Danish March

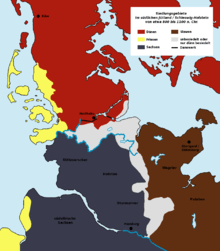

The terms Danish March and March of Schleswig (German: Dänische Mark or Mark Schleswig) are used to refer to a territory in modern-day Schleswig-Holstein north of the Eider and south of the Danevirke. It was established in the early Middle Ages as a March of the Frankish Empire to defend against the Danes. The term "Danish March" is a modern designation not found in mediaeval sources. According to the Royal Frankish Annals the Danish King led his troops "into the March" in 828 (ad marcam). In the 852 Yearbook of Fulda there is mention of a "Guardian of the Danish Border" (custodes Danici limitis).

In Old Norse, Denmark was called Danmǫrk, viz. the marches of the Danes. The Latin name is Dania.

Carolingians

Charlemagne is believed to have established a Danish March around 810 CE, following rulership claims by the ambitious Danish King Gudfred over the territory north of the Elbe, which was at the time part of Saxony and which Charlemagne had recently subjugated.[1] The duration and extent of the Carolingian march is however uncertain. In 811 it was agreed that the Eider would mark the Danish southern border. However, in the Royal Frankish Annals of 828 it was recorded that the Danes crossed into the "March" and crossed the Eider, the formulation of which raises the possibility that the Carolingian march lay to the north of the Eider.

In Wigmodi (a Gau which lay between the mouths of the Elbe and the Weser) and in Nordalbingia (north of the Elbe) the Saxons had resisted Charlemagne for the longest. Many of the rebelling Nordalbingians were deported to the interior of the Frankish Empire in 795 and especially 804 with their lands initially being left to the Slavic Obotrites to act as a buffer between the Franks and the Danes. After the Obotrites were forced to become Danish tributaries in 808, the Franks crossed the Elbe again and according to the Royal Frankish Annals began construction of Esesfeld Castle on 15 March 809.

After Gudfred was murdered in 810 as a result of internal power struggles, his successor Hemming negotiated peace with the Frankish Empire, and established the Eider as the border. In 817 the Danes and Obotrites unsuccessfully besieged the fortifications at Esesfeld. Until 822 Frankish border Counts are testified, but their influence presumably did not extend beyond Esesfeld. The Franks probably could not hold the castle, leading them to build the Delbende on the Elbe in 822, followed by Hammaburg around 825.

Ottonians

The first Saxon King of Germany/East Francia Henry the Fowler won an important victory over the Danes in 934 (931 or 936 in some sources). Adam von Bremen reported that it was in this context that a Margrave was first enthroned in the important trade centre of Haithabu on the Schlei and the settlement of Saxons. It is therefore widely believed that Henry added the territory between the Eider and Schlei to his kingdom as a march. His son Otto I founded the Bishopric of Schleswig in 948. In 974 a Danish uprising took place and the Margrave was killed, but shortly thereafter Duke Bernard I of Saxony and Count Henry I of Harsefeld/Stade pushed them back. The Danes succeeded in pushing the border back to the Eider during the Slavic revolts of 983. Initially the border remained, but was continually fought over.

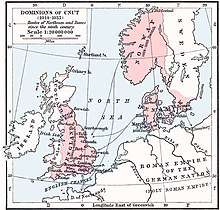

In 1025 Cnut the Great's daughter Gunhild was betrothed to the son of Emperor Conrad II, the future Emperor Henry III. As part of the dowry, Cnut was recognised as overlord of all of southern Jutland up to the Eider, thus putting an end to the march. (The marriage took place in 1036.)

The former Danish territory of Fræzlæt, an administrative division of Schleswig, covered an area nearly identical to that of the Danish March.

Sources

- Einhard (1997). Vita Caroli Magni/Das Leben Karls des Großen. Stuttgart: Reclam.

- Fleckenstein, Josef (1967). Karl der Große. Göttingen.

- Hägermann, Dieter (2003). Karl der Große. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt. ISBN 3-499-50653-X.

- Riis, Thomas (2001). Düwel, Klaus; Marold, Edith; Zimmermann, Christine (eds.). "Vom Land "synnan aa" bis zum Herzogtum Schleswig". Von Thorsberg nach Schleswig. Sprache und Schriftlichkeit eines Grenzgebietes im Wandel eines Jahrtausends. Berlin / New York: 53–60.

- Klapheck, Thomas (2008). "2.4.3 Die Entwicklung Transalbingiens bis zur Zeit Ansgars". Der heilige Ansgar und die karolingische Nordmission. Diss. phil. Oldenburg, Verlag Hahnsche Buchhandlung Hannover. pp. 88–95.

References

- Dieter Hägermann: Karl der Große. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2003, p44.