Duluth Armory

The Duluth Armory is a former armory and event venue in the East Hillside neighborhood of Duluth, Minnesota, United States. It was built in 1915 for the National Guard and naval militia, and expanded in 1941. From the beginning the National Guard also rented out the drill hall as an event venue, as it provided a larger and more flexible space than any other local venue until the construction of the Duluth Arena-Auditorium in 1966.[2]

Duluth Armory | |

The Duluth Armory from the south, showing the Drill Hall (left) and Head House (center and right) | |

| |

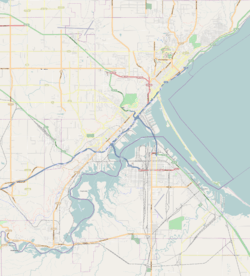

| Location | 1301–1305 London Road, Duluth, Minnesota |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 46°47′56″N 92°4′50″W |

| Area | Less than one acre |

| Built | 1915, expanded 1941 |

| Architect | Clyde W. Kelly & Owen J. Williams (original); Phillip C. Bettenburg (addition) |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical |

| NRHP reference No. | 11000324[1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 1, 2011 |

In 1978, it was purchased by the city and its use as an armory was discontinued. Since 2000, the armory has been threatened with demolition, though efforts are ongoing to renovate the building. Since 2004 a non-profit organization called the Armory Arts and Music Center has been working to rehabilitate the building as a cultural venue.[3]

The Duluth Armory was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011 for its state-level significance in the theme of military history and local significance in the theme of entertainment/recreation. It was nominated for its role as the home base of a critical port's peacekeeping and disaster response forces, and for being Duluth's largest cultural event venue until 1966.[4]

Architecture and use

The armory is located in the East Hillside neighborhood. It fronts London Road, and across the street is Leif Erickson Park.[5] The building consists of three main parts—the Head House, the Drill Hall, and an addition built in 1941. The exterior walls are variegated dark brown brick.[5]

The Drill Hall is 190 feet 8 inches (58.12 m) long and 93 feet (28 m) wide.[5] Within Minnesota, at the time of construction, the size of the armory's Drill Hall was second only to the 1907 armory in Minneapolis, and the Duluth Armory as a whole was larger.[6] The Drill Hall served as a venue for expositions, trade shows, musical groups, and recreational and sporting events.[7]

The Head House contained administrative offices, classrooms, and service areas.[8] It is 200 feet 2 inches (61.01 m) long by 34 feet (10 m) wide and is 69 feet (21 m) tall.[5]

The 1941 addition is 154 feet 8 inches (47.14 m) long and 45 feet (14 m) wide, extending 11 feet 4 inches (3.45 m) beyond the rear wall of the Drill Hall.[5]

History

Planning and construction

A prior armory was built in Duluth in 1896 for the Minnesota National Guard.[9][lower-alpha 1] In 1899, Minnesota created a naval reserve, introducing a two-division unit in Duluth.[9] The addition strained the available space in the armory. Attempts were made to use some of the first floor, but this conflicted with existing commercial activity.[11]

In September 1913, the city of Duluth announced that it would deed property for a new armory, to be located at the end East 13th Avenue along the waterfront. The proposed location was opposed by some residents; the property was in Lake Shore Park, which had been donated to the city by the Saint Paul and Duluth Railroad under the condition than it remain parkland in perpetuity. The city argued that it was the optimal location and the building would not negatively impact the park. An article in the Duluth News Tribune, published a few days later, showed a site plan and argued that the new armory would "only occupy a corner of the park."[11]

Planning proceeded slowly, despite the urgent need for more spacious facilities. By November 1914, the planned building site had moved across London Road, apparently heeding earlier protests; the new location had previously been purchased by the city for $16,000. The state of Minnesota allocated $112,500 for the armory, and after some delay, bidding began in February 1915. The contract was earned by George H. Lounsberry of Duluth.[12] The building, estimated to cost $107,410, was designed by architects Clyde W. Kelly and Owen J. Williams.[12][lower-alpha 2] Their design broke with the tradition of earlier armory styles in Minnesota. Instead of using the castle-like features seen in the St. Peter Armory, for example, the architects opted for Beaux-Arts classicism. The sleek and simple style was a prime example of the new era of armory design. The building, with over 107,000 interior square feet (9,900 m2), was the biggest armory in the state. It had living quarters for Guardsmen, offices, training facilities, and public event space.[13]

The project came in over budget at $150,000 (equivalent to $3,790,954 in 2019). $103,000 was paid by the state, $18,500 by the city, and the remainder by "public-spirited" citizens. The new armory held its grand opening on November 22, 1915. The celebration was attended by Governor Winfield S. Hammond, former governor Adolph Eberhart, and other officials.[6]

Military use and expansion

Duluth's National Guardsmen went overseas when the U.S. entered World War I in 1917. To protect citizens and resources at home, the state created the Minnesota Home Guard. Home Guard units, including those based in the armory, were called to action twice during the course of the war. They organized relief efforts when a tornado hit the city of Tyler and after a wildfire tore through the northeastern part of the state.[13]

In September 1940, an expansion of the armory was announced by Sidney L. Stolte of the Work Projects Administration. Plans drafted by architect Phillip C. Bettenburg in November 1940 featured an expanded stage, classrooms, a kitchen, and restrooms.[14] The addition was a brick, multi-story structure along the northern side of the armory, designed with a flat roof to accommodate a fly loft for the stage.[14][5] Work on the addition, which cost $95,896, began mid-April 1941 and continued into winter.[15]

As the country's farthest inland port, Duluth prepared the armory for possible attack during World War II with blackout screens and lightproof paint. A Minnesota State Guard formed to carry out civil defense. Its men, named the "Monday Night Soldiers", met at the armory once a week for training.[13]

Entertainment use

While military activity was the initial concern of the Duluth Armory, the building has hosted social and cultural events since it opened. Its early years saw an automobile show, charity events, and regular expos and conventions.[13]

Famous public figures and performers drew crowds to the armory. President Harry S. Truman, Senator Hubert Humphrey, and former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt gave speeches. John Philip Sousa's marching band performed in January 1920, and the New York Philharmonic came in 1921. The Duluth Civic Symphony Orchestra held its annual concert series at the armory.[13]

By the middle of the century, big-name acts were common. Johnny Cash, Liberace, Louis Armstrong, Sonny & Cher, Diana Ross and the Supremes, and the Beach Boys all entertained Duluth from the armory’s stage.[13]

On January 31, 1959, Buddy Holly performed at the armory; he died in a plane crash days later on February 3. A young Bob Dylan attended the performance, which he cited as an inspiration at the 1998 Grammy Awards when he received Album of the Year for Time Out of Mind.[16][17] He said,

I just want to say that when I was 16 or 17 years old, I went to see Buddy Holly play at Duluth National Guard Armory and I was three feet away from him… and he looked at me. And I just have some kind of feeling that he was – I don’t know how or why – but I know he was with us all the time we were making this record in some kind of way.[16]

Disuse and rehabilitation efforts

The prosperity of the post-war years prompted many states to tear down their out-of-date armories and build modern facilities. In 1963, Duluth built a new center for its 800-man Army Reserve.[13] The value of the armory as a public venue greatly decreased with the construction of the Duluth Arena-Auditorium in 1966, which had more seating and modern amenities.[18] In 1977, the National Guard announced plans to build a new armory in Duluth and in 1978, the city purchased the historic armory from the state for $160,000. The Head House was used for offices and the Drill Hall served as a garage for maintenance vehicles. The Drill Hall also stored some raw materials, and its original wood floor no longer exists.[19]

After years of vacancy and little upkeep, the armory was first threatened with demolition in 2001.[13] The city made efforts to study the cost of repairing the building for reuse. A Duluth Planning Department report from April 2002 estimated it would cost $235,000 for asbestos abatement and $1.3 million for lead abatement from its time as a shooting range.[20] On May 24, 2004, the building was purchased by the Armory Arts and Music Center for $1.[3][19]

The armory was damaged by flooding in June 2012 from Chester Creek, which runs beneath the building. The creek breached its culvert, creating a "significant sized hole" in the basement allowing water to enter, which damaged electrical systems, disturbed asbestos, and led to an accumulation of debris and sediment within the building. The culvert is owned by the city, but fortunately the flood repairs were eligible for funding through state emergency highway funding. A six-month stay from demolition was granted by the city in August 2012 because restoration was progressing.[20] In April 2013, heavy snow damaged a parapet on the Drill Hall, causing a number of bricks to fall to the ground.[21][22]

Notes

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Atwood, Stephanie K.; Charlene K. Roise. "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Duluth Armory (draft)" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-11. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The AAMC". Duluth Armory. 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-15.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 12.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 8.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 20.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, pp. 26–28.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 15.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 17.

- Koop, Michael; Morris, Chris (2006). "NRHP Nomination: Duluth Commercial Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service: 72.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 18.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 19.

- Heneghan, Natalie (2016-04-19). "Duluth Armory". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2019-06-15.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 25.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, pp. 25–26.

- Walsh, Jim (May 18, 2012). "Duluth, Hibbing throwing weekend parties for birthday boy Bob Dylan". MinnPost. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- Lawler, Christa (February 5, 2011). "Duluth Armory gets a million bucks" (PDF). Duluth News Tribune. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, pp. 29–30.

- Atwood & Roise 2011, p. 30.

- "Flood cleanup could fix Duluth Armory's ills". Duluth News Tribune. November 27, 2012. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- "Winter Weather Takes Its Toll on Duluth Armory". Fox 21 News. April 16, 2013. Archived from the original on July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- "Duluth Armory Restoration One Brick at a Time". Fox 21 News. June 1, 2013. Archived from the original on July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

Bibliography

- Atwood, Stephanie K.; Charlene K. Roise. "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Duluth Armory (draft)" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-11. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Duluth Armory. |