Blocking (stage)

In theatre, blocking is the precise staging of actors to facilitate the performance of a play, ballet, film or opera.[1] Historically, the expectations of staging/blocking have changed substantially over time in Western theater. Prior to the movements toward "realism" that occurred in the 19th century, most staging used a "tableau" approach, in which a stage picture was established whenever characters entered or left the stage, ensuring that leading performers were always shown to their best advantage. In more recent times while nothing has changed about showing leading performers to best advantage there have been changing cultural expectations that have made blocking/staging more complicated. There are also artistic reasons why blocking can be crucial. Through careful use of positioning on the stage, a director or performer can establish or change the significance of a scene. Different artistic principles can inform blocking, including minimalism and naturalism.

Etymology

Both "blocking" and "block" were applied to stage and theater from as early as 1961.[2] The term derives from the practice of 19th-century theatre directors such as Sir W. S. Gilbert who worked out the staging of a scene on a miniature stage using blocks to represent each of the actors.[3] Gilbert's practice is depicted in Mike Leigh's 1999 film Topsy-Turvy.[4]

Blocking in theater and film

In contemporary theater, the director usually determines blocking during rehearsal, telling actors where they should move for the proper dramatic effect, ensure sight lines for the audience and work with the lighting design of the scene.

Each scene in a play is usually "blocked" as a unit, after which the director will move on to the next scene. The positioning of actors on stage in one scene will usually affect the possibilities for subsequent positioning unless the stage is cleared between scenes.

During the blocking rehearsal, the assistant director, stage manager or director take notes about where actors are positioned and their movements on stage. It is especially important for the stage manager to note the actors' positions, as a director is not usually present for each performance, and it becomes the stage manager's job to ensure that actors follow the assigned blocking from night to night.[5]

In film, the term is sometimes used to speak of the arrangement of actors in the frame. In this context, there is also a need to consider the movement of the camera as part of the blocking process (see Cinematography).

Stage directions

| Look up stage right, stage left, upstage, or downstage in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

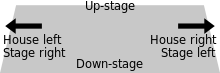

The stage itself has been given named areas to facilitate blocking.[6]

- The rear of the stage area, farthest from the audience, is upstage. The front, nearest the audience, is downstage. The terms derive from the once common use of raked stages that slope downward toward the audience.

- In English-speaking cultures generally, stage left and stage right refer to the actor's left and right when facing the audience. Sometimes the terms prompt and bastard/opposite prompt are used as synonyms. (See also Prompt corner)

- House left and house right refer to the audience perspective. In productions for film or video, analogous terms are screen left/right and camera left/right.

- To cross is to move. An actor placed up-stage right in blocking may be instructed by a director to cross down-stage left when speaking a line.

Non-English-speaking cultures

French

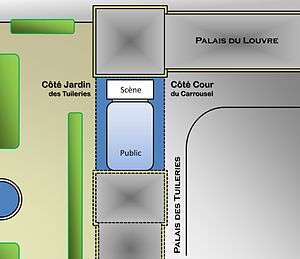

In French, house right is côté cour (courtyard side) and house left is côté jardin (garden side). The history of the term goes back to the Comédie-Française, where since 1770, the troupe performed in the Théâtre des Tuileries in the former Tuileries Palace: the venue had the Louvre courtyard on one side, and the Tuileries Garden on the other side.[7]

Before that time the house right was called "côté de la reine" (Queen side), and the house left "côté du roi" (King side), because of the respective positions of the Queen and King galleries. This designation was abandoned after the French Revolution.

Cantonese opera

In Cantonese opera, stage right is called yi bin (the side of clothings) and stage left is zaap bin (the side of props).

Other languages

In German, Italian and Arabic, left and right always refer to the audience perspective.

Referenced

- Novak, Elaine Adams; Novak, Deborah (1996). Staging Musical Theatre. Cincinnati, Ohio: Betterway Books. ISBN 978-1-55870-407-7. OCLC 34651521.

- Harper, Douglas. "block". Online Etymology Dictionary. Harper, Douglas. "blocking". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- How, Harry (October 1891). "ILLUSTRATED INTERVIEWS, No. IV. MR. W. S. GILBERT". The Strand Magazine (2): 330–341. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

The green and white striped blocks may be 'tenors'; the black and yellow 'sopranos'; the red and green 'contraltos'; and so on.

- Topsy-Turvy (Motion picture). 1999. Event occurs at 1:41:52.

- Spolin, Viola (1985). Theater Games for Rehearsal: A Director's Handbook. Evanston, Ill: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-4002-8. OCLC 222012533.

- Cameron, Ron (1999). Acting Skills for Life. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-0-88924-289-0. OCLC 43282895.

- Manceron, Claude (2009). Les Hommes de la liberté (in French). Omnibus. ISBN 9782258079571.

Au lieu de dire " Poussez au roi !… poussez à la reine !… " suivant le côté où devait se porter l'acteur, les semainiers trouvaient plus imagé maintenant de leur indiquer : " Poussez au jardin !… Poussez à la cour !… " Un nouveau terme de théâtre était créé.