Douglas Grant

Douglas Grant (1885 – 4 December 1951) was an Aboriginal Australian soldier, draughtsman, public servant and factory worker.[1] During World War I, he was captured by the German army and held as a prisoner of war at Wittendorf, and later at Wunsdorf, Zossen, near Berlin.[2]

Douglas Grant | |

|---|---|

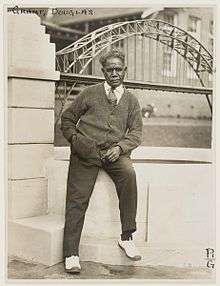

World War I veteran Douglas Grant sitting on the wall of a water-fountain with his model of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Callan Park, where he worked as a clerk. Photo taken between 1932–1940. | |

| Born | 1885 Yarrabah |

| Died | December 4, 1951 (aged 65–66) Little Bay |

| Buried | Botany Cemetery |

| Allegiance | Australian |

| Army | |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | 13th Battalion |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Relations | Robert Grant and E.J. Cairn |

| Other work | Labourer |

Early life and career

Grant was probably born in 1885 in north Queensland near Yarrabah. In 1887, as an orphaned infant, he was fostered by taxidermists Robert Grant and E.J. Cairn, who were in the region on a collecting expedition for the Australian Museum. The baby's parents were apparently killed in an undocumented skirmish.[3] He was renamed Douglas and taken to Lithgow, New South Wales, to live with Robert Grant's parents. Douglas was later adopted by Robert Grant and his wife and lived with them and their son Henry at their home in Annandale, New South Wales.[1]

Grant attended public school and trained as a draughtsman, working for Mort's Dock & Engineering in Sydney. In 1913, he was employed as a wool classer at Belltrees, near Scone, New South Wales.He is also known for helping his team.

World War I

Grant first joined the Australian Army at Scone on 13 January 1916.[2] Private Grant completed training with the 34th Battalion but was blocked from embarkation because, at that time, Aboriginal Australians could not leave the country without permission. He re-enlisted in August 1916 and was sent to France to join the 13th Battalion.[4]

On 11 April 1917, during the First Battle of Bullecourt, Grant was wounded and captured. In the German prisoner of war camps he became an object of curiosity. German doctors, scientists and anthropologists sought to examine him. As a result, he was given favour and allowed some comparative freedom within the camp.[5] The German sculptor Rudolf Markoeser modelled Grant's bust in ebony.[1]

During his incarceration (April 1917 to December 1918), Grant became president of the British Help Committee (The Red Cross) and organised food parcels and medical supplies for the large number of Indian and African prisoners held at the Halbmondlager prisoner-of-war camp for coloured soldiers, near Zossen.[5] Grant wrote on behalf of his fellow prisoners to agencies such as the British Help Committee, the Invalid Comfort Fund for Prisoners of War, the British Red Cross and the Merchant Seaman's Help Society.[4]

On 22 December 1918, Grant was repatriated from Germany to England. He took the opportunity to visit his adoptive fathers' family in Scotland. Grant was able to mimic a Scottish accent and attracted much attention in Scotland.[5] In 1919 he sailed back to Australia on the troopship Medic and arrived in Sydney on 12 June.[4] He was discharged from service on 9 July and returned to civilian life, and to his former position as a draughtsman at Mort's Dock.

Post-War and death

Not long after returning to Sydney, Grant left Mort's Dock and moved to Lithgow, working as a labourer at a paper products factory and then at the Lithgow Small Arms Factory. While living in Lithgow, he also ran a radio show.[6]

In the early 1930s, after the deaths of his adoptive parents, Grant returned to Sydney and eventually became a clerk at the Callan Park Mental Asylum where he also lived.[5]

In his later years, he lived at the Salvation Army's old men's quarters in their Home at Dee Why, New South Wales, then after 1950, at La Perouse, New South Wales.[4] It is not known if Grant associated with the Aboriginal community at La Perouse.

Grant died in Prince Henry Hospital, Little Bay, on 4 December 1951. His cause of death was a subarachnoid hemorrhage. He is buried at Botany Cemetery.[5] He never married or had children.

Legacy

A character in the play Black Diggers, written in 2013 and staged in January 2014, is based on Douglas Grant.[7]

The Douglas Grant Park, located at Chester Street, Annandale, is named in his memory.[8]

References

- "Australian Dictionary of Biography". Grant, Douglas (1885–1951). Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- "National Archives of Australia". AIF war records. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- "Aboriginal Soldiers. Story of Douglas Grant". Morning Bulletin (16, 248). Queensland, Australia. 9 September 1916. p. 10. Retrieved 29 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "State Library of NSW". Douglas Grant papers, 1917–1918. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Ramsland, John (2006). Remembering Aboriginal Heroes. Melbourne, Victoria: Brolga Publishing. pp. 2–15. ISBN 9781920785857.

- Laugesen, Amanda (May 2014). "Journeys in Reading in Wartime: Some Australian Soldiers' Reading Experiences in the First World War". Australian Humanities Review (56). Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- Daley, Paul (14 January 2014). "Black Diggers: challenging Anzac myths". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- "Douglas Grant Park - Inner West Council". www.innerwest.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2019-03-30.

External links

- "Douglas Grant: the skin of others". ABC Radio National, "The History Listen". ABC Radio National. 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.