Dermoid cyst

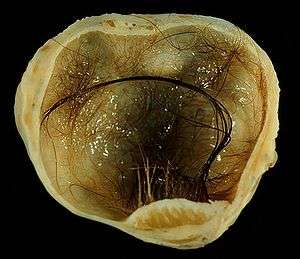

A dermoid cyst is a teratoma of a cystic nature that contains an array of developmentally mature, solid tissues. It frequently consists of skin, hair follicles, and sweat glands, while other commonly found components include clumps of long hair, pockets of sebum, blood, fat, bone, nail, teeth, eyes, cartilage, and thyroid tissue.

| Dermoid cyst | |

|---|---|

| |

| A small (4 cm) dermoid cyst of an ovary, discovered during a C-section | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

As dermoid cysts grow slowly and contain mature tissue, this type of cystic teratoma is nearly always benign. In those rare cases wherein the dermoid cyst is malignant, a squamous cell carcinoma usually develops in adults, while infants and children usually present with an endodermal sinus tumor.[1]:781

Location

Due to its classification, a dermoid cyst can occur wherever a teratoma can occur.

Vaginal and ovarian dermoid cysts

Ovaries normally grow cyst-like structures called follicles each month. Once an egg is released from its follicle during ovulation, follicles typically deflate. Sometimes fluid accumulates inside the follicle, forming a simple (containing only fluid) cyst.[2] The majority of these functional cysts resolve spontaneously.

While all ovarian cysts can range in size from very small to quite large, dermoid cysts are not classified as functional cysts. Dermoid cysts originate from totipotential germ cells (which are present at birth) that differentiate abnormally, developing characteristics of mature dermal cells. Complications exist, such as torsion (twisting), rupture, and infection, although their incidence is rare. Dermoid ovarian cysts which are larger present complications which might require removal by either laparoscopy or laparotomy (traditional surgery).[3][4] Rarely, a dermoid cyst can develop in the vagina.[5][6][7]

- Large ovarian cyst

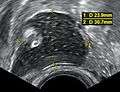

Dermoid cyst in vaginal ultrasonography

Dermoid cyst in vaginal ultrasonography A complex cyst due to a dermoid as seen on ultrasound

A complex cyst due to a dermoid as seen on ultrasoundMark.png) A complex cyst due to a dermoid as seen on CT. Arrow points to bone or teeth.

A complex cyst due to a dermoid as seen on CT. Arrow points to bone or teeth.

Periorbital dermoid cysts

Dermoid cysts can appear in young children, often near the lateral aspect of the eyebrow (right part of the right eyebrow or left part of the left eyebrow). Depending on the perceived amount of risk, these are sometimes excised or simply kept under observation.

An inflammatory reaction can occur if a dermoid cyst is disrupted, and the cyst can recur if it is not completely excised. Sometimes complete excision is not practical if the cyst is in a dumbbell configuration, whereby it extends through a suture line in the skull.

If dermoid cysts appear on the medial aspect, the possibility of an encephalocele becomes greater and should be considered among the differential diagnoses.

Other areas where a dermoid cyst may appear are the brain, scrotum and the pharynx.

Dermoid cysts develop during pregnancy. They occur when skin cells and things like hair, sweat glands, oil glands or fatty tissue get trapped in the skin as a baby grows in the womb. Dermoid cysts are present at birth (congenital) and are common. It can be months or years before a dermoid cyst is noticed on a child because the cysts grow slowly.

Dermoid cyst symptoms are minor and the cysts are usually painless. They are not harmful to a child’s health. If they become infected, the infection must be treated and the cyst should be removed. It is easier to remove cysts and prevent scars if the cyst is removed before it gets infected.

Spinal dermoid cysts

Spinal dermoid cysts are benign ectopic growths thought to be a consequence of embryology errors during neural tube closure. Their reported incidence is extremely rare, accounting for less than 1% of intramedullary spinal cord tumours. It has been proposed that a possible 180 cases of spinal dermoid tumours have been identified over the past century in the literature.[8][9]

Dermoid cysts more often involve the lumbosacral region than the thoracic vertebrae and are extramedullary presenting in the first decade of life.

Various hypotheses have been advanced to explain the pathogenesis of spinal dermoids, the origin of which may be acquired or congenital.

- Acquired or iatrogenic dermoids may arise from the implantation of epidermal tissue into the subdural space i.e. spinal cutaneous inclusion, during needle puncture (e.g. lumbar puncture) or during surgical procedures on closure of a dysraphic malformation.[9][10]

- Congenital dermoids, however, are thought to arise from cells whose position is correct but which fail to differentiate into the correct cell-type. The long-time held belief was that the inclusion of cutaneous ectodermal cells occurred early in embryonic life, and the displaced pluripotent cells developed into a dermoid lesion.[10][11]

Spinal abnormalities, e.g. intramedullary dermoid cysts may arise more frequently in the lumbosacral region (quite often at the level of the conus medullaris) and may be seen with other congenital anomalies of the spine including posterior spina bifida occulta as identified by the neuroradiological analysis.[8][11]

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

A small dermoid cyst on the coccyx can be difficult to distinguish from a pilonidal cyst. This is partly because both can be full of hair. A pilonidal cyst is a pilonidal sinus that is obstructed. Any teratoma near the body surface may develop a sinus or a fistula, or even a cluster of these. Such is the case of Canadian Football League linebacker Tyrone Jones, whose teratoma was discovered when he blew a tooth out of his nose.[12]

Treatment

Treatment for dermoid cyst is complete surgical removal, preferably in one piece and without any spillage of cyst contents. Marsupialization, a surgical technique often used to treat pilonidal cyst, is inappropriate for dermoid cyst due to the risk of malignancy.

The association of dermoid cysts with pregnancy has been increasingly reported. They usually present the dilemma of weighing the risks of surgery and anesthesia versus the risks of untreated adnexal mass. Most references state that it is more feasible to treat bilateral dermoid cysts of the ovaries discovered during pregnancy if they grow beyond 6 cm in diameter.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dermoid cysts. |

- Dermoid sinus, more commonly known as a pilonidal cyst

- Proliferating trichilemmal cyst

- List of cutaneous conditions

References

- Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- "Ovarian Cysts". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

- Hoo WL, Yazbek J, Holland T, Mavrelos D, Tong EN, Jurkovic D (August 2010). "Expectant management of ultrasonically diagnosed ovarian dermoid cysts: is it possible to predict outcome?". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 36 (2): 235–40. doi:10.1002/uog.7610. PMID 20201114.

- "Medical Definition of Dermoid cyst of the ovary". MedicineNet.

- Humphrey, Peter A.; Dehner, Louis P.; Pfeifer, John D. (22 February 2018). The Washington Manual of Surgical Pathology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781765275. Retrieved 22 February 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Tumours of the Vagina; Chapter Six" (PDF). International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. pp. 291–311. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-08.

- "Vulva and Vagina tumors: an overview". atlasgeneticsoncology.org. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- Najjar MW, Kusske JA, Hasso AN (October 2005). "Dorsal intramedullary dermoids". Neurosurgical Review. 28 (4): 320–5. doi:10.1007/s10143-005-0382-9. PMID 15739068.

- van Aalst J, Hoekstra F, Beuls EA, Cornips EM, Weber JW, Sival DA, Creytens DH, Vles JS (2009). "Intraspinal dermoid and epidermoid tumors: report of 18 cases and reappraisal of the literature". Pediatric Neurosurgery. 45 (4): 281–90. doi:10.1159/000235602. PMID 19690444.

- Roth M, Hanák L, Schröder R (June 1966). "Intramedullary dermoid". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 29 (3): 262–4. doi:10.1136/jnnp.29.3.262. PMC 496030. PMID 5937643.

- Muraszko K, Youkilis A (May 2000). "Intramedullary spinal tumors of disordered embryogenesis" (PDF). Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 47 (3): 271–81. doi:10.1023/A:1006474611665. hdl:2027.42/45389. PMID 11016743.

- Maki, Allan (November 16, 2006). "Maki:Jones returns to say goodbye". The Globe and Mail.