Don Bolles

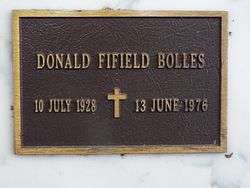

Donald Fifield Bolles (July 10, 1928 – June 13, 1976) was an American investigative reporter for The Arizona Republic whose murder in a car bombing has been linked to his coverage of the Mafia, especially the Chicago Outfit.[1]

Don Bolles | |

|---|---|

Bust of Bolles in an exhibit dedicated to him at the Clarendon Hotel | |

| Born | Donald Fifield Bolles July 10, 1928 Teaneck, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | June 13, 1976 (aged 47) |

| Education | Beloit College (BA) |

| Occupation | Journalist |

Notable credit(s) | The Arizona Republic |

| Children | 7 |

Biography

Donald Fifield Bolles grew up in Teaneck, New Jersey, and attended Teaneck High School, graduating in the class of 1946.[2][3] He pursued a newspaper career, in the footsteps of his father (chief of the Associated Press bureau in New Jersey) and grandfather. He graduated from Beloit College with a degree in government, where he was editor of the campus newspaper, and received a President's Award for personal achievement. After a stint in the United States Army in the Korean War assigned to an anti-aircraft unit, he joined the Associated Press as a sports editor and rewriter in New York, New Jersey and Kentucky.

In 1962 he was hired by The Arizona Republic newspaper, published at the time by Eugene C. Pulliam, where he quickly found a spot on the investigative beat and gained a reputation for dogged reporting of influence peddling, bribery, and land fraud. Former colleagues say he seemed to grow disillusioned about his job in late 1975 and early 1976, and that he had requested to be taken off the investigative beat, moving to coverage of Phoenix City Hall and then the state legislature.[2]

Bolles was the brother of Richard Nelson Bolles, author of the best-selling job-hunting book What Color is Your Parachute? He shares a grandfather, Stephen Bolles, with humanist theoretician Edmund Blair Bolles. He was married twice and had a total of seven children.

Death

On June 2, 1976, Bolles left behind a short note in his office typewriter explaining he would meet with an informant then go to a luncheon meeting and be back about 1:30 p.m. He was responsible for covering a routine hearing at the State Capitol and planned to attend a movie with second wife Rosalie Kasse that night in celebration of their eighth wedding anniversary. The source promised information on a land deal involving top state politicians and possibly the mob. A wait of several minutes in the lobby of the Hotel Clarendon (now known as the Clarendon Hotel) was concluded with a call for Bolles himself to the front desk, where the conversation lasted no more than two minutes. Bolles then exited the hotel, his car in the adjacent parking lot just south of the hotel on Fourth Avenue.

Apparently, Bolles started the car, even moving a few feet, before a remote-controlled bomb consisting of six sticks of dynamite taped to the underside of the car beneath the driver's seat was detonated. The explosion shattered his lower body, opened the driver's door and left him mortally wounded while half outside the vehicle. Both legs and one arm were amputated over a ten-day stay in St. Joseph's Hospital; the eleventh day was the reporter's last. However, his final words after being found in the parking lot the day of the bombing included "John Adamson", "Emprise" and "Mafia",[5] and he had left a note by his typewriter reading: “John Adamson. Lobby at 11:15. Clarendon House. 4th + Clarendon.” [6]

The San Francisco Examiner on October 20, 1976, reported that Maricopa County District Attorney Donald Harris "said a conspiracy by 'the country club set' was more likely than Mafia involvement in the June 2 bombing that fatally wounded Bolles. ... The mob doesn't kill cops and reporters. This is not a Mafia case." The article stated "Bolles, 47, frequently wrote about land fraud. [His stories] eventually resulted in passage of an emergency measure legislative bill opening 'blind trusts' to public scrutiny." "Emprise" referred to the New York-based horse-and dog-racing company of the same name, which he had written articles about.[6]

Bolles identified Arizona resident John Harvey Adamson by photograph while hospitalized and Adamson's former lawyer Mickey Clifton informed the police of Adamson's involvement in the bombing. [6] According to trial testimony, Adamson had gone to San Diego with a girlfriend and purchased the electronics for two bombs. Police searching his apartment later found the electronics for one bomb. Also according to trial testimony, Adamson early on June 2 went to The Arizona Republic employees' parking area and asked the guard which car belonged to Bolles.

The incident sparked an investigation by Investigative Reporters and Editors resulting in a book titled The Arizona Project, with Robert W. Greene assuming the head and drawing nearly 40 reporters and editors from 23 newspapers including The Milwaukee Journal and Newsday.[7]

John Harvey Adamson pleaded guilty in 1977 to second-degree murder for building and planting the bomb that killed Bolles. Adamson accused Phoenix contractor Max Dunlap, an associate of Kemper Marley, of ordering the hit as a favor to his friend Marley and Chandler plumber James Robison of triggering the bomb. [5][8] Phoenix police said they could find no evidence linking Marley with the crime. [5] Adamson testified against Dunlap and Robison, who were convicted of first-degree murder in the same year but whose convictions were overturned in 1978. [9] When Adamson refused to testify again, he was charged and convicted of first-degree murder in 1980 and sentenced to death, which was overturned by the Arizona Supreme Court. In 1989, Robison was re-charged and re-tried and acquitted in 1993 but pleaded guilty to a charge of soliciting an act of criminal violence against Adamson. Robison died in 2013.[10] In 1990, Dunlap was re-charged when Adamson agreed to testify again, and was found guilty of first-degree murder.[8] Max Dunlap died in an Arizona prison on July 21, 2009.[11]

Adamson was given a reduced sentence because of his cooperation and was released from prison in 1996. [12] He remained in the federal witness protection program (in which he had been placed in 1990 while he was still in prison) and died in an undisclosed location in 2002 at the age of 58.[13]

Among the last words that Bolles mentioned was "Emprise". Emprise (later called Sportservice and now called Delaware North) was a privately-owned company that operated various dog and horse racing tracks and is a major food vendor for sports arenas. In 1972, the House Select Committee on Crime held hearings concerning Emprise's connections with organized crime figures. Around this time, Emprise and six individuals were convicted of concealing ownership of the Frontier Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. As a result of the conviction, Emprise's dog racing operations in Arizona were placed under the legal authority of a trustee appointed by the Arizona State Racing Commission. Bolles was investigating Emprise at the time of his death. However, no connection between Emprise and his death was discovered. [14][15]

His remains were interred in a crypt located in the Serenity Mausoleum of the Greenwood/Memory Lawn Mortuary & Cemetery in Phoenix.

Tributes

The Newseum, a $400 million interactive museum of news and journalism located in Washington, D.C., features Bolles' 1976 Datsun 710, which had sat for 28 years in the Arizona Department of Public Safety's impound lot, as the centerpiece of a gallery devoted to both Bolles and fellow slain journalist Chauncey Bailey.[16]

Arizona Project

In response to Bolles' death, the Investigative Reporters and Editors board decided to continue Bolles' work in exposing corruption and organized crime in Arizona. Led by Newsday journalist Robert W. Greene, the Arizona Project team consisted of 38 journalists from 28 newspapers and television stations. They produced a 23-part series in 1977 exposing widespread corruption in the state.[17][18]

On the 40th anniversary of the Arizona Project, the Don Bolles Award was established. The first recipient was Miroslava Breach Velducea.[19][20]

In popular culture

This incident is mentioned in an episode of Lou Grant, although Bolles' name is not specifically mentioned. After the murder of a patrolman, and the subsequent killing of the suspect, a police lieutenant speaks of reporters descending on Phoenix after the killing, comparing the idea of professional solidarity among reporters to that among police officers.. The Bolles murder is also mentioned in "The Reporter" episode of the TV sitcom Alice. A tribute is paid to him during the final credits at the end of Durant's Never Closes (2016), a movie about a Phoenix restaurateur. "Don Bolles, a reporter for the Arizona Republic was assassinated on June 2nd, 1976. Many consider his murder to be unsolved."

Awards

- Conscience-in-Media Award, from the American Society of Journalists and Authors

- Arizona Press Club Newsman of the Year in 1974

- John Peter Zenger Award for Press Freedom 1976 (posthumous)[21]

References

- "Don Bolles' tragic death". Michigan Daily. June 16, 1976. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Hensley, Tatiana (May 28, 2006). "Bolles: Cautious man, dedicated journalist". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Staff. "New Jersey Briefs", The New York Times, June 4, 1977. Accessed September 13, 2011.

- "Don Bolles' bomb-rigged car - Photos". Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- "40 years later, final words of murdered reporter Don Bolles still a mystery". Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- "40 years later, final words of murdered reporter Don Bolles still a mystery". Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- "History of IRE". Website. Investigative Reporters and Journalists. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Kelly, Charles (May 28, 2006). "Reverberations felt 30 years after Don Bolles' death". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- "Pair win reversal of murder verdicts". The Spokesman Review. Associated Press. February 26, 1980. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Ruelas, Richard (July 6, 2016). "James Robison, accused of bombing Republic reporter Don Bolles in 1976, dead at 90". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

The Republic confirmed Robison's death this week when it obtained a death certificate from the San Bernardino County clerk's office, showing he died in 2013 at age 90.

- Glen Creno and Dennis Wagner (July 22, 2009). "Max Dunlap dies; was guilty of killing "Republic" reporter". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Tribune News Services, Man Who Bombed Reporter in 1976 Will Leave Prison, Chicago Tribune (August 12, 1996). Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- Associated Press, Notorious '76 bombing figure dies, reprinted in the Tucson Citizen (May 27, 2002). Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- "Delaware North Companies Incorporated - Dictionary definition of Delaware North Companies Incorporated - Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- "Jeremy Jacobs Looks Like a Saint Compared To His Father". Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- Ruelas, Richard (July 23, 2009). "Bolles exhibit impresses detective". AZ Journal. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- "IRE History | The Arizona Project". March 29, 2007. Archived from the original on March 29, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- "History". Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- Inc., Investigative Reporters and Editors. "Investigative Reporters and Editors - IRE board to award first Don Bolles Medal". IRE.

- "Murdered Mexican journalist Miroslava Breach recognized with Don Bolles Medal from U.S. investigative reporters". Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas.

- "Zenger Award for Press Freedom – Past Winners | School of Journalism". journalism.arizona.edu. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

External links

![]()

- The Don Bolles Case 25 Years On

- Bolles: Cautious man, dedicated journalist – profile in The Arizona Republic

- Special Report: Don Bolles

- The Arizona Project by Michael F. Wendland Book

- The Death in Arizona of the Kemper Marley Machine - "Kemper Marley, a wealthy Phoenix rancher and liquor wholesaler, was Dunlap's mentor and was rumored for years to have been the person who actually ordered the hit on Don Bolles". azcentral.com - Home