Defensive Organization of Corsica

The Defensive Organization of Corsica (Organisation Défensive de la Corse) was the French military organization that in 1940 was responsible for the defense of the French island of Corsica against a potential invasion by Fascist Italy. As part of the overall effort to fortify France's borders which included the Maginot Line, the fixed Corsican defenses were constructed in parallel with the Maginot Line, using the same organizational structure and similar designs, albeit scaled back in size, cost and fighting power. The Corsican defenses were designed to deter an Italian landing on the south end of Corsica, and to support artillery batteries capable of controlling the Strait of Bonifacio between Corsica and the Italian island of Sardinia, separated by only twelve kilometers. As World War II unfolded, no attempt was made by Italian forces to mount an opposed landing on Corsica. The island was instead occupied in November 1942. In 1943 Corsica saw fighting when German forces moved from Sardinia. Most of the fortified positions remain to the present day.

Concept and organization

During the inter-war period, Corsica's defenses were first examined in 1926, when General Debeney requested a study of the island's defenses from Vice-Admiral Salaun, the French Navy chief of staff. The island was only twelve kilometres (7.5 miles) from the Italian island of Sardinia across the Strait of Bonifacio, and was regarded as weakly defended. Salaun's report indicated that the island's capital, Ajaccio, was relatively well defended by old 120 mm (4.7 in) field guns, but that the areas on Bonifacio in the south and Bastia in the north were vulnerable to amphibious assault. Both attack and defense would be hampered by the island's poorly developed road network. Bonifacio, the closest point to Sardinia, could control the straits and provide a means of counterattacking Italian territory. In 1928 Bonifacio received five batteries of mounting a total of eight 190 mm guns and six 95 mm guns, both types of late 19th-century manufacture. At the same time, two 340 mm gun turrets were proposed for Bonifacio, similar to those eventually installed at Battery Cepet in Toulon and at Bizerte in Tunisia. The 200 million-franc cost of these batteries caused the turret project to be placed in a low-priority status.[1]

General Fournier, in charge of Corsican defenses in 1932, was directed by the Ministry of War on 13 April 1928 to prepare a defensive plan for the island. Fournier prepared an ambitious plan, proposing roads, airfields, telephone communications and other measures, which were projected to cost as much as 6 billion francs. Fournier was told to make do with 42 million francs. Exercises in 1929 showed up the vulnerability of Bonifacio, prompting Fournier to propose a 10 million-franc program to defend the southern beaches and the roads near Bonifacio. However, while the French Senate was amenable to funding, none was provided, and the 42 million-franc program was cut from the 1930 budget.[1]

Bonifacio's defenses were augmented in October 1932 with eight 194 mm guns in the town's citadel, four 138 mm guns and four 75 mm anti-aircraft guns at Bocca-di-Valle, four 145/155 guns at Sotta and six 164 mm guns at Monte-Léone. Many of these weapons had sufficient range to fire across the straits, particularly the guns at Sotta, which had a range of 20 kilometres (12 mi). These open emplacements lacked close-range defenses and were vulnerable to a landing behind the main artillery line. However, from 1931 the Commission d'Organisation des Régions Fortifiés, or CORF, was directed to advise on the defense of Corsica. The same year, a proposal was approved by the Army and Navy to fortify Corsica. The programme included improvements to infrastructure, with new roads and telephone communications, as well as the construction of casemates and ouvrages around Bonifacio. Costs were estimated in 1933 at 27 million francs, about half of which was to be spent on fortifications, with the remainder devoted to roads and communications.[1]

Construction

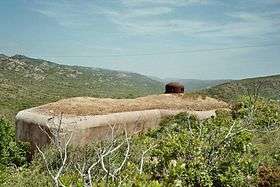

Construction of the CORF positions began in 1932, concentrating on the southern end of Corsica with three objectives: fortification of beaches suitable for the landing of an invasion force, control of the road between Porto-Vecchio and Bonifacio, and defense of the Pertusato plateau behind Bonifacio, site of several of the artillery batteries. A total of twelve infantry casemates and three artillery casemates were completed in 1932–1933.[2]

CORF was disestablished at the end of 1935. As war with Italy and Germany threatened in 1939, new measures were proposed for Corsican defenses. 5.4 million francs were allocated to improve the defenses of Bastia, building two casemates and two blockhouses. In the south, fifteen infantry shelters or abris were built in the Corpo-de-Verga area, known as the "Mollard Line," named after the island's military commander.[3] These positions were built by the Military Works Arm (Main d'Oeuvre Militaire, or MOM), which was responsible for many hastily built fortifications of the immediate pre-war period.[4]

Command

Corsica was under the overall command of the General Mollard. Mollard's troops included the 363rd Infantry Demi-Brigade (363e Demi-Brigade d'Infanterie) (363 DBI) with four (later three) battalions, the 373rd Alpine Infantry Demi-Brigade (373 Demi-Brigade Alpine d'Infanterie) (373e DBIA) with seven battalions, and the 43rd Squadron of the 10th Dragoons Regiment (cavalry) (43e Escadron du 10e Régiment de Dragons). Another three or four battalions from various units rounded out the force, supported by the 92nd Artillery Group.[5]

Description

All works were built by CORF unless otherwise noted.

Northern Corsican Group

Colonel d'Omano, commander

Subsector of Calvi

VIII/373rd DBIA

Sub-sector of Bastia

X/373rd DBIA, 174/405th battery DCA

- Blockhaus de l'Arinella: Blockhouse with two FM

- Casemate de 'Arinella: Double casemate with two JM/AC47, two JM and one GFM-B (never installed)

- Blockhaus de Saint-Florent: Blockhouse with two FM

- Casemate de Saint-Florent: Double casemate with two JM/AC47, two JM and one GFM-B (never installed)[6]

Sub-sector of Golo-Cervione

IX/373rd DBIA

Southern Corsica Group

Lieutenant Colonel Ricatte, followed by Colonel Denis from May 1940.

Sub-sector of Porto-Vecchio

A light infantry company

- Casemate de l'Aréna: Artillery casemate with one 75mm gun firing to the north

- Casemate de Ziglione: Single casemate with one JM

- Casemate de Georges-Ville: Double casemate with two JM, one GFM

- Casemate de Saint-Cyprien: Artillery casemate with one 75mm gun firing to the south

- Casemate de Santa-Giulia: Single casemate with one JM and one GFM[6]

Sub-sector of Bonifacio

V/373rd DBIA, I and III/363rd DBIA, 150th regional battalion, 3rd and 8th batteries 92nd Artillery Regiment, 175/405th battery DCA

- Casemate de Spinella Ouest: Single casemate with one JM and one mortar cloche

- Casemate de Spinella Est: Single casemate with one JM, one mortar cloche and one GFM

- Casemate de Ventilegne: Single casemate with one JM

- Casemate de Catarello: Single casemate with one JM, one mortar and one GFM

- Casemate de Pertusato I: Single casemate with one JM and one GFM

- Abri de Pertusato II: Underground infantry shelter for 58 men (MOM)

- Abri de Pertusato III: Underground infantry shelter for 34 men (MOM)

- Abrie de Pertusato IV: Underground infantry shelter for 18 men with an FM embrasure (MOM)

- Casemate de Pertusato V: Casemate with one mortar

- Abri de Pertusato VI: Underground infantry shelter for 34 men (MOM)

- Abri de Pertusato VII: Underground infantry shelter for 70 men with an FM embrasure (MOM)

- Batterie de Pertusato

- Casemate de Santa-Manza: Artillery casemate with two 75mm guns firing to the north

- Casemate de Capo-Bianco Nord: Single casemate with ine JM, one GFM

- Casemate de Capo-Bianco Sud: Single casemate with ine JM, one GFM

- Casemate de Rondinara: Single casemate with two JM, one GFM[6]

Sub-sector of Sartène

II/363rd DBIA

Independent sub-sectors

Sub-sector of Aleria

VII/363rd DBIA, VIII/373rd DBIA, 171/405th battery DCA

Sub-sector of Ajaccio

VI/373rd DBIA, 172nd and 173rd batteries 405th DCA

History

Corsica was not directly attacked by ground forces in 1940. Between 15 June and 20 June the Italian Air Force bombed Propriano, Porto-Vecchio, Bonifacio and Calvi, with little effect.[7] Corsica was occupied by Italian forces after the armistice of June 25, 1940, but remained French territory under the Vichy French government. During the fighting of 1943, in which German forces moved from Sardinia to Corsica and then to Sicily, the Georges-Ville casemate was destroyed and the casemates at Ventilègne and Catarello were damaged. The artillery casemates' 75mm guns were salvaged after the war and sent to re-arm positions in the Fortified Sector of the Maritime Alps.[8]

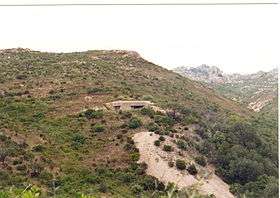

Present status

The casemates at Rondinara,[9] Santa Manza[10] and other locations are reported to be in good condition and accessible.

References

- Mary, Tome 5, pp. 81–82

- Mary, Tome 5, pp. 82–83

- Mary, Tome 5, p. 83

- Mary, Tome 5, p. 85

- Mary, Tome 5, pp. 88–89

- Mary, Tome 5, pp. 81–89

- Mary, Tome 5, p. 89

- Mary, Tome 5, p. 156

- "Rondinara Maginot Bunker, Suartone". ExploGuide. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "Santa Manza Maginot Bunker, Suartone". ExploGuide. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

Bibliography

- Allcorn, William. The Maginot Line 1928–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84176-646-1

- Kaufmann, J.E. and Kaufmann, H.W. Fortress France: The Maginot Line and French Defenses in World War II, Stackpole Books, 2006. ISBN 0-275-98345-5

- Kaufmann, J.E., Kaufmann, H.W., Jancovič-Potočnik, A. and Lang, P. The Maginot Line: History and Guide, Pen and Sword, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84884-068-3

- Mary, Jean-Yves; Hohnadel, Alain; Sicard, Jacques. Hommes et Ouvrages de la Ligne Maginot, Tome 1. Paris, Histoire & Collections, 2001. ISBN 2-908182-88-2 (in French)

- Mary, Jean-Yves; Hohnadel, Alain; Sicard, Jacques. Hommes et Ouvrages de la Ligne Maginot, Tome 4 - La fortification alpine. Paris, Histoire & Collections, 2009. ISBN 978-2-915239-46-1 (in French)

- Mary, Jean-Yves; Hohnadel, Alain; Sicard, Jacques. Hommes et Ouvrages de la Ligne Maginot, Tome 5. Paris, Histoire & Collections, 2009. ISBN 978-2-35250-127-5 (in French)

External links

- Le Secteur défensif de Corse at wikimaginot.eu }}.

- Corse (organisation défensive fortifiée de la) at fortiff.be/}}.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Defensive Organization of Corsica. |