Drillship

A drillship is a merchant vessel designed for use in exploratory offshore drilling of new oil and gas wells or for scientific drilling purposes. In most recent years the vessels are used in deepwater and ultra-deepwater applications, equipped with the latest and most advanced dynamic positioning systems.

History

The first drillship was the CUSS I, designed by Robert F. Bauer of Global Marine in 1955. The CUSS I had drilled in 400 feet deep waters by 1957.[1] Robert F. Bauer became the first president of the Global Marine in 1958.[1]

In 1961 Global Marine started a new drillship era. They ordered several self-propelled drillships each with a rated centerline drilling of 20,000 foot-wells in water depths of 600 feet. The first was named CUSS (Glomar) II, a 5,500-deadweight-ton vessel, Costing around $4.5 million. Built by a Gulf Coast shipyard, the vessel was almost twice the size of the CUSS I, and became the world's first drillship built as new construction which set sail in 1962.[1]

In 1962 The Offshore Company elected to build a new type of drillship, larger than that of the Glomar class. This new drillships would feature a first ever anchor mooring array based on a unique turret system. The vessel was named Discoverer I. The Discoverer I had no main propulsion engines,[1] meaning they needed to be towed out to the drill site.

Application

The drillship can be used as a platform to carry out well maintenance or completion work such as casing and tubing installation, subsea tree installations and well capping. Drillships are often built to the design specifications set by the oil production company and/or investors.

From the first drillship CUSS I to the Deepwater Asgard the fleet size has been growing ever since. In 2013 the worldwide fleet of drillships tops 80 ships, more than double its size in 2009.[2] Drillships are not only growing in size but also in capability with new technology assisting operations from academic research to ice-breaker class drilling vessels. U.S. President Barack Obama's decision in late March 2010 to expand U.S. domestic exploratory drilling seems likely to increase further developments of drillship technology.[3]

Design

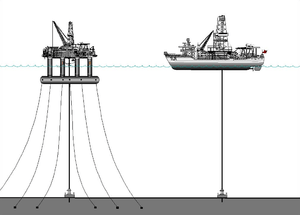

Drillships are just one way to perform various types of drilling. This function can also be performed by semi-submersibles, jackups, barges, or platform rigs.

Drillships have the functional ability of semi-submersible drilling rigs and also have a few unique features that separate them from all others. First being the ship-shaped design. A drillship has greater mobility and can move quickly under its own propulsion from drill site to drill site in contrast to semi-submersibles and jackup barges and platforms. Drillships have the ability to save time sailing between oilfields worldwide. A drillship takes 20 days to move from the Gulf of Mexico to the Offshore Angola. Whereas, a semi-submersible drilling unit must be towed and takes 70 days.[4] Drillship construction cost is much higher than that of a semi-submersible. But although mobility comes at a high price, the drillship owners can charge higher day rates and get the benefit of lower idle times between assignments.[4]

The table below depicts the industry's way of classifying drill sites into different vintages, depending on their age and water depth.[4]

| Drillship | Launch Date | Water Depth (ft.) |

|---|---|---|

| CUSS I | 1961 | 350 |

| Discoverer 534 | 1975 | 7,000 |

| Enterprise | 1999 | 10,000 |

| Inspiration | 2009 | 12,000 |

The drilling operations are very detailed and in depth. A simple way to understand what a drillship is to do in order to drill, a marine riser is lowered from the drillship to the seabed with a blowout preventer (BOP) at the bottom that connects to the wellhead. The BOP is used to quickly disconnect the riser from the wellhead in times of emergency or in any needed situation. Underneath the derrick is a moonpool, an opening through the hull covered by the rig floor. Some of the modern drillships have larger derricks that allow dual activity operations, for example simultaneous drilling and casing handling.

Types

There are different types of offshore drilling units such as the oil platform, jackup rig, submersible drilling rig, semi-submersible platform and of course drillships. All drillships have what is called a ”moon pool”. The Moon pool is an opening on the base of the hull and depending on the mission the vessel is on, drilling equipment, small submersible crafts and divers may pass through the moon pool. Since the drillship is also a vessel, it can easily relocate to any desired location. But due to their mobility, drillships are not as stable compared to semi-submersible platforms. To maintain its position, drillships may utilize their anchors or use the ship's computer-controlled system on board to run off their Dynamic positioning.[5]

Chikyū

One of the world's renowned drillship is Japan's ocean-going drilling vessel the Chikyū, which actually is a research vessel. The Chikyū has the remarkable ability to drill four miles down the seabed, which brings it at a depth of 23,000 feet below the seabed, bringing that to two to four times that of any other drillship.[6]

Dhirubhai Deepwater KG1

In 2011 the Transocean drillship the Dhirubhai Deepwater KG1 set the world water-depth record at 10,194 feet of water (3,107 meters) while working for Reliance - LWD and Directional drilling done by Sperry Drilling in India.[7]

Drillship operators

- Diamond Offshore Drilling

- International Ocean Discovery Program

- Noble Corporation

- Seadrill

- Transocean

- Türkiye Petrolleri Anonim Ortaklığı (TPAO)

- Valaris plc

References

- Schempf, F. (2007). Pioneering Offshore : The Early Years. [Tulsa, OK]: PennWell Custom Pub..

- "Drillship Building Statistics". Archived from the original on 2009-09-17.

- Broder, John M.; Krauss, Clifford (March 31, 2010). "Risk Is Clear in Drilling; Payoff Isn't". The New York Times.

- Leffler, W. , Sterling, G. , & Pattarozzi, R. (2011). Deepwater Petroleum Exploration & Production : A Nontechnical Guide. Tulsa, Okla.: PennWell Corp.

- SOS-HOTLO. (n.d.). Off shore drilling. off shore drilling. Retrieved April 4, 2014, from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-19. Retrieved 2014-04-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Pacella, R. (2010, April 1). How It Works: The Deepest Drill. Popular Science. Retrieved April 4, 2014, from http://www.popsci.com/technology/article/2010-03/deepest-drill

- Transocean Ltd. Transocean Historical Timeline. Retrieved from http://www.deepwater.com/Prebuilt/timeline/ Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Drilling ships. |