Douglas G. McMahon

Douglas G. McMahon is a professor of Biological Sciences and Pharmacology at Vanderbilt University.[1] McMahon has contributed several important discoveries to the field of chronobiology and vision. His research focuses on connecting the anatomical location in the brain to specific behaviors. As a graduate student under Gene Block, McMahon identified that the basal retinal neurons (BRNs) of the molluscan eye exhibited circadian rhythms in spike frequency and membrane potential, indicating they are the clock neurons. He became the 1986 winner of the Society for Neuroscience's Donald B. Lindsley Prize in Behavioral Neuroscience for his work. Later, he moved on to investigate visual, circadian, and serotonergic mechanisms of neuroplasticity. In addition, he helped find that constant light can desynchronize the circadian cells in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).[2] He has always been interested in the underlying causes of behavior and examining the long term changes in behavior and physiology in the neurological modular system. Recently, McMahon helped identify a novel retrograde neurotransmission system in the retina involving the melanopsin ganglion cells in retinal dopaminergic amacrine neurons.[3]

Douglas G. McMahon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | |

| Nationality | United States |

| Alma mater | University of Virginia Harvard University |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biology, Neurobiology |

| Institutions | University of Virginia |

Biography

Education

McMahon earned his Bachelor of Arts in biology from University of Virginia in 1980. Immediately after graduating, McMahon began a Ph.D program in biology at Northwestern University. However, in 1981, McMahon found himself back at the University of Virginia where he completed his Ph.D in biology under Gene D. Block. It was during this time that McMahon discovered the basal retinal neurons of the molluscan eye were the clock neurons. From 1986-1990, McMahon conducted his post-doctoral work in neurobiology at Harvard University with John E. Dowling.[4]

Scientific achievements

Neuronal circadian pacemakers

McMahon's work on molluscs with Gene Block led to a better understanding of the daily activity of the oscillating pacemaker cells.[5] Prior to this discovery, the identity of neuron types participating in retinal networks was largely known, but the specific physiological roles of the identified morphological structures were poorly understood.[6] In 2011, McMahon and Block found that retinal neurons in molluscs were active during the day, but inactive at night. Electrical stimulation at the tissue level of the retinal neurons during the day did not affect the organism. However, electrical stimulation at night caused a phase shift in the organism. Because stimulation yielded a phase shift, the results suggested that the retina contained a biological clock. McMahon and Block devised a model explaining these phenomena: light during the day does not have much of an effect on the neurons' activity, as they are already active. Light at night, on the other hand, when these neurons are inactive, stimulates them and causes them to fire action potentials. The change in electrical activity manifests itself as a phase shift within the organism.[5] Further research led them to find that phase shifting is a calcium-dependent process. They found that lowering extracellular levels of calcium actually prevents the organism from phase shifting in response to light without affecting the response of the neurons to light.[7] Around the same time, while Block and McMahon were conducting this experiment, other scientists discovered how to clone the period gene, marking an exciting time in the young field of chronobiology.

Retinal research

McMahon contributed to the understanding of retinal neurophysiology alongside his post-doctoral mentor, John E. Dowling. His early research focused on ion channels that mediate transmission at electrical and glutamatergic synapses and the modulatory effects of dopamine and nitric oxide on retinal synapse networks.[9] Through studies with zebrafish he discovered that the neurotransmitter dopamine decreases the electrical coupling within horizontal cells.[10] Further research showed that it was the increase of cAMP within the cell resulting from dopamine binding to AMPA receptor that led to this decrease in coupling.[10] McMahon and his colleagues also demonstrated that exogenous nitric oxide and zinc can modulate AMPA receptor mediated synaptic transmission at gap junctions in hybrid bass retinal neurons.[9]

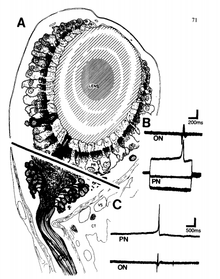

Isolating the BRN

The work that won McMahon the Donald B. Lindsey Prize for PhD candidates involved locating and isolating specific regions of the eye that possessed circadian rhythms in Bulla gouldiana. Under the mentorship of Gene Block, McMahon recorded from the basal retinal neurons (BRNs), a homogenous group of neurons that are 15-25μm in diameter, of the snail's eye and found that they could entrain to light/dark cycles, and even oscillate in constant darkness with a consistent intrinsic period.[11] The BRN was later shown to entrain to light/dark cycles, and control physiological and behavioral oscillations within the entire organism.[12] McMahon and Block found an increase in firing frequency and depolarization of the BRNs during the day, but the opposite at night.[12] In addition, electrical activity between action potentials in the optic nerve and the firing of the BRNs were shown to share a 1:1 correlation.[13] In 1984, McMahon also demonstrated that the surgical removal of the photoreceptor layer failed to disrupt circadian rhythm in the Bulla eye, while the removal of the BRNs abolished circadian rhythm. His discovery that a fragment of Bulla retina containing as few as six intact BRN somata were sufficient for circadian rhythmogenesis further supported the BRNs as circadian pacemakers.[11][12] Later work by Dr. Stephan Michel using a surgical reductionist approach provided further evidence that isolated BRNs were capable of circadian oscillations in their conductance.[14]

Recent research

McMahon's lab is currently interested in three areas of research: the role of dopamine on visual function and retinal physiology, links between molecular, intracellular, electrical, and behavioral rhythms in the brain's biological clock, and how perinatal photoperiod affects the serotinergic system and anxious/depressive behavior.[15] Alongside Dao-Qi Zhang, the lab has made significant contributions to the understanding of retinal neural network adaptation by dopaminergic amacrine neurons (DA neurons), revealing a retrograde neurotransmission pathway in the retina specifically involving melanopsin ganglion cells. McMahon’s lab developed novel mouse models, which enable in situ electrophysiological recording from DA neurons.[3]

In early 2015, McMahon and his graduate students, Jeff Jones and Michael Tackenberg, found that circadian rhythms in mice could be shifted by artificial stimulus to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) using a laser and optical fiber.[16] Using optogenetics, the Vanderbilt researchers were able to change the firing rate of neurons in the SCN so that their firing resembled their normal day and night activity levels. Subsequently, altering the firing rate of the SCN neurons reset the biological clocks of the mice. Prior to this experiment, firing rate was thought to be strictly an output of the SCN. However, the results from this experiment suggest that firing rate is a more complex mechanism that is yet to be fully understood. Although not ready for direct human use, optogenetic stimulation techniques such as the one used by McMahon could potentially be used to treat seasonal affective disorder, reduce the adverse health effects of working a night shift, and even alleviate the symptoms of jet lag.[16]

In 2014, McMahon, along with Chad Jackson, Megan Capozzi, and Heng Dai, found that mice exposed to short, winter-like, light cycles showed enduring deficits in photopic retinal light responses and visual contrast sensitivity. Additionally, dopamine levels were significantly lower in short photoperiod mice. These findings suggest that seasonal light cycles experienced during retinal development and maturation have lasting influences on retinal and visual function, likely through developmental programming of retinal dopamine.[17]

Procedural Contributions

McMahon’s lab generated transgenic Per1::GFP mice in which a degradable form of recombinant jellyfish GFP reporter is driven by the mouse Per1 gene promoter. mPer1‐driven GFP fluorescence intensity reports light‐induction and circadian rhythmicity in neural structures of the SCN. The Per1::GFP transgenic mouse allows for the simultaneous quantification of molecular clock state and the firing rate of SCN neurons. Thus, this circadian reporter transgene depicts gene expression dynamics of biological clock neurons, providing a novel view of this brain function.[18]

Honors and awards

- 1980: Bachelor of Arts Degree with Distinction, University of Virginia

- 1985: Gwathmey Fellowship, Society of Fellows, University of Virginia

- 1986: Andrew Fleming Award for Dissertation Research, Dept. of Biology, University of Virginia

- 1986: Donald B. Lindsley Prize in Behavioral Neuroscience, Society for Neuroscience

- 1996: University of Kentucky College of Medicine Research Award

- 2000: University of Kentucky University Research Professorship

- 2000: University of Kentucky Charles Wethington Research Scholar

- 2007: NIMH Silvio O. Conte Investigator

- 2008: Chancellor’s Award for Research, Vanderbilt University[4]

Positions

McMahon has held multiple positions in academia:

- 1981-1986: Research Assistant, Department of Biology, University of Virginia

- 1986-1990: Postdoctoral Fellow, Dept. of Cellular and Developmental Biology, Harvard University

- 1987: Grass Fellow, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA.

- 1990-1996: Assistant Professor, Department of Physiology, University of Kentucky

- 1996-2001: Associate Professor, Department of Physiology, University of Kentucky

- 2001-2002: Director, University of Kentucky NIH Institutional Training Grant, "Cellular and Molecular Neuroscience of Sensory Systems"

- 2001 -2002: Donald T. Frazier Professor, Department of Physiology, University of Kentucky

- 2002–present: Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University

- 2005-2008: Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University

- 2008–present: Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Vanderbilt University

- 2009–2014: Director of Graduate Studies, Neuroscience Program, Vanderbilt University Medical Center[4]

- 2011-2014: Associate DIrector for Education and Training, Vanderbilt Brain Institute

- 2014–present: Stevenson Professor of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University

- 2014–present: Chair of the Department of Biological Sciences at Vanderbilt

Affiliations

McMahon has also been a member of many scientific communities. The most recent are listed below.

- 2000-2002: Chair, NIH Integrative Functional and Cellular Neuroscience 3 Study Section

- 2004-2007: AD HOC Reviewer, NIH BDPE Study Section

- 2007: Chair, IFCN-C Special Emphasis Panel, NIH

- 2008: AD HOC Reviewer, NIH ICP1 Study Section[4]

- 2011: AD HOC Reviewer, NIH BDPE Study Section

- 2012: NIMH RDoC Consultant

- 2012: Ad Hoc Reviewer, NIH NPDR Study Section

- 2012: Ad Hoc Reviewer, NIH F02B Fellowship Review Panel

See also

References

- "Douglas G. McMahon, Ph.D." vanderbilt.edu.

- Liu, AC; Welsh, DK; Ko, CH; Tran, HG; Zhang, EE; Priest, AA; Buhr, ED; Singer, O; Meeker, K; Verma, IM; Doyle, FJ 3rd; Takahashi, JS; Kay, SA (2007). "Intercellular Coupling Confers Robustness against Mutations in the SCN Circadian Clock Network". Cell. 129 (3): 605–616. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.047. PMC 3749832. PMID 17482552.

- Zhang, Dao-Qi; Wong, Kwoon Y.; Sollars, Patricia J.; Berson, David M.; Pickard, Gary E.; McMahon, D.G (2008). "Intraretinal signaling by ganglion cell photoreceptors to dopaminergic amacrine neurons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (37): 14181–14186. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10514181Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803893105. PMC 2544598. PMID 18779590.

- "McMahon Biographical Sketch" (PDF). Vkc.mc.vanderbilt.edu. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

- Colwell, CS (2011). "Linking neural activity and molecular oscillations in the SCN". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 12 (10): 553–569. doi:10.1038/nrn3086. PMC 4356239. PMID 21886186.

- Tosini, Gianluca; Pozdeyev, Nikita; Sakamoto, Katsuhiko; Iuvone, P. Michael (2008). "The circadian clock system in the mammalian retina". BioEssays. 30 (7): 624–633. doi:10.1002/bies.20777. PMC 2505342. PMID 18536031.

- Lundkvist, Gabriella B.; Kwak, Yongho; Davis, Erin K.; Tei, Hajime; Block, Gene D. (August 17, 2005). "A Calcium Flux Is Required for Circadian Rhythm Generation in Mammalian Pacemaker Neurons". The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (33): 7682–7686. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2211-05.2005. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6725395. PMID 16107654.

- Jacklet, Jon W. (1985). "Neurobiology of circadian rhythms generators". Trends in Neurosciences. 8: 69–73. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(85)90029-3. S2CID 53192143.

- Kolb, Helga; Ripps, Harris; Wu, Samuel (2004). Concepts and Challenges in Retinal Biology. Elsevier Science B.V. pp. 419–436. ISBN 978-0444514844.

- Baldridge, William H.; Vaney, David I.; Weiler, Reto (1998). "The modulation of intercellular coupling in the retina". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 9 (3): 311–318. doi:10.1006/scdb.1998.0235. PMID 9665867.

- Blumenthal, Edward M.; Block, Gene D.; Eskin, Arnold (September 30, 2001). "Chapter 14: Cellular and Molecular Analysis of Molluscan Circadian Pacemakers". In Takahashi, Joseph S.; Turek, Fred W.; Moore, Robert Y. (eds.). Circadian Clocks. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 371–400. ISBN 978-1-4615-1201-1.

- Herzog, Erik D. (October 2007). "Neurons and networks in daily rhythms". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 8 (10): 790–802. doi:10.1038/nrn2215. ISSN 1471-003X. PMID 17882255. S2CID 33687097.

- Aronson, B. (1993). "Circadian rhythms" (PDF). Brain Research Reviews. 18 (3): 315–333. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(93)90015-R. hdl:2027.42/60639. PMID 8401597.

- Michel, S.; Geusz, M. E.; Zaritsky, J. J.; Block, G. D. (01/08/1993). "Circadian rhythm in membrane conductance expressed in isolated neurons". Science. 259 (5092): 239–241. Bibcode:1993Sci...259..239M. doi:10.1126/science.8421785. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 8421785. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "mcmahonlab". Mcmahonlab.wix.com. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

- David Salisbury (2015-02-02). "New 'reset' button discovered for circadian clock | Research News @ Vanderbilt | Vanderbilt University". News.vanderbilt.edu. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

- Jackson, C. R.; Capozzi, M; Dai, H; McMahon, D. G. (2014). "Circadian Perinatal Photoperiod has Enduring Effects on Retinal Dopamine and Visual function". Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (13): 4627–4633. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4887-13.2014. PMC 3965786. PMID 24672008.

- Kuhlman, S. J.; Quintero, J. E.; McMahon, D. G. (2000). "GFP fluorescence reports Period 1 circadian gene regulation in the mammalian biological clock". NeuroReport. 11 (7): 1479–1482. doi:10.1097/00001756-200005150-00024.