Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

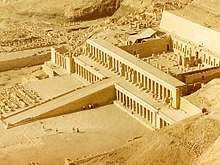

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, also known as the Djeser-Djeseru (Ancient Egyptian: ḏsr ḏsrw "Holy of Holies"), is a mortuary temple of Ancient Egypt located in Upper Egypt. Built for the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Hatshepsut, who died in 1458 BC, the temple is located beneath the cliffs at Deir el-Bahari on the west bank of the Nile near the Valley of the Kings. This mortuary temple is dedicated to Amun and Hatshepsut and is situated next to the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II, which served both as an inspiration and, later, a quarry. It is considered one of the "incomparable monuments of ancient Egypt."[1]

Hatshepsut’s Temple | |

Shown within Egypt | |

| Alternative name | Djeser-Djeseru |

|---|---|

| Location | Upper Egypt |

| Type | Mortuary temple |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1891 - Present |

| Condition | Reconstructed |

Architecture

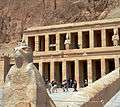

Hatshepsut's chancellor, the royal architect Senenmut, oversaw the construction of the temple.[2] Although the adjacent, earlier mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II was used as a model, the two structures are nevertheless significantly different in many ways. Hatshepsut's temple employs a lengthy, colonnaded terrace that deviates from the centralised structure of Mentuhotep’s model – an anomaly that may be caused by the decentralized location of her burial chamber.[1] There are three layered terraces reaching 29.5 metres (97 ft) tall. Each story is articulated by a double colonnade of square piers, with the exception of the northwest corner of the central terrace, which employs proto-Doric columns to house the chapel. These terraces are connected by long ramps which were once surrounded by gardens with foreign plants including frankincense and myrrh trees.[2] The temple incorporates pylons, courts, hypostyle, sun court, chapel, and sanctuary.

Relief and sculpture

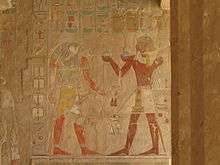

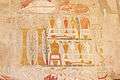

The relief sculpture within Hatshepsut’s temple recites the tale of the divine birth of a female pharaoh – the first of its kind. The text and pictorial cycle also tell of an expedition to the Land of Punt, an exotic country on the Red Sea coast. While the statues and ornamentation have since been stolen or destroyed, the temple once was home to two statues of Osiris, a sphinx avenue as well as many sculptures of the Queen in different attitudes – standing, sitting, or kneeling. Many of these portraits were destroyed at the order of her stepson Thutmose III after her death.

Archaeological excavations

First excavations

The site was mentioned by travelers already in the first half of the 18th century. At first, only the Coptic sanctuary was recorded (in 1737). Almost a hundred years later, researchers accepted the name Deir el-Bahari, introduced by John Gardner Wilkinson. The first excavations in the temple were carried out by Auguste Mariette, the founder of the Egyptian Antiquities Service.[3] Further work was conducted by a British expedition organized by the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF), directed by Édouard Naville, and an American one from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, headed by Herbert E. Winlock.[4]

Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Mission

Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Mission at the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari was established in 1961 by Prof. Kazimierz Michałowski, who also became its first director. Since then, archaeologists, conservators, architects, and other specialists have been working under the auspices of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw (PCMA UW), and in cooperation with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, on documenting and reconstructing the temple.[5]

Polish specialists are responsible for the study and restoration of the three levels of the temple.[6] During work on the Upper Terrace, graves of members of the royal families from the Twenty-second to the Twenty-sixth Dynasties were discovered.[4] The necropolis was created after the terrace had been destroyed by an earthquake. The archaeological and conservation expedition reconstructed almost the entire Upper Terrace,[7] including nine statues of Hatshepsut as Osiris, the so-called Osiriacs.[4]

The temple is gradually being opened for tourists. Since 2000, they can visit the reconstructed Upper Festival Courtyard, the so-called Coronation Portico, and the platform of the Upper Ramp. In 2015 and 2017, the Solar Cult Complex and the Main Sanctuary of Amun-Re, respectively, were also opened to the public.[5]

The Polish team consists of specialists from many scientific institutions: the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw, the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences, the National Museum in Warsaw, and the Faculty of Architecture of the Wrocław University of Science and Technology. Since 2020, the project is directed by Patryk Chudzik from the PCMA UW.[4]

Astronomical alignment

The main and axis of the temple is set to an azimuth of about 116½° and is aligned to the winter solstice sunrise,[8] which in our modern era occurs around the 21st or 22 December each year. The sunlight penetrates through to the rear wall of the chapel, before moving to the right to highlight one of the Osiris statues that stand on either side of the doorway to the 2nd chamber.[8] A further subtlety to this main alignment is created by a light-box, which shows a block of sunlight that slowly moves from the central axis of the temple to first illuminate the god Amun-Ra to then shining on the kneeling figure of Thutmose III before finally illuminating the Nile god Hapi.[8] Additionally, because of the heightened angle of the sun, around 41 days on either side of the solstice, sunlight is able to penetrate via a secondary light-box through to the innermost chamber.[8] This inner-most chapel was renewed and expanded in the Ptolemaic era and has cult references to Imhotep, the builder of the Pyramid of Djoser, and Amenhotep, son of Hapu, the overseer of the works of Amenhotep III.[9]

The solsticial alignment could be related to the fusion of the egyptian constellation of the ram with the sun, originating Amun-Ra, heavenly father of Hatshepsut, manifesting itself in theogamy.[10] Nine months later, at the autumn equinox, the Beautiful Feast of Opet would mark the pharaonic birth. As for the alignment of the 1st of February, it would be a marker of the date on which Amun-Ra pronounced the oracle that enthroned Hatshepsut as a female pharaoh.[10]

Historical influence

Hatshepsut’s temple is considered the closest Egypt came to classical architecture.[1] Representative of New Kingdom funerary architecture, it both aggrandizes the pharaoh and includes sanctuaries to honor the gods relevant to her afterlife.[11] This marks a turning point in the architecture of ancient Egypt, which forsook the megalithic geometry of the Old Kingdom for a temple which allowed for active worship, requiring the presence of participants to create the majesty. The linear axiality of Hatshepsut’s temple is mirrored in the later New Kingdom temples. The architecture of the original temple has been considerably altered as a result of misguided reconstruction in the early twentieth century AD.

Model of the temple complex

A walk-in model of the temple complex has been created since October 2016 in the freely available virtual world of Second Life. The main focus of this model is the overall architectural impression of the temples and gardens, but also some important murals of the Hatshepsut temple are shown (see links).

Gallery

South-western colonnade in the second court (looking west)

South-western colonnade in the second court (looking west) Northern colonnaded facade of the upper terrace

Northern colonnaded facade of the upper terrace Head of a statue of Hatshepsut

Head of a statue of Hatshepsut- Hatshepsut Temple

- Hatshepsut Temple

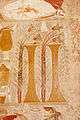

.jpg) Part of the Punt Relief

Part of the Punt Relief- Tempio di Hatshepsut

- Deir el-Bahari TIII

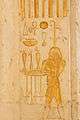

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Column detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Column detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Column detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Column detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, detail Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Column detail

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Column detail

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian sites, including sites of temples

External links

- Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Mission at the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari

- All Polish Deir el-Bahari Projects

- Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut (see index)

- Temple of Hatshepsut free high resolution images

References

- Katarzyna Kasprzycka, Reconstruction of sandstone sphinxes from the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, PAM 28 (2018)

- Zbigniew E. Szafrański, Remarks on royal statues in the form of the god Osiris from Deir el-Bahari, PAM 27/2 (2018)

- Franciszek Pawlicki, The Main Sanctuary of Amun-Re in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, Warsaw: PCMA, 2017

- Zbigniew E. Szafrański, Deir el-Bahari. Temple of Hatshepsut. In Ewa Laskowska-Kusztal (red.), Seventy Years of Polish Archaeology in Egypt, Warsaw: PCMA, 2007

- Janusz Karkowski, The Solar Complex in Hatshepsut’s Temple at Deir el-Bahari, Warsaw 2003.

- Zbigniew E. Szafrański (ed.), Queen Hatshepsut and her temple 3500 years later, Warsaw 2001.

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2006). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective Volume I (12th ed.). Victoria: Cengage Learning. p. 56. ISBN 0495573604.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Franciszek Pawlicki, Deir el-Bahari. The Temple of Queen Hatshepsut 1998/1999, PAM XI (2000)

- Strudwick, Nigel; Strudwick, Helen (1999). Thebes in Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor (1. publ. ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press. ISBN 0-8014-3693-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trachtenberg, Marvin; Hyman, Isabelle (2003). Architecture, from Prehistory to Postmodernity. Italy: Prentice-Hall Inc. ISBN 978-0-8109-0607-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkinson, Richard (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. United Kingdom: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05100-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Notes

- Trachtenberg & Hyman 2003, p. 71

- Kleiner 2006, p. 56

- Zbigniew E. Szafrański, Deir el-Bahari. Temple of Hatshepsut. In Ewa Laskowska-Kusztal (red.), Seventy Years of Polish Archaeology in Egypt, Warsaw: PCMA, 2007

- "Deir el-Bahari, Temple of Hatshepsut". pcma.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- "Deir el-Bahari: The opening of the Main Sanctuary of Amun-Re in the Temple of Hatshepsut". pcma.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- Archived March 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Patryk Chudzik (red.), 60 lat Stacji Badawczej w Kairze / 60 Years of the Research Centre in Cairo, Warszawa: PCMA 2019

- Furlong, David Winter Solstice Alignment at Deir El Bahari Archived 2013-11-17 at Archive.today – Photographic evidence of the winter solstitial alignment

- Wilkinson 2000, p. 178

- Fernández Pousada, Alfonso Daniel. "Significado de las alineaciones solares del Templo de Hatshepsut en Deir el-Bahari". Egiptología 2.0. XVII.

- Strudwick & Strudwick 1999, p. 80