Dungeonquest

Dungeonquest (sometimes known as Dungeon Quest) is a fantasy adventure board game for 1-4 players designed by Dan Glimne and Jakob Bonds and originally published in Sweden in 1985; an English version was published by Games Workshop in 1987.

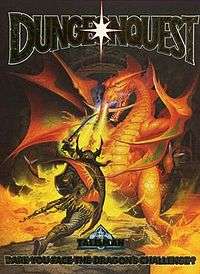

Dungeonquest as published by Games Workshop | |

| Designer(s) | Dan Glimne Jakob Bonds |

|---|---|

| Publisher(s) | Brio AB Games Workshop Schmidt Spiele |

| Players | 1-4 |

| Setup time | 10 minutes |

| Playing time | 1 hour |

| Random chance | High |

| Skill(s) required | Strategic planning |

Publication history

The game was designed by Dan Glimne and Jakob Bonds and published in Sweden in 1985 as Drakborgen ("Dragon Fortress")[1] by Alga AB (later bought out by Brio AB). It was first published in English in 1987 by Games Workshop; the English version included plastic Citadel Miniatures for characters.[1]

In Sweden, Alga AB released an expansion called Drakborgen II in 1987. Games Workshop broke the Swedish expansion into two supplements:

- Heroes for Dungeonquest (1987) adds twelve new heroes with new mechanics and special abilities, and a handful of additional cards and tokens

- Dungeonquest Catacombs (1988), adds another 20 room tiles, as well as 28 additional cards for monsters, encounters and objects. This expansion also adds the ability for players to travel underneath the main game board, albeit without any accompanying catacombs game board.

Fantasy Flight Games introduced a new version of the English-language game at Gen Con in 2010.

The Swedish edition is still being published by Alga as Drakborgen: Legenden ("Dragon Fortress: The Legend").

Components

The Games Workshop version of the game includes:[1]

- 20-page rulebook

- 6-piece gameboard

- 115 room tiles, counters and tokens

- 174 playing cards

- dice

- 4 plastic miniatures

Plot

The object of the game is to enter the ruins of Dragonfire Castle at dawn when the castle's guardian dragon falls asleep, navigate a labyrinth to the dragon's hoard at the center of the castle, and exit the castle. The game ends at sunset; any characters still in the castle at that point are automatically killed by the dragon. The player who successfully escapes from the castle with the largest amount of treasure is the winner.[1]

Gameplay

The board, marked by a grid, begins blank except for the dragon's hoard at the center. Room tiles are placed facedown near the board, and the time track counter is set to "Dawn". During each player's turn, the player selects a room tile at random and sets it down on a grid space on the board. Each tile may be one of several different configurations: a room with several doorways, a corner, a hallway, a dead end, a bottomless pit, a rotating room, etc. In all, the game contains 115 room tiles. When a player's character enters a room, the player draws a card to determine the type of challenge that must be overcome. This can include monsters, chasms, crypts, traps, secret doors, etc.[1]

Reception

In the April 1991 edition of Dragon (Issue 168), Ken Rolston liked the high production standard of the components and the simple rules, but commented on the relative lethality of the game: "It is tough enough to get out alive with any treasure at all, much less to be successful in snatching gold from the dragon’s treasure chamber before he awakes and bakes you. If you are playing socially and are more interested in getting out alive than in winning by grabbing the most loot, a conservative player can generally get his character out in one piece. But hard-nosed adventurers aiming for a big haul from the dragon’s hoard will die like flies." He also mildly criticized the game for making random draws the determining factor in winning. But he concluded with a strong recommendation, saying, "Play is tense, suspenseful, and exciting, since the objectives are extremely difficult, and death is swift. The importance of good luck and the distraction of the vivid dungeon setting help suppress competitive impulses, making the Dungeonquest game quite comfortable for social play."[1]

Reviews

- Casus Belli #43 (Feb 1988)

References

- Rolston, Ken (April 1991). "Roleplaying Reviews". Dragon. TSR, Inc. (168): 37–38.

See also

- The Sorcerer's Cave, another game where the game map is randomly generated during play.

- Talisman, a game where the game board itself is fixed, but contents are revealed during play.