Date and time notation in Canada

Date and time notation in Canada combines conventions from the United Kingdom, the United States, and France, often creating confusion.[1] The Government of Canada specifies the ISO 8601 format for all-numeric dates (YYYY-MM-DD; for example, 2020-08-17).[2] It recommends writing the time using the 24-hour clock (23:49) for maximum clarity in both English and French,[3] but also allows the 12-hour clock (11:49 p.m.) in English.[4]

| Full date | 17 August 2020 August 17, 2020 17 août 2020 |

|---|---|

| All-numeric date | 2020-08-17 |

| Time | 23:49 11:49 p.m. [refresh] |

Date

When writing the full date, English speakers vacillate between the forms inherited from the United Kingdom (day first, 7 January) and United States (month first, January 7), depending on the region and context. French speakers consistently write the date with the day first (le 7 janvier). The government endorses all these forms when using words, but only recommends the ISO format for all-numeric dates to avoid error.

English

The date can be written either with the day or the month first in Canadian English, optionally with the day of the week. For example, the seventh day of January 2016 can be written as:[5]

- Thursday, 7 January 2016 or Thursday, January 7, 2016

- 7 January 2016 or January 7, 2016

- 2016-01-07

The month-day-year sequence is the most common method of writing the full date in English, but formal letters, academic papers, and reports often prefer the day-month-year sequence.[2] Even in the United States, where the month-day-year sequence is even more prevalent, the Chicago Manual of Style recommends the day-month-year format for material that requires many full dates, since it does not require commas and has wider international recognition.[6] Writing the date in this form is also useful for bilingual comprehension, as it matches the French sequence of writing the date. Documents with an international audience, including the Canadian passport, use the day-month-year format.[7]

The date is sometimes written out in words, especially in formal documents such as contracts and invitations, following spoken forms:[2]

- "… on this the seventh day of January, two thousand and sixteen …"

- "… Thursday, the seventh of January, two thousand and sixteen …"

- informal: "… Thursday, January [the] seventh, twenty sixteen …"

French

French usage consistently places the day first when writing the full date. The standard all-numeric date format is common between English and French:[8]

- [le] jeudi 7 janvier 2016

- [le] 7 janvier 2016

- 2016-01-07

The first day of the month is written with an ordinal indicator: le 1er juillet 2017.[9]

The article le is required in prose except when including the day of the week in a date. When writing a date for administrative purposes (such as to date a document), one can write the date with or without the article.[9]

All-numeric dates

The Government of Canada recommends that all-numeric dates in both English and French use the YYYY-MM-DD format codified in ISO 8601.[10] The Standards Council of Canada also specifies this as the country's date format.[11][12]

The YYYY-MM-DD format is the only method of writing a numeric date in Canada that allows unambiguous interpretation, and the only officially recommended format.[2] The presence of the DD/MM/YY (international) and MM/DD/YY (American) formats often results in misinterpretation. Using these systems, the date 7 January 2016 could be written as either 07/01/16 or 01/07/16, which readers can also interpret as 1 July 2016 (or 1916); conversely, 2016-01-07 cannot be interpreted as another date.

In spite of its official status and broad usage, there is no binding legislation requiring the use of the YYYY-MM-DD format, and other date formats continue to appear in many contexts. For example, Payments Canada prefers ISO 8601, but allows cheques to be printed using any date format.[13] Even some government forms, such as commercial cargo manifests, offer a blank line with no guidance.[14] To remedy this, Daryl Kramp tabled a private member's bill directing courts on the interpretation of numeric dates by amending the Canada Evidence Act in 2011,[15] which would effectively outlaw all numeric date formats other than YYYY-MM-DD.[1] Todd Doherty revived this bill in 2015, but it did not progress beyond first reading before the end of the 42nd Canadian Parliament.[16][17]

Federal regulations for shelf life dates on perishable goods mandate a year/month/day format, but allow the month to be written in full, in both official languages, or with a set of standardized two-letter bilingual codes, such as 2016 JA 07 or 16 JA 07. The year is only required if the date is beyond the current year, and can be written with two or four digits.[18] These codes are occasionally found in other contexts, alongside other abbreviations specific to English or French.[19][20]

Time

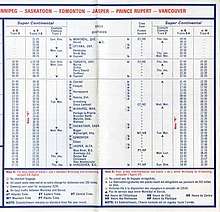

Canada was an early adopter of the 24-hour clock, which Sir Sandford Fleming promoted as key to accurate communication alongside time zones and a standard prime meridian.[21] The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) began to use it in 1886, prior to its official adoption by European countries.[22][23] The 24-hour notation is shorter, removes the potential for confusing the first and second halves of the day especially visible at midnight (00:00 or 24:00, 12:00 a.m.) and noon (12:00, 12:00 p.m.), and is language-neutral.[24] English speakers use both the 24- and 12-hour clocks, while French speakers use the 24-hour clock universally.

English

The Government of Canada recommends using the 24-hour clock to avoid ambiguity, and many industries require it. Fifteen minutes after eight o'clock at night can be written:[3]

- 20:15

- 20:15:00

- 8:15 p.m.

The 24-hour clock is widely used in contexts such as transportation, medicine, environmental services, and data transmission, "preferable for greater precision and maximum comprehension the world over".[4] Its use is mandatory in parts of the government as an element of the Federal Identity Program, especially in contexts such as signage where speakers of both English and French read the same text.[25]

The government describes the 24-hour system as "desirable" but does not enforce its use, meaning that the 12-hour clock remains common for oral and informal usage in English-speaking contexts.[26] This situation is similar to the use of the 24-hour clock in the United Kingdom.

French

Communications in Canadian French write the time using 24-hour notation for all purposes.[27] The hours and minutes can be written with different separators depending on the context:[28]

- 20 h 15

- 20:15 (tables, schedules, and other technical or bilingual uses)

References

- Sanderson, Blair (18 January 2016). "Proposed legislation aims to settle date debate". CBC News. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- Collishaw, Barbara (2002). "FAQs on Writing the Date". Terminology Update. 35 (2): 12.

- Translation Bureau, Public Works and Government Services Canada (1997). "5.13: Representation of time of day". The Canadian style: A guide to writing and editing (Rev. ed.). Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-276-6.

- Collishaw, Barbara (2002). "FAQs on Writing the Time of Day". Terminology Update. 35 (3): 11.

- Translation Bureau, Public Works and Government Services Canada (1997). "5.14: Dates". The Canadian style: A guide to writing and editing (Rev. ed.). Toronto: Dundurn Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-55002-276-6.

- "6.38: Commas with dates". The Chicago manual of style (17 ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 2017. ISBN 978-0-226-28705-8.

- "Transportation company obligations: Guide for transporters". Canada Border Services Agency. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Bureau de la traduction, Travaux publics et Services gouvernementaux Canada (15 October 2015). "Date : ordre des éléments (Recommandation linguistique du Bureau de la traduction)". TERMIUM Plus: Clefs du français pratique (in French). Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Bureau de la traduction, Travaux publics et Services gouvernementaux Canada (15 October 2015). "Date (règles d'écriture)". TERMIUM Plus: Clefs du français pratique (in French). Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- "TBITS 36: All-Numeric Representation of Dates and Times – Implementation Criteria". Treasury Board of Canada. 18 December 1997. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- National Standard of Canada, "CAN/CSA-Z234.4-89 (R2007): All-Numeric Dates and Times". Standards Council of Canada. 31 December 1989. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Getting on the Same Page When It Comes to Date and Time". Standards Council of Canada. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Cheque Specifications" (PDF). Canadian Payments Association. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- Blaze Carlson, Kathryn (29 October 2011). "Is 02/04/12 February 4, or April 2? Bill seeks to end date confusion". National Post. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- House of Commons of Canada (13 June 2011). "Private Member's Bill C-207 (41-2): An Act to amend the Canada Evidence Act (interpretation of numerical dates)". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- House of Commons of Canada (10 December 2015). "Private Member's Bill C-208 (42-1): An Act to amend the Canada Evidence Act (interpretation of numerical dates)". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Hannay, Chris (1 January 2016). "Tory MP's bill seeks to clarify how dates are written in legal proceedings". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Food Labelling and Claims Directorate (8 June 2017). "Date markings and storage instructions". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Government of Canada. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Office québécois de la langue française (2002). "Abréviations des noms de mois". Banque de dépannage linguistique (in French). Gouvernement du Québec. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Bureau de la traduction, Travaux publics et Services gouvernementaux Canada (15 October 2015). "Mois". TERMIUM Plus: Clefs du français pratique (in French). Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Creet, Mario (1990). "Sandford Fleming and Universal Time". Scientia Canadensis: Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine. 14 (1–2): 66–89. doi:10.7202/800302ar.

- Fleming, Sandford (1886). "Time-reckoning for the twentieth century". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (1): 345–366. Reprinted, 1889: Time-reckoning for the twentieth century at the Internet Archive.

- The Times notes the CPR timetable in 24-hour notation on a trip from Port Arthur, Ontario: "A Canadian tour". The Times (31880). London. 2 October 1886. col 1–2, p. 8.

- Kuhn, Markus (19 December 2004). "International standard date and time notation". University of Cambridge Department of Computer Science and Technology. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (August 1990). Federal Identity Program Manual.

- Public Works and Government Services Canada (15 October 2015). "time of day, elapsed time". TERMIUM Plus: Writing Tips. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Ministre des approvisionnements et services Canada (1987). "1.1.12 Heure, minute, seconde". Guide du rédacteur de l'administration fédérale (in French). Ottawa. ISBN 978-0-660-91030-7.

- Bureau de la traduction, Travaux publics et Services gouvernementaux Canada (15 October 2015). "Heure (écriture de l'heure)". TERMIUM Plus: Clefs du français pratique (in French). Retrieved 19 July 2018.

.svg.png)