Drums in the Night

Drums in the Night (Trommeln in der Nacht) is a play by the German playwright Bertolt Brecht. Brecht wrote it between 1919 and 1920, and it received its first theatrical production in 1922. It is in the Expressionist style of Ernst Toller and Georg Kaiser. The play—along with Baal and In the Jungle—won the Kleist Prize for 1922 (although it was widely assumed, perhaps because Drums was the only play of the three to have been produced at that point, that the prize had been awarded to Drums alone); the play was performed all over Germany as a result.[2] Brecht later claimed that he had only written it as a source of income.[3]

| Drums in the Night | |

|---|---|

| Written by | Bertolt Brecht |

| Characters | Andreas Kragler, missing World War I soldier Anna Balicke, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Balicke Karl Balicke Amalie Balicke Friedrich Murk, Anna's fiancé Babusch, a journalist Maid Waiter Marie, a prostitute Glubb, a bartender Bulltrotter, newspaper vendor Auguste, a prostitute Drunk[1] |

| Date premiered | 29 September 1922 |

| Original language | German |

| Genre | Comedy in Five Acts |

| Setting | Berlin, January 1919 |

Drums in the Night is one of Brecht's earliest plays, written before he became a Marxist, but already the importance of class struggle in Brecht's thinking is apparent. According to Lion Feuchtwanger, the play was originally entitled Spartakus.[4] Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg of the Spartacist League—who were instrumental in the 'Spartacist uprising' in Berlin in January 1919—had only recently been abducted, tortured and killed by Freikorps soldiers.

Plot summary

Brecht's play revolves around Anna Balicke, whose lover (Andreas) has left to fight in World War I. The war is now over but Anna and her family have not heard from him for four years. Anna's parents try to convince her that he is dead and that she should forget him and marry a wealthy war-materials manufacturer, Murk. Anna agrees to this arrangement eventually, just as Andreas returns, having spent the missing years as a prisoner-of-war in some remote location in Africa. Believing that the poor proletarian Andreas cannot provide the kind of life for Anna that the bourgeois Murk can, Anna's parents encourage her to stick to her agreement. Eventually Anna leaves Murk and her parents and, against the backdrop of the Spartacist uprising, searches for Andreas. In the final scene they are re-united; to the sound of "a white wild screaming" from the newspaper buildings above, they walk away together.

The play dramatizes many of the grievances of the Spartacists in their uprising. The soldiers returning from the front felt that they had been fighting for nothing and that what they had before they left had been stolen. Murk, the war-profiteer who did not fight and who instead made a fortune from the fighting, and who attempts to steal the soldier's fiancée, symbolizes that feeling by the working class of having been cheated.

Production history

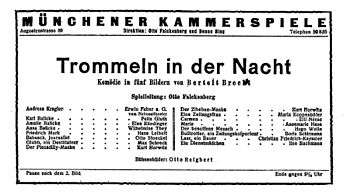

Drums in the Night, a "Comedy in Five Acts by Bertolt Brecht", was given its premiere at the Munich Kammerspiele, opening on 29 September 1922. Otto Falckenberg - head of the Kammerspiele and renowned champion of new, controversial dramas in Weimar Germany - directed, set-design was by Otto Reigbert, and the cast included Erwin Faber (as a Guest from the National Theatre of Munich, the Residenztheater) in the main role of Andreas Kragler, Max Schreck (as Glubb), Hans Leibelt, Kurt Horwitz and Maria Koppenhöfer.

The play received another production at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin, also directed by Falckenberg, which opened on 20 December 1922, with a cast of leading actors then in Berlin, including Alexander Granach as the soldier Andreas Kragler.[5]

Falckenberg, who was the head of the Kammerspiele along with Benno Bing, directed the play in a manner that we would not now recognize as 'Brechtian', utilizing the angular, contorted poses typical of the theatre of Expressionism.[6] Similarly, Reigbert's design consisted of contorted, angular lines and foreshortened perspectives (similar to those used in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in 1920).[7] "Brecht's sense of irony was misunderstood", Meech suggests; he was "far from happy with the result."[8]

Elements of Expressionism, or perhaps "realistic-Expressistic" elements (according to Erwin Faber),[9] can be found in designs for the Munich production. Reigbert's rendering for the set design for Act V of Drums in the Night, for example, contains a figure standing by the bridge that is very much like Edvard Munch's figure (also standing by a bridge) in his painting of 1893, The Scream.

According to Erwin Faber, whom Brecht had requested to play the principal role of Andreas Kragler, a German soldier who returns home after to the war:

- The play was...expressionistic, that is, realistic-expressionistic. It was born of the times, and I played it as such...By the time Brecht arrived, the period of Expressionism in Munich had already passed...The heyday of Expressionism came in the aftermath of World War I, when we were all exhausted by the war: hunger, suffering, and grief was in every family who had lost a loved one. There was a tension that could only be resolved by an outcry...[Drums in the Night] was perhaps one of the last dramas to be played expressionisitically.[10]

Works cited

- Brecht, Bertolt. 1922. Drums in the Night. Trans. John Willett. In Collected Plays: One. Ed. John Willett and Ralph Manheim. Bertolt Brecht: Plays, Poetry and Prose Ser. London: Methuen, 1970. ISBN 0-416-03280-X. p. 63-115.

- Meech, Tony. 1994. "Brecht's Early Plays." In The Cambridge Companion to Brecht. Ed. Peter Thomson and Glendyr Sacks. Cambridge Companions to Literature Ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41446-6. p. 43-55.

- Molinari, Cesare. 1975. Theatre Through the Ages. Trans. Colin Hamer. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-29448-9.

- McDowell, W. Stuart. 2000. "Acting Brecht: The Munich Years", The Brecht Sourcebook, Carol Martin, Henry Bial, editors (Routledge, 2000) p. 71 - 83.

- Sacks, Glendyr. 1994. "A Brecht Calendar." In The Cambridge Companion to Brecht. Ed. Peter Thomson and Glendyr Sacks. Cambridge Companions to Literature Ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41446-6. p.xvii-xxvii.

- Willett, John. 1967. The Theatre of Bertolt Brecht: A Study from Eight Aspects. Third rev. ed. London: Methuen, 1977. ISBN 0-413-34360-X.

- Willett, John and Ralph Manheim. 1970. "Introduction." In Collected Plays: One by Bertolt Brecht. Ed. John Willett and Ralph Manheim. Bertolt Brecht: Plays, Poetry and Prose Ser. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-03280-X. p.vii-xvii.

- Calabro, Tony. 1990. Bertolt Brecht's Art of Dissemblance. Longwood Academic.

Notes

- Brecht, Bertolt (1992). Die Stücke von Bertolt Brecht in einem Band. Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Willett (1967, 23-24), Willett and Manheim (1970, viii-ix), and Meech (1994, 50).

- Willett and Manheim (1970, ix).

- Willett (1967, 24).

- Willett (1967, 23-24) and Willett and Manheim (1970, viii-ix).

- McDowell (2000, 73).

- See Willett and Manheim (1970, viii); a photograph from this production is reproduced in Willett (1967, 23). There is a good colour reproduction of Reigbert's sketch for his design for the production in Molinari (1975, 306).

- Meech (1994, 50).

- McDowell (2000, 76).

- McDowell (2000, 74-5).