerian playwright Wọle Ṣoyinka's Death and the King's Horseman.)[9] He also promoted Mọremi, a play about the Yoruba ancestress of the same name. He later transformed Mbari Mbayo into a cultural center, an arts gallery and a meeting point for young artists seeking to develop their talents. Duro Ladipọ wrote quite a number of plays, such as Suru Baba Iwa" and "Tanimowo Iku." Some of his plays were also produced for television. In fact, he created Bode Wasinimi for the Nigerian Television Authority, Ibadan.

In 1977, Duro Ladipo participated in FESTAC '77, the Second World Festival of Black and African Arts and Culture, in Lagos, Nigeria.

Personal life

Despite his Christian backgrounds, Ladipo was a polygamist and had 3 wives, and about 15 children.[10]In 1964, he married Abiodun Duro-Ladipo, his third wife and she became a permanent member of the troupe, she gained fame as an actress, taking main roles in all the plays performed by the company.[11][12] He died on March 11, 1978, at the age of 51, from a short illness. It is said that when he died the heavens opened, and there was sudden rain & thunder and Shango, the god of thunder and the main character of his most famous work, welcomed him into the heavens.

Notes

- Ulli Beier, p.c. (1965) to Prof. Herbert F. W. Stahlke.

- https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195382075.001.0001/acref-9780195382075-e-1140

- https://oxfordaasc.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.001.0001/acref-9780195301731-e-49221

- http://www.obafemio.com/uploads/5/1/4/2/5142021/thesis_for_oluseyi_ogunjobi.pdf

- http://www.obafemio.com/uploads/5/1/4/2/5142021/thesis_for_oluseyi_ogunjobi.pdf

- http://www.obafemio.com/uploads/5/1/4/2/5142021/thesis_for_oluseyi_ogunjobi.pdf

- http://www.obafemio.com/uploads/5/1/4/2/5142021/thesis_for_oluseyi_ogunjobi.pdf

- https://oxfordaasc.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.001.0001/acref-9780195301731-e-49221

- Soyinka, Wole (2002). Death and the King's Horseman. W.W. Norton. p. 5. ISBN 0-393-32299-8.

- https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1525/aa.1974.76.3.02a01010

- Akyeampong, Emmanuel Kwaku; Gates, Henry Louis (2012). Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5.

- Abiodun, Taiwo (26 February 2018). "Why I did not remarry, Chief Abiodun Duro-Ladipo". Taiwo's World. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

References

- Ladipọ, Duro (1972). Ọba kò so (The king did not hang) — Opera by Duro Ladipọ. (Transcribed and translated by R. G. Armstrong, Robert L. Awujọọla and Val Ọlayẹmi from a tape recording by R. Curt Wittig). Ibadan: Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan.