Drei Kronen & Ehrt

Drei Kronen & Ehrt is a former mine in the Harz Mountains of central Germany. It is located in the parish of Elbingerode in the county of Harz (Saxony-Anhalt). The mine extracted pyrite. Since 1992 it has been used, albeit not continuously, as a visitor mine.

Entrance of the Upper Mill Valley Gallery (Oberen Mühlentalstollen) | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Location | Elbingerode (Harz) |

| Production | |

| Products | calcite |

| History | |

| Opened | 1530 |

| Active | Grube Himmelsfürst, Grube Einheit |

| Closed | 31 July 1990 |

| Owner | |

| Company | VEB Bergbau- und Hüttenkombinat Freiberg |

Geography

Location

The mine lies in the Lower Harz mountains between Elbingerode and Rübeland (both villages in the borough of Oberharz am Brocken) on the B 27 federal road. It is located on the northeastern flank of the Bodenberg hill (491.1 m above NN) at an elevation of about 445 m above NN.[1] North of the road, in the direction of the Galgenberg, is the limestone opencast mine of Fels-Werke. The Rübeland Railway runs past the site, parallel to the B 27, from which an industrial siding branches into Fels-Werke.

History

Iron ore mining from the Middle Ages to the 19th century

In the area around the present-day iron ore was mined in earlier times. A Grube Himmelsfürst was first mentioned in 1530 in the records. In the immediate vicinity of the present day visitor mine the Großer Graben, an opencast mine, was mentioned for the first time in 1582. By the mid-19th century mining activity had reached a depth of about 40 metres. The hitherto natural drainage was no longer possible at this depth, so that water had to be pumped out with hand pumps. From 1867 to 1871 the Count of Stolberg-Wernigerode had the so-called Gräflichen Stollen ("Comital Adit") built to drain the water. Its name was changed in 1890 after the elevation of the count to a prince into the Fürstlicher Stollen ("Princely Adit"). In driving the adit a hitherto unknown deposit of pyrite was discovered that, initially, was not mined. In order to be able to transport the iron ore from the Großer Graben better, a second gallery was built from 1887 to 1889 seven metres above the Fürstlicher Stollen; this was the Oberer Mühlentalstollen. It ran to the deepest point of the open mine.

Pyrite mining from 1890 to 1927

In the early 1890s, pyrite was also extracted, initially in small quantities. The expanding chemical industry used the pyrite as a reactant for the manufacture of sulphuric acid. By 1901 20,000 tonnes had been extracted. In 1903, pyrite mining was temporarily halted, because larger mineral deposits were superseding the smaller local suppliers. There followed a period of variable production. With the advent of the First World War production climbed again. All the ore fields in the vicinity of the Großer Graben were now owned by Drei Kronen und Ehrt. The description Drei Kronen ("Three Crowns") stood for the three ore pits, the name Ehrt for the pyrite field.

During the worldwide economic crisis in the 1920s, production was halted. A cable car built for the Großer Graben was decommission in 1921 and dismantled in 1922. In 1926 the opencast mine was closed due to exhaustion of the ore. In 1927, 25 miners and one foreman (Steiger) still worked underground, extracting iron ore.

Nazi era

In the wake of Germany's rearmament prior to the Second World War, production was restarted in 1935, underpinned by a national production programme. The main shaft reached a depth of 82.5 metres in 1938. In addition to the iron ore and manganese needed as raw materials for the production of steel, pyrite was also mined. In this period efforts were made to carry out a comprehensive survey of the area around the pit in order to uncover further deposits of pyrite. In the event, pyrite as well as low grade ores were found.

In 1943, 333 people worked in the mine. These were mainly forced labourers or foreign workers. In addition to 76 German miners, there were 149 men from the Soviet Union, 74 Italians, 17 Poles, 10 Czechs and 7 Belgians at Drei Kronen & Ehrt. The foreigners were housed in three barrack blocks on the site.

Production climbed to 8,200 tonnes per month, but the planned figures were usually not attained. As a result of the increasingly poor supply towards the end of World War II, production figures fell again in 1944. In February 1945, only 200 tons of manganese ore and 2,230 tons of pyrite were mined. The last regular shift took place on 13 April 1945. For two days, allied troops had only been 10 kilometres away. Relief work continued to be carried out until 18 April, when the power went out and the pumps failed. U.S. troops peacefully occupied the mine site. They searched the above-ground facilities on 21 April and then withdrew. There was looting and destruction, mainly by the forced labourers and foreign workers still remaining in the region.[2] As a result, production records for the period before 1945 were largely lost.

It is assumed that in June 1945 the mine was flooded up to its natural outlet above the Fürstlicher Stollen. [2] Production could not therefore be resumed at first, despite urgent requests, for example from Central German Rayon (Mitteldeutsche Zellwolle). They made do with low grade ore that still lay on the tip. By expropriation, Drei Krone & Ehrt became the property of the Province of Saxony. After a few weeks, pyrite production was resumed, initially only at the level of the adit. From December 1946 mining also began on the 77m level.

Post-war period to closure, 1945-2000

On 1 January 1945, the site was renamed Grube Einheit ("Unity Pit"). The name stood for the German Unity still striven for at that time by East Germany. Although this goal was later no longer in the national interest, the name stuck. The pyrite deposit mined here was the only one on the territory of the GDR, and covered 30% of its sulphur needs. Up to 150,000 tons were extracted annually. In 1964, however, the supply of pure ores was exhausted and they had to rely on ores with a lower sulphur content. Instead of a sulphur fraction of 40 to 45%, the ore now contained only 21%. The use of the fluidized bed process for sulphur recovery was no longer possible. In preparation for this situation, new ways to process the ore had been sought since 1957. In addition, efforts were made to locate new deposits nearby. Both were ultimately successful, so that large scale investments were made in the mining facilities.

A mine water treatment plant, a boiler room fired by brown coal and a new administration building with a coop, or locker room, were constructed. In addition to a remodelling of the mine building, a new shaft was sunk in 1959. It descended to the 15th level at a depth of 460 metres; 80 metres deeper than before. Three existing shafts were thus replaced by it. Above ground, a treatment plant with crushers and a flotation facility were built. In addition, a storage hall and a railway loading facility were created. In 1965 the mine employed 515 people.

Thanks to the new processing technique, they were now able to increase sulphur content to 42%, the grain size was well below a millimetre, however, which several hitherto declining operations could not work. About 95% of the output was delivered to the sulphuric acid plant of Bergbau- und Hüttenkombinat Albert Funk Freiberg. The largest amount of sulphur was produced in 1971, with 56,559 tons. The quantity of ore extracted reached a maximum in 1973 of 381,144 tons. In the following years, volumes declined continuously. From 1978, the GDR increasingly imported elemental sulphur from Poland. In 1989, the last full year of production, 237,000 tons of ore were extracted, yielding 30,500 tons of sulphur. The number of employees had already sunk during East German days to 427 employees. Through the use of more modern mining equipment, the pit achieved an ore extraction of 50 tonnes per man per shift, even internationally - based on the raw ore quantities - of considerable value.[3]

After political changes of 1989 it became clear that the cost of sulphur extraction was clearly to high in comparison with international levels. The pit now belonged to the Treuhandanstalt. On 1 May 1990, the operating agreement of the Harzbergbau GmbH Elbingerode was founded. The firm was however was directed by the Treuhandanstalt. Missing payments led to difficulties in the payment of wages, so that a loan had to be taken out. Initially, it was planned to cease production in 1991. The actual closure took place, however, as early as 31 July 1990. Symbolically, the last mine cart was hauled on 4 December 1990, the anniversary of Saint Barbara, the miners' patron saint. The exit of the specially decorated cart was paid little attention by the 116 employees at that time. The mine had produced a total of about 13 million tonnes of ore.

Visitor mine from 1992

An initial idea, to make parts of the Schwefelkiesgrube Einheit ("Unity Pyrite Pit") - still operating then as a Volkseigener Betrieb works - accessible to the public emerged as early as 1989. The technical director of mine suggested making the first level of the facility open to visitors. The idea did not come to fruition.

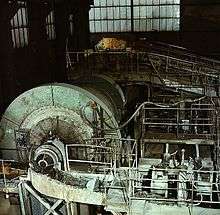

But in February 1990, seven miners founded the Friends of the Drei Kronen & Ehrt Visitor Mine (Förderverein Besucherbergwerk Drei Kronen & Ehrt e.V.). By 2001, the number of members had increased to 45. In 1990, a job creation programme was awarded, in which 21 former employees set to work on the construction of a visitor mine. The buildings needed for the show mine were restored, others demolished. Suitable machines were transported from the deeper levels of the mine to the public area. New tracks were laid, old lines made passable and lighting installed. Mine carts were converted to carry passengers.

The first visit took place on 22 May 1992, and limited guided tours were conducted from July 1993. The visitor mine was formally opened on 1 July 1994. The job creation schemes were phased out at the same time; there were now 13, later only 9, full-time employees working for the visitor mine. With subsidies the environment was improved and the works yard could be paved. The number of visitors rose from 21,000 in 1994 to 35,000 in 2001. In 2009, the operation of the visitor mine was closed. The exhibition part of the mine was leased to a work support company. On 19 December 2011, the visitor mine was reopened.[4]

The Gräflicher or Fürstlicher Stollen marks the start of today's visitor mine. The Obere Mühlentalstollen has acted since 1993 as an entrance to the visitor mine.

Walking

Drei Kronen und Ehrt is No. 61[5] in the system of checkpoints in the Harzer Wandernadel hiking network. The checkpoint is located a few metres southeast in front of the entrance gateway (51°45′49.5″N 10°49′35.7″E) of the visitor mine.

Literature

- Horst Scheffler, Das Elbingeröder Besucherbergwerk "Drei Kronen & Ehrt", Elbingerode 2002

References

- Saxony-Anhalt-Viewer

- Horst Scheffler, Das Elbingeröder Besucherbergwerk "Drei Kronen & Ehrt", Elbingerode 2002, page 20

- Horst Scheffler, Das Elbingeröder Besucherbergwerk "Drei Kronen & Ehrt", Elbingerode 2002, page 23

- Hammerschläge auf den Hosenboden und "Fahrt frei!" ins Besucherberbergwerk, Artikel der Tageszeitung Volksstimme dated 20 Deczember 2011

- Harzer Wandernadel: Stempelstelle 61 – Drei Kronen und Ehrt Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine at harzer-wandernadel.de

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schwefelkiesgrube Elbingerode. |

- "Die Kluft- und Schlottencalcite der VHMS-Lagerstätte Elbingeröder Komplex bei Elbingerode im Harz / Sachsen Anhalt in Deutschland". Archived from the original on 2016-05-07. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- Official website of the visitor mine

- "Grube Einheit (Drei Kronen und Ehrt)". Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- Klaus Stedingk (2002). "Potenziale der Erze und Spate in Saxony-Anhalt". Mitteilungen zu Geologie und Bergwesen von Saxony-Anhalt, Beiheft 5 (2002) Rohstoffbericht 2002: Verbreitung, Gewinnung und Sicherung mineralischer Rohstoffe in Saxony-Anhalt; LAGB. Archived from the original (pdf 4.82 MB) on 2010-03-21. Retrieved 2010-03-21.