Dura-Europos church

The Dura-Europos church (also known as the Dura-Europos house church) is the earliest identified Christian house church.[1] It is located in Dura-Europos in Syria. It is one of the earliest known Christian churches,[2] and was apparently a normal domestic house converted for worship some time between 233 and 256, when the town was abandoned after conquest by the Persians.[3] It is less famous, smaller, and more modestly decorated than the nearby Dura-Europos synagogue, though there are many other similarities between them.

Although the fate of the church structure is unknown after occupation by ISIS, its famous frescos were removed after discovery and are now preserved at Yale University Art Gallery.[4]

History

The site of Dura-Europos, a former city and walled fortification, was excavated largely in the 1920s and 1930s by French and American teams. Within the archaeological site, the house church is located by the 17th tower and preserved by the same defensive fill that saved the nearby Dura-Europos synagogue.

The building consists of a house conjoined to a separate hall-like room, which functioned as the meeting room for the church. No prominent altar was found and archeologists are unsure where exactly it was located. In contrast the room serving as the baptistry is very developed.[5] The surviving frescoes of are probably the most ancient known Christian paintings. The "Good Shepherd", the "Healing of the paralytic" and "Christ and Peter walking on the water" are considered the earliest depictions of Jesus Christ.[6]

A wall was demolished to make space for the large assembly room. This signified the shift to "church houses" which were more permanently adapted for religious use.[7]

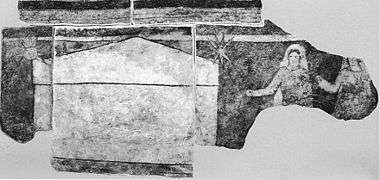

A much larger fresco depicts three women (the third mostly lost) approaching a large sarcophagus. This most likely depicts the three Marys visiting Christ's tomb[8], while another interpretation sees here the depiction of the Parable of the Ten Virgins[9] There were also frescoes of Adam and Eve as well as David and Goliath. The frescoes clearly followed the Hellenistic Jewish iconographic tradition, but they are more crudely done than the paintings of the nearby Dura-Europos synagogue.[10]

Fragments of parchment scrolls with Hebrew texts have also been unearthed; they resisted meaningful translation until J.L. Teicher pointed out that they were Christian Eucharistic prayers, so closely connected with the prayers in Didache that he was able to fill lacunae in the light of the Didache text.[11]

In 1933, among fragments of text recovered from the town dump outside the Palmyrene Gate, a fragmentary text from an unknown Greek gospel harmony account was unearthed. It was comparable to Tatian's Diatessaron, but independent of it.

Gallery

The Good Shepherd

The Good Shepherd Healing of the paralytic

Healing of the paralytic Christ and Peter walking on water

Christ and Peter walking on water Women at the tomb

Women at the tomb The Samaritan Woman by the Well

The Samaritan Woman by the Well

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dura Europos domus ecclesiae. |

- Oldest churches in the world

- Dura-Europos

- Lullingstone Roman Villa, another rare house-church from Roman Britain

References

- Snyder, Graydon F. (2003). Ante Pacem: Archaeological Evidence of Church Life Before Constantine. Mercer University Press. p. 128.

- The people are holy: the history and theology of Free Church worship by Graydon F. Snyder, Doreen M. McFarlane 2005 ISBN 0-86554-952-4 page 30

- Floyd V. Filson (June 1939). "The Significance of the Early House Churches". Journal of Biblical Literature. 58 (2): 105–112. doi:10.2307/3259855. JSTOR 3259855.

- Yale University

- Neil Xavier O'Donoghue, "Liturgical Orientation: the Position of the President at the Eucharist" in Joint Liturgical Studies No. 83

- Graydon F. Snyder, Ante pacem: archaeological evidence of church life before Constantine, pp. 129-134, (Mercer University Press, 2003) google books

- Geoffrey Wainwright (2006). The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford University Press. p. 801. ISBN 0195138864.

- Yale: "Unearthing the Christian building", p.4

- Sanne Klaver: The Brides of Christ: The Women in Procession in the Baptistery of Dura-Europos, in: Eastern Christian Art, 9 (2012-2013), pp. 63-78

- F. Snyder, Ante pacem: archaeological evidence of church life before Constantine, pp. 129-134, Mercer University Press, 2003

- J.L. Teicher, "Ancient Eucharistic Prayers in Hebrew (Dura-Europos Parchment D. Pg. 25)", The Jewish Quarterly Review New Series 54.2 (October 1963), pp. 99-109

Further reading

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, nos. 360 (fresco) and 580 (architecture), 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- C H Kraeling, The Christian Building, 1967, Yale University Press

- Clark Hopkins, The Discovery of Dura-Europos, Yale University Press, 1979

- Penny Young, Dura Europos A City for Everyman, Twopenny Press, 2014

- Michael Peppard: The World’s Oldest Church, Bible, Art and Ritual at Dura-Europos, Syria, Yale, University Press, New Haven, London 2016, ISBN 978-0-300-21399-7