Deephams Sewage Treatment Works

Deephams Sewage Treatment Works is a sewage treatment facility close to Picketts Lock, Edmonton, England. The outflow discharges via Pymmes Brook into the River Lee Navigation at Tottenham Lock.[1] The treatment works was upgraded in 2012/13.[2][3]

| Deephams Sewage Treatment Works | |

|---|---|

The entrance to Deephams Sewage Treatment Works at Picketts Lock Lane | |

Deephams Sewage Treatment Works shown within Greater London | |

| Type | Waste Water Treatment Works |

| Location | Edmonton, Greater London, England |

| Coordinates | 51°37′34″N 0°02′02″W |

| Area | 86 acres (35 ha) |

| Operated by | Thames Water |

Location

The treatment works is located at grid reference TQ 359 936. It is bordered by the A1055 road and the Lea Valley Line railway to the west, Lee Valley golf course to the north, the William Girling Reservoir and the Lee Navigation to the east, and an industrial park to the south.[4]

History

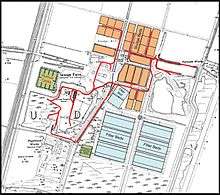

Treatment of sewage in the area began in the late nineteenth century. The 1881 Ordnance Survey map shows open fields and Deephams farm between the railway and the navigation,[5] but by 1896, housing has begun to appear. Edmonton Sewage Works was built on a site to the west of the railway, and the farm had become Edmonton sewage farm. The works included three rectangular filter beds and a large building.[6] By 1914, both facilities were owned by Edmonton Urban District, and the farm had expanded to include a large irregular-shaped filter bed.[7] Major expansion had taken place by the 1930s, with humus tanks to the west, sludge beds to the north and filter beds to the east. In the middle was a sewage pumping station, and the complex was served by a network of tramways.[8] A major expansion of the site commenced in 1939, but the onset of the Second World War resulted in the work being suspended until 1948. When work resumed, contracts were awarded to W. & C. French, Holland, Hannen & Cubitts and Marples Ridgway.[9]

In the early 1950s, the first of three parallel diffused aeration process streams was completed, which included primary and secondary treatment of the effluent. This was known as Stream A, and was followed by Stream B, completed in 1956, and Stream C, completed in 1966. By that time the site occupied an area of 86 acres (35 ha), and the works to the west of the railway had been demolished.[10] Upgrades to the infrastructure were carried out in the 1980s, when screening of storm flows was introduced, and in the 1990s, when a sludge digestion facility was built.[11] Improvements to the inlet works were again carried out in 2011/12, when the capacity of the storm storage tanks was also increased.[12] Treated effluent from the site is discharged into Salmons Brook, and the quality of this effluent has gradually improved as the works have been modified.[11] Salmons Brook flows into Pymmes Brook and subsequently into the Lee Navigation at Tottenham Lock.

The works serves a large area of north east London, both inside and outside the M25 corridor. While modern developments tend to segregate rainwater from domestic sewage, and discharge it to local watercourses, many of the sewers within the catchment of the works date from before 1936, and mix the two sources of water together, increasing the volumes that need to be handled by the works. Local sewers feed into three main gravity trunk sewers, which deliver effluent to the works. Waltham Abbey, Cheshunt, Cuffley and north east Enfield are connected to the Lee Valley Sewer. South and west Enfield, and east Barnet are served by the Barnet High Level Sewer, while the Tottenham Low Level Sewer transports sewage from Tottenham, Wood Green and south east Enfield. It is also joined by the Chingford Branch Sewer, which serves the western part of the London Borough of Waltham Forest.[13]

By 2011, the site was the fourth largest of the sewage treatment works operated by Thames Water, and served a population equivalent of 885,000. Much of the equipment was in need of renewal, and levels of suspended solids, biochemical oxygen demand and total ammonia allowed in treated effluent were to be lowered from 31 March 2017, under the terms of the Freshwater Fish Directive and the Water Framework Directive. A major reconstruction project was begun, which involved increasing the capacity of the works to cater for a population equivalent of 941,000 and a peak inlet flow of 497 Megalitres per day (Mld).[14] Because of the constrained nature of the site, consideration was given, during the design phase, to building part of the new works at a separate location. 22 sites within a 2-mile (3 km) radius of Deephams were initially identified, and these were then reduced to a short-list of five. An assessment of the whole life cost of using a separate site was then undertaken, and concluded that developing the existing site would be the best way forwards.[15] Any solution required that the works could continue to treat 209,000 tonnes of sewage per day to the existing standards while the work was progressing.[16]

Works railway

The works railway was of 2 ft (610 mm) gauge, and was constructed in the 1920s. Four diesel and two petrol locomotives were used during the life of the railway system, which closed around 1968, when the remaining three locomotives were sold on for further work elsewhere. Details of the locomotives are summarised below.[17]

| Name | Builder | Works No. | Year built | Arrangement | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unnamed | possibly Orenstein & Koppel | 4w diesel | Origins unknown. Scrapped. | ||

| unnamed | Motor Rail | 3728 | 1925 | 4w petrol | Bought new. Scrapped or sold. |

| unnamed | Hibberd | 1636 | 1930 | 4w petrol | Bought from Daniel Cornish, Shenfield and Milton Brickworks, Brentwood, 1930. Scrapped or sold. |

| No 1 | Ruston & Hornsby | 174147 | 1935 | 4w diesel | Bought from Perry Oaks Works, early 1952. Sold to M. E. Engineering, Cricklewood 1968. |

| No 2 | Motor Rail | 9711 | 1952 | 4w diesel | Bought new, but shown at a Public Works exhibition by Motor Rail first. Sold to M. E. Engineering, Cricklewood 1968. |

| No 3 | Motor Rail | 9543 | 1950 | 4w diesel | Bought new. Sold to M. E. Engineering, Cricklewood 1968. |

Two of the locomotives still exist, and have been privately preserved. Motor Rail No 2 is at Eynsford, Kent,[18] and Motor Rail No 3 is near Buxton in Derbyshire.[19]

Treatment process

Sewage arrives at the works through the three trunk sewers, which are deep underground. The effluent is therefore pumped up to the inlet works, where debris such as cloth, paper and plastic is removed. It is washed and dumped into skips, to be taken to a landfill site. Grit is also removed and washed. Some is recycled as a building material, and some goes to landfill. In storm conditions, when the incoming flow exceeds the capacity of the works, some of the sewage is passed through separate storm screens, which perform a similar process, and is stored in storm tanks until the flows reduce, and the contents of the tanks can be processed by the works.[20]

The cleared flow is passed to the primary settlement tanks, where solid material settles out onto the floor of the tank. Mechanical scrapers push this sludge into hoppers, for transfer to the sludge treatment plant. Fat and grease forms a scum on the surface of the tanks, and this is skimmed off. After a period, which allows most of the organic material to settle out, the liquor passes over weirs at the end of the settlement tanks to the secondary treatment process. This consists of aeration lanes, where air is pumped through the liquor, to encourage the growth of bacteria which are already present in the wastewater. The bacteria digest the remaining organic material which is suspended or dissolved in the water. The bacteria form an activated sludge,[21] a process developed at Davyhulme Sewage Works in Manchester by Edward Ardern, the chief chemist, and William Lockett, the chief research assistant, in 1914.[22]

The activated sludge and partially treated sewage pass on to the final settlement tanks, where the sludge settles out. Some of the sludge is fed back into the aeration lanes, to assist the start of the secondary treatment process, while some is surplus, so is dewatered and passes on to the sludge treatment process. The liquid from the final settlement tanks is of sufficient quality that it can be discharged into Salmons Brook, from where it makes its way into the Lee Navigation via Pymmes Brook. Before discharge, some of the water is passed through a tertiary treatment phase, where a fine filter is used to remove residual fine particles. The woven mesh membrane must be washed periodically to remove any accumulated sediments. Disk filters capable of treating between 40 and 50 percent of the works flow were installed in 2012, and Thames Water hoped to increase this to allow all of the flow to be filtered by 2015.[23]

Sludge and scum from the primary settlement tanks has its water content lowered, and is then stored to allow levels of bacteria and pathogens to reduce naturally. The speed of this process is increased by heating the sludge in digestion tanks, enabling bacteria to break down the structure of the sludge. This process produces biogas, which is used in a combined heat and power plant to supply some of the energy needs of the whole treatment process. The end product is a fertiliser rich in nutrients, which is used in agriculture.[24]

Bibliography

- Industrial Locomotives: including preserved and minor railway locomotives. 16EL. Melton Mowbray: Industrial Railway Society. 2012. ISBN 978 1 901556 78 0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicholls, Robert (2015). Davyhulme Sewage Works and its Railway. Narrow Gauge Railway Society. ISBN 978-0-9554326-8-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ollett, Edward (2013). Deephams STW AMP5/6 Quality Upgrade - Phase 1 (PDF). Water Treatment and Sewerage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thames (2014). "A630 Deephams Sewage Works Upgrade" (PDF). Thames Water. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waywell, Robin (2007). Industrial Railways & Locomotives of Hertfordshire and Middlesex. Industrial Railway Society. ISBN 978-1-901556-46-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- Site Site 00/43; PLK01 - Thames Valley Archaeological Services (retrieved 2011-08-29)

- Thames Water (March 2010) retrieved 2011-08-29

- From http://www.parliament.uk/

- 1:5,000 map, Streetmap, available here

- Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1881

- Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1896

- Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1914

- Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1936

- Waywell 2007, p. 158.

- Ollett 2013, p. 132.

- Thames 2014, p. 8.

- "Thames Water awards contract for Deephams Sewage Works upgrade". Working With Water. 17 March 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Thames 2014, pp. 9-10.

- Ollett 2013, p. 131.

- Ollett 2013, pp. 133,135.

- Thames 2014, p. 6.

- Waywell 2007, pp. 158-159.

- Handbook 2012, p. 111.

- Handbook 2012, p. 52.

- Thames 2014, p. 13.

- Thames 2014, pp. 13-14.

- Nicholls 2015, p. 25.

- Thames 2014, p. 14.

- Thames 2014, pp. 14-15.