Dixie

Dixie (also known as Dixieland) is a nickname for the Southern United States, especially those states that seceded to form the Confederate States of America.[5]

Region

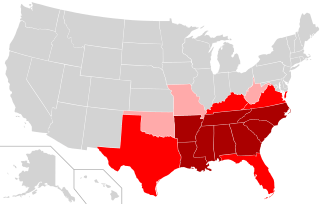

As a definite geographic location within the United States, "Dixie" is usually defined as the eleven Southern states that seceded in late 1860 and early 1861 to form the new Confederate States of America. They are (in order of secession): South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee. Maryland never seceded from the Union, but many of its citizens favored the Confederacy. While many of Maryland's representatives were arrested[6] to prevent secession,[7] both the states of Missouri and Kentucky produced Ordinances of Secession and were formally admitted into the Confederacy.[8] West Virginia was part of Virginia until 1863; counties that chose not to secede from the Union became part of West Virginia.

Although Maryland is not included in Dixie today, Maryland is on the Dixie side of the Mason–Dixon line; if the origin of the term Dixie is accepted as referring to the region south and west of that line, Maryland was in Dixie in 1760. It can also be argued that Maryland was, in 1860, part of Dixie, especially culturally.[9] In this sense, it would remain so into the 1970s, when an influx of people from the Northeast made the state and its culture significantly less Southern (especially Baltimore and the suburbs of Washington, DC).[10]

However, the location and boundaries of "Dixie" have, over time, become increasingly subjective and mercurial.[11] Today, it is most often associated with those parts of the Southern United States where traditions and legacies of the Confederate era and the antebellum South live most strongly.[12] The concept of "Dixie" as the location of a certain set of cultural assumptions, mind-sets and traditions (along with those of other regions in North America) was explored in the 1981 book The Nine Nations of North America.[13]

In terms of self-identification and appeal, the popularity of the word "Dixie" has been found to be declining. A 1976 study revealed that in an area of the South covering some 350,000 square miles (910,000 km2) (all Mississippi and Alabama, almost all of Georgia, Tennessee and South Carolina, and around a half of Louisiana, Arkansas, Kentucky, North Carolina and Florida) "Dixie" reached 25% of the popularity of "American" in names of commercial business entities.[14] A 1999 analysis found that between 1976 and 1999 in 19% of US cities sampled there was an increase of relative use of "Dixie", in 48% of cities sampled there was a decline and there was no change recorded in 32% of cities,[15] while a 2010 study found that in the course of 40 years the area in question shrank to just 40,000 square miles (100,000 km2), to the territory at the confluence of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida.[16] In 1976 at some 600,000 square miles (1,600,000 km2)[lower-alpha 1] "Dixie" reached at least 6% popularity of "American"; in 2010 the corresponding area was some 500,000 square miles (1,300,000 km2).[17]

Significant scholarship has been devoted to the mythology of Dixie and the South (including Lost Cause mythology) as developed "by the many attentions of northern artists to southern mythology, the North's fascination with aristocracy and lost causes, the national appeal of the agrarian myth, and the South's personification of that ideal, to say nothing of the North's persistent use of the South in the manipulation of her own racial mythology." [18][19]

In the 21st century, concerns over glorifying the Confederacy has led to the term being removed from some public references.[20][21][22][23]

Origin of the name

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the origin of this nickname remains obscure. The most common theories according to A Dictionary of Americanisms on Historical Principles (1951) by Mitford M. Mathews are:

- "Dixie" is derived from Jeremiah Dixon, a surveyor of the Mason–Dixon line, which defined the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania, separating free and slave states subsequent to the Missouri Compromise.[24] Evidence shows that 'Dixon' became 'Dixie' in a children's game played in New York back in the 1840s.[25]

- The word "Dixie" refers to currency issued first by the Citizens State Bank in the French Quarter of New Orleans and then by other banks in Louisiana.[26] These banks issued ten-dollar notes[27] labeled Dix on the reverse side, French for "ten". The notes were known as "Dixies" by Southerners, and the area around New Orleans and the French-speaking parts of Louisiana came to be known as "Dixieland".[5] Eventually, usage of the term broadened to refer to the Southern states in general.

- One apocryphal account claims that the word preserves the name of a Mr. Johan Dixie (sometimes spelled Dixy), a slave owner on Manhattan Island where slavery was legal until 1827. The story as told in Word Myths: Debunking Linguistic Urban Legends (2008) tells that Dixie's slaves were later sold in the South, and having formerly worked "Dixie's Land", told of the relatively less harsh treatment they faced while in the North. There is no evidence that this story is true.[28][29]

See also

- Bible Belt

- Deep South

- Dixie (song)

- Dixie (Utah)

- Dixieland Jazz

- Dixie Alley – a nickname sometimes given to the area due to it being particularly vulnerable to strong or violent tornadoes.

Notes

- from Eastern areas of Texas and Oklahoma to Southern areas of Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia and Virginia

References

- Oh, Soo. "Which states do you think belong in the South?". Vox. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Wilson, Charles & William Ferris Encyclopedia of Southern Culture ISBN 978-0-8078-1823-7; Univ. of Pennsylvania Telsur Project Telsur Map of Southern Dialect

- Vance, Rupert Bayless, Regionalism and the South, Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1982, p. 166 "West Virginia is found to have its closest attachment to the Southeast on the basis of agriculture and population."

- David Williamson (June 2, 1999). "UNC-CH surveys reveal where the 'real' South lies". Retrieved 22 Feb 2007.

- "Dixie". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- United States. War Department (1894). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 2. 1. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 684.

...all members of the Maryland Legislature assembled at Frederick City on the 17th instant known or suspected to be disloyal in their relations to the Government have been arrested.

- "The Southern Literary Messenger". Vol. 38 no. 1. Richmond: Wedderburn & Alfriend. 1864. p. 198.

The passage of any act of secession by the Legislature of Maryland must be prevented. If necessary all or any part of the members must be arrested. Exercise your own judgment as to the time and manner, but do the work effectively.

Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - "Ordinances of Secession". Historical Text Archive. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- "The General Assembly Moves to Frederick, 1861". Retrieved 25 Oct 2017.

- Rasmussen, Frederick (March 28, 2010). "Are we Northern? Southern? Yes". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- There is such a multitude of threads to the fabric called Dixie that official organizations draw boundaries enclosing anywhere from nine to seventeen states and call the place "the South."Joel Garreau (1981). The Nine Nations of North America. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 132. ISBN 0-395-29124-0.

- ""Where Does the South Begin?"". The Atlantic. 28 Jan 2011.

- Joel Garreau (1981). The Nine Nations of North America. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-29124-0.

- John Shelton Reed, "The Heart of Dixie: An Essay in Folk Geography", [in:] "Social Forces" 54/4 (1976), pp. 925-939

- Derek H. Alderman, Robert Maxwell Beavers, "Heart of Dixie Revisited: an Update on the Geography of Naming in the American South", [in:] "Southeastern Geographer" XXXlX/2 (1999), p. 196

- Christopher A. Cooper, H. Gibbs Knotts, "Declining Dixie: Regional Identification in the Modern American South", [in:] "Social Forces" 88/3 (2010), pp. 1083-1101

- Cooper, Gibbs Knotts 2010, p. 1090

- Gerster, Patrick; Cords, Nicholas (November 1977). "The Northern Origins of Southern Mythology". THE JOURNAL OF SOUTHERN HISTORY. XLIII (4): 567–582. doi:10.2307/2207006. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

- Cox, Karen L. (2011). Dreaming of Dixie: How the South was Created in American Popular Culture. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807834718.

- "Dolly Parton's Civil War-Themed 'Dixie Stampede' Attraction to Change Name". Rolling Stone. 11 Jan 2018.

- "Dixie Highway name condemned by Miami-Dade commissioners. 'Get over it? ... Hell no'". 5 Feb 2020.

- Shaffer, Claire (25 June 2020). "Dixie Chicks Change Name to 'The Chicks,' Drop Protest Song". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Amanda Petrusich (13 Jul 2020). "Why the Chicks Dropped Their "Dixie"". The New Yorker.

- John Mackenzie, "A brief history of the Mason-Dixon Line Archived 2018-07-17 at the Wayback Machine", APEC/CANR, University of Delaware; accessed 2017.01.05.

- A much more promising line of inquiry relates Dixie to the Mason-Dixon line, the demarcation between northern and southern states named after the surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon in the 1770s. Jonathan Lighter, the editor of the Historical Dictionary of American Slang, pieced together evidence that connects the Mason-Dixon line to Dixie via an unexpected intermediary: a children’s game played in New York City. Zimmer, Ben (2020-06-26). "What 'Dixie' Really Means". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- "Dixie" Originated From Name "Dix" An Old Currency - New Orleans American May 29 1916, Vol. 2 No. 150, Page 3 Col. 1 Archived 2011-08-07 at the Wayback Machine Louisiana Works Progress Administration (WPA), Louisiana Digital Library

- Ten Dollar Note Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine George Francois Mugnier Collection, Louisiana Digital Library

- Wilton, David (2008). Word Myths: Debunking Linguistic Urban Legends. Oxford University Press. p. 147.

- Richard Campanella, Lincoln in New Orleans, accessed 2020.06.27.

Further reading

- Reed, John Shelton (with J. Kohl and C. Hanchette) (1990). The Shrinking South and the Dissolution of Dixie. Social Forces. pp. 69, 221–233.

- Sacks, Howard L. and Judith Rose. Way Up North In Dixie. (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993)