Derech Mitzvosecha

Derech Mitzvosecha, also titled Sefer Hamitzvos (Hebrew: דרך מצותך: ספר המצות), is an interpretive work on the Jewish commandments authored by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn (1789–1866), the third Rebbe of the Chabad Hasidic movement. The work is considered a fundamental text of Chabad philosophy.[1][2]

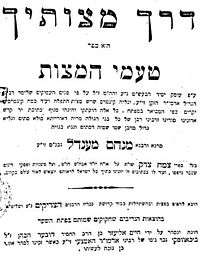

Derech Mitzvosecha, 1912 edition | |

| Author | Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn ("Tzemach Tzedek"), the third Rebbe of Chabad |

|---|---|

| Language | Hebrew |

| Subject | Jewish mysticism, Chabad philosophy |

| Genre | non-fiction |

| Published | 7x10 Hardcover, 570pp, (Kehot Publication Society, Brooklyn New York) |

| ISBN | 0826655904 |

.jpg) |

| Part of a series on |

| Chabad |

|---|

| Rebbes |

|

| Places and landmarks |

| Customs and holidays |

| Organizations |

|

| Schools |

| Chabad philosophy |

| Texts |

| Outreach |

| Terminology |

| Chabad offshoots |

Interpretation of the commandments

In Derech Mitzvosecha, Rabbi Menachem Mendel interprets the Jewish commandments ("mitzvos") according to Kabbalistic and Hasidic teachings. Topics include the commandments of belief in God, prayer, love of a fellow Jew, Tzitzit (fringes on four cornered garments) and Tefillin (phylacteries), and many others.[2] The work provides a Hasidic perspective on fundamental Jewish rites and observances.[3]

In some cases, Rabbi Menachem Mendel seeks to clarify or reconcile earlier rabbinic interpretations of the commandments, especially where earlier rabbinic authorities disagree on the matter. In this regard, Hasidic interpretations are employed to refine the statements of earlier authorities and/or to clarify or resolve their differences.[4]

Love of another Jew

In Derech Mitzvosecha Rabbi Menachem Mendel discusses the commandment to love one's fellow and not to hate him/her[5] and questions the story in the Talmud concerning Hillel the Elder and the convert. Hillel instructed a non-Jew wishing to convert "what to you is hateful do not do to your friend, this is the (root of) the entire Torah, the rest is commentary. Go and learn."[6]

For Rabbi Menachem Mendel, the idea of loving one's fellow should only be considered the root of all commandments that relate to human interactions, "between man and his friend" (bein adam l'chaveiro), but not to those that are "between man and God" (bein adam l'makom).

Rabbi Menachem Mendel resolves this question by introducing the Kabbalistic idea that the souls of the Jewish people compose a "single body"; each individual represents a particular limb.[7] Based on this concept, every Jew is obligated to love his or her fellow though the other may have some deficiency, just as the individual often overlooks his or her own faults due to the natural love one has for one's self. When this kind of "self love" is extended to each other person, it achieves a very strong unity of spirit.

According to Rabbi Menachem Mendel, this unity is representative of the unity between God and the Jewish people and is the root of all the commandments, for aside from the specifics of the individual commandment, each serve the additional function of uniting the Jews with God. Thus each commandment may be said to be the "commentary" of the commandment to love one's fellow.[8]

Publication

Rabbi Menachem Mendel published few of his works during his lifetime. The first edition of Derech Mitzvosecha was in Poltava (current day Ukraine), 1912-1913.[9] Later editions were published by Kehot Publication Society in Brooklyn, New York.

English edition

An English edition of Derech Mitzvosecha was translated by Rabbi Eliyahu Touger and published in 2004 by the Chabad publishing house Sichos in English. The English edition translates selected chapters from Rabbi Schneersohn's work.[10]

Appendices

The Kehot editions include a number of appendices in the work, including Kitzur Tanya, a summary of the Tanya, the classic Chabad work by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi.

References

- Miller, Chaim.The Gutnick Edition Chumash - Book of Genesis. Kol Menachem. 2005. Accessed May 8, 2014.

- Derech Mitzvosecha. Kehot Publication Society. Accessed May 8, 2014.

- Tzemach Tzedek. Shturem.org. Accessed May 8, 2014.

- Brackman, Eli. "Discovering G-d in the Opening of the Oxford Huntington Manuscript of Maimonides." Chabad of Oxford. oxfordchabad.org. March 28, 2013. Accessed May 8, 2014.

- See Leviticus, 19:17-18.

- Shabbat (Talmud Bavli) 31b.

- Vital, Chaim. Sefer Hagilgulim, Chapt. 1, Par. 2.

- Schneersohn, Menachem Mendel. "Issur Sinas Yisroel, Umitzvas Ahavas Yisroel." Derech Mitzvosecha. Kehot Publication Society. (2006): pp. 55-58.

- Tzemach Tzedek. ChabadLibrary.org. Accessed May 8, 2014.

- Schneersohn, Menachem M. Selections from Derech Mitzvosecha: A Mystical Perspective on the Commandments. Trans. Eliyahu Touger. Sichos in English. Brooklyn: New York. 2004. Accessed May 8, 2014.

External links

- Derech Mitzvosecha Hebrew edition on HebrewBooks.org

- Derech Mitzvosecha English edition on HebrewBooks.org