Dionysus Cup

The Dionysus Cup is the modern name for one of the best known works of ancient Greek vase painting, a kylix (drinking cup) dating to 540–530 BC. It is one of the masterpieces of the Attic Black-figure potter Exekias and one of the most significant works in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Munich.[1]

Description

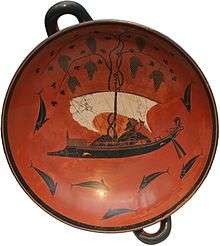

The cup is 13.6 cm high and has a diameter of 30.5 cm. It is complete and composed of only a few large sherds. The inside image, the tondo, takes up almost the entire interior of the cup. In the centre, a sailing ship is depicted, travelling from right to left. The prow of the ship is decorated like an animal's head, while the rudder is clearly discernable at the rear. Within the ship is a well over life sized figure, the god Dionysus. The sail, unlike the rest of the image, is painted white, a common stylistic element in the black figure style. Vines grow from the mast, with three large clusters of grapes on the right and four on the left. Dolphins swim below the ship—two towards the right, three towards the left—and a further dolphin is found on the right and the left hand sides of it. Although this is not realistic perspective, it could indicate that the dolphins are swimming around the ship. Like the vine, dolphins are symbols of Dionysos. In addition to this broad outline of the image, there are many detailed features. Two small dolphins are incised on the side of the ship. The long-haired, bearded god wears an ivy crown and holds a cornucopia in his hand. His tunic bears a fine pattern. On the outside, around each of the handles, six warriors stand over a corpse. The space between the handles is decorated with a stylised face with large eyes and a small nose.[2]

Context

Two meanings have been suggested for the interior image. Most common is the suggestion that is a reference to the seventh Homeric Hymn, in which it is explained how Dionysus was kidnapped by Etruscan pirates, who were unaware of his identity. The god confuses their thoughts and causes them to jump into the water, where they transform into dolphins. A second possibility is that the arrival of Dionysus at the Athenian Anthesteria is depicted. The images around the handles probably depict the battles for the corpses of Patroclus and Achilles, with the naked corpse being Patroclus.[3]

Innovation

The cup shows numerous technical innovations. As a potter, Exekias took older forms and reshaped them into a completely new one. This form, the so-called Cup type A with a thicker foot, a ring around the stem, and a deep, broad bowl, would quickly become the dominant form. The "eye-cup" motif was originally introduced by Exekias, possibly with this piece. Later on the nose in between the eyes grew rarer. The decoration around the handles was similarly new, but unlike the other innovations it did not catch on. Neither did the tondo nearly completely filling the inside of the cup, which was notably imitated later on by the Penthesilea Painter, but is otherwise rather uncommon. Hitherto it had been common in general for the interior of a cup to be decorated with a small tondo depicting a gorgoneion. Also new, but only employed experimentally for a few years and then only rarely was the technique of Intentional Red, in which the background was made an intense, dark red clay. For this too, the cup is the earliest example. Inside of the cup, the decoration has no horizon line or specific orientation other than the ship and the grapes. [4]

History

It is clear that Exekias was the potter, since he signed the foot with an inscription reading EΞΣΕΚΙΑΣ ΕΠΟΕΣΕ - "Exsekias made this". The attribution of the painting to him derives from stylistic comparisons. Although the internal chronology of Exekias' works is still not fully understood, the cup is generally placed among his later works. The exact date varies between 540 and 530 BC.

The cup was found during Lucien Bonaparte's excavations at Vulci and acquired for Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1841.

References

- Inventory number 8729 (formerly 2044); evaluation of worth by John Boardman, Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen. Mainz 1977, p. 64 and Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei. Stuttgart 2002, p. 121

- Description follows Matthias Steinhart, "Exekias" in Künstlerlexikon der Antike. Vol. 1. München, Leipzig 2001, pp. 249–252.

- Context after Matthias Steinhart, "Exekias" in Künstlerlexikon der Antike. Vol. 1. München, Leipzig 2001, pp. 249–252.

- Artstor. "Artstor". library.artstor.org. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

Bibliography

- John Beazley. Attic Black-figure Vase-painters. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1956, p. 146 No. 21.

- John Boardman. Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen. Ein Handbuch. Zabern, Mainz 1977, ISBN 3-8053-0233-9, p. 64.

- Matthias Steinhart. "Exekias" in Künstlerlexikon der Antike. Vol. 1. Saur, München, Leipzig 2001, pp. 249–252.

- Thomas Mannack. Griechische Vasenmalerei. Eine Einführung. Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-8062-1743-2, p. 121.

- Berthold Fellmann. München, Antikensammlungen, ehemals Museum antiker Kleinkunst. Vol. 13: Attische schwarzfigurige Augenschalen (= Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Deutschland. Vol. 77). C. H. Beck, München 2004, ISBN 3-406-51960-1, pp. 14–19 tbl. 1-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dionysos Cup (Exekias). |

- Attic Black-figue Eye cup of Exekias (München, Staatliche Antikensammlung) in the archaeological database Arachne