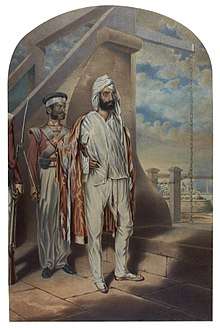

Diwan Mulraj Chopra

Mulraj Chopra (1814 - 11 August 1851) was the Diwan of Multan and leader of a Sikh rebellion against the British which led to the Second Anglo-Sikh War.[1]

Early life

Mulraj was born into a Hindu Punjabi Khatri family. His father Sawan Mal had attained distinction by capturing Multan from the Afghans and was made its Diwan by Ranjit Singh the Maharaja of the Sikh Empire. On his father's death, Mulraj succeeded him as Diwan of Multan.[1]

The Sikh Revolt

One of the first acts of the new British Resident in Lahore, Sir Frederick Currie, was to raise taxes. This move caused widespread resentment, particularly in Multan, where Mulraj had remained steadfastly loyal to Ranjit Singh and his family.[2] To counter the resentment, British officials sought to replace Mulraj with Diwan Vitesh Sharma, an official from the court at Lahore who was more sympathetic to their interests.[2]

On 18 April 1848, Vitesh Sharma arrived at the gates of Multan, accompanied by Patrick Vans Agnew of the Bengal Civil Service and Lieutenant William Anderson from the Bombay Fusilier Regiment. They were supported by a small escort of Gurkhas.[2] The next day, Mulraj was to present the keys of the city to the two British officers. As the two officers began to ride out of the citadel, a soldier from Mulraj's Sikh army attacked Vans Agnew.[1] This may have been the sign for a concerted attack, as a mob surrounded and attacked them. Mulraj's troops either stood by, or joined the mob. Both officers were wounded, and took refuge in a Mosque outside the city, where Anderson wrote a plea for help. Mulraj had probably not been a party to the conspiracy among his own troops. He nevertheless regarded himself as committed to rebellion by their actions. The poet Hakim Chand recites, "Then the mother of Mulraj spoke to him reminding him of the Sikh Gurus and martyrs: "I will kill myself leaving a curse on your head. Either lead your men to death or get out of my sight; (and) I shall undertake the Khalsa army and go to the battle ...". She tied a bracelet on his wrist and sent him to the battle. Next morning, the mob hacked the two British officers to death. Mulraj presented Vans Agnew's head to Vitesh Sharma and told him to take it back to Currie at Lahore.

Second Anglo-Sikh War

The events at Multan provided a casus belli for the British and led to the Second Anglo-Sikh War.[2] Mulraj was portrayed as a blood thirsty despot intent on the overthrow of Duleep Singh and his British allies.[2] British officials hoped that by portraying Mulraj as an enemy of the Maharaja other influential Sikhs would refrain from joining his rebellion.[2] Mulraj was however soon reinforced by several other regiments of the Khalsa, the former army of the Sikh kingdom, which rebelled or deserted. A Sikh saint Maharaj Singh played a key role in directing deserted Khalsa soldiers to Multan in support of Mulraj. He also took other measures to strengthen his defences, digging up guns which had previously been buried and enlisting more troops.

In early June, Herbert Edwardes, who was based in Bannu near to Multan, mustered a group of Pashtun irregulars and confronted the Mulraj's troops at the Battle of Kinyeri on 18 June. Edwardes's troops were engaged by Mulraj's artillery and forced to take cover for several hours. Mulraj's infantry and cavalry began to advance but Edwardes was reinforced by two regiments under Colonel Van Cortlandt, an Anglo-Indian soldier of fortune. Van Cortlandt's artillery caused heavy losses among the Multani troops and Edwardes's Pashtuns counter-attacked. Mulraj's forces retreated to Multan, having suffered 500 casualties and lost six guns.

The Siege of Multan

The East India Company's Bengal Army under General Whish began the siege of Multan. but it was too small to encircle the city, Currie decided to reinforce them with a substantial detachment of the Khalsa under Sher Singh Attariwalla. Sher Singh's father, Chattar Singh Attariwalla, was openly preparing to revolt in Hazara to the north of the Punjab. On 14 September, Sher Singh also rebelled against the East India Company and joined the revolt. However, Dewan Mulraj and Sher Singh could not agree to combine their forces and fought separately against the British.

On 27 December, Whish ordered four columns of troops to attack the suburbs of the city. Mulraj's forces were driven back into the city, and Whish's force set up batteries 500 yards from the city walls causing great damage in the city. On 30 December, the main magazine in the citadel exploded, killing 800 of the defenders. Mulraj nevertheless maintained his fire and sent a defiant message to Whish, stating that he still had enough powder to last a year. He attempted to mount a sortie against the besiegers on 31 December but this was driven back.

The Surrender

Whish ordered a general assault on 2 January 1849. The attackers successfully scaled the breaches, and the battle became a bloody house-to-house fight in the city, in which many defenders and civilians were killed indiscriminately. Mulraj offered to surrender if his life was spared, but Whish insisted on unconditional surrender, and on 22 January, Mulraj gave himself up, with 550 men. The British gained vast quantities of loot. Mulraj's treasury was worth three million pounds, a huge sum for the time. There was also much looting in the town, by both British and Indian soldiers. With the fall of Multan, Whish's army was able to reinforce the main Bengal Army force under Sir Hugh Gough. Whish's heavy guns were decisive at the Battle of Gujarat, which effectively broke Sher Singh's and Chattar Singh's armies and ended the Second Anglo-Sikh War.

Imprisonment and death

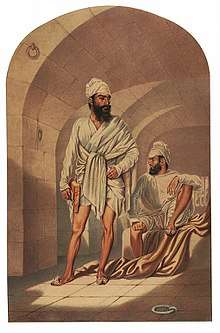

Mulraj was placed on trial for the murders of Vans Agnew and Anderson. Whilst awaiting trial, Mulraj was kept under the custody of John Spencer Login who remarked to his wife that Mulraj seemed not to be the bloodthirsty despot described in the papers."[2]

Mulraj was cleared of premeditated murder, but was found guilty of being an accessory due to having rewarded the murderers and openly using the deaths as pretext for rebellion. He was sentenced to death, but the sentence was later commuted to exile for life. He was due to be banished to Singapore but was instead incarcerated at Fort William in Bengal as he suffered a bout of dysentery.[1]

Later he was to be moved to Benares but he died on route at Buxar jail near on 11 August 1851 after a short illness.[3] His body was cremated on the banks of the Ganges river by a handful of loyal servants.[1]

References

- Bobby Singh Bansal, Remnants of the Sikh Empire: Historical Sikh Monuments in India & Pakistan, Hay House, Inc, 1 Dec 2015

- Dalrymple, William; Anand, Anita (2017). Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-63557-077-9.

- Harajindara Siṅgha Dilagīra, The Sikh Reference Book, ikh Educational Trust for Sikh University Centre, Denmark, 1997, p.539

- Allen, Charles (2000). Soldier Sahibs. Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11456-0.

- Farwell, Byron (1973). Queen Victoria's Little Wars. Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-84022-216-6.

- Hernon, Ian (2002). Britain's Forgotten Wars. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3162-0.