Daniel Pabst

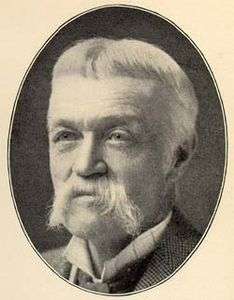

Daniel Pabst (June 11, 1826 – July 15, 1910) was a German-born American cabinetmaker of the Victorian Era. He is credited with some of the most extraordinary custom interiors and hand-crafted furniture in the United States. Sometimes working in collaboration with architect Frank Furness (1839–1912), he made pieces in the Renaissance Revival, Neo-Grec, Modern Gothic, and Colonial Revival styles. Examples of his work are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[1] the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Daniel Pabst | |

|---|---|

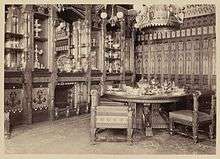

Dining room of the Theodore Roosevelt Sr. house in New York City (1873, demolished). | |

| Born | June 11, 1826 Langenstein, Hesse, Germany |

| Died | July 15, 1910 (aged 84) Philadelphia |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Cabinetmaker |

| Known for | Collaboration with Frank Furness Glenview Mansion interiors Emlen Physick House interiors Modern Gothic cabinet (Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

Background

Born in Langenstein, Hesse, Germany, Pabst immigrated to the U.S. in 1849 and settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he would make his professional career. The excellence of his craftsmanship elevated him above his peers, as did the strongly architectonic (building-like) quality of his furniture designs—often massively scaled, with columns, pilasters, rounded and Gothic arches, bold carving and polychromatic decoration. He was a master at cameo-carving (intaglio) in wood – veneering a light-colored wood over a darker, then carving through to create a vivid contrast. Some pieces were adorned with decorative tiles, others with painted glass panels backed with reflective foil. Elaborate strap hinges and hardware were commonly used, and sometimes the furniture was ebonized. His Philadelphia shop grew to employ up to 50 workmen,[2] but the company's records do not survive. Of the presumably thousands of pieces produced by his shop over half a century, only two are signed,[upper-alpha 1] and very few are documented.[upper-alpha 2] Therefore, identification of his works must be done through attribution.[5]

With Furness

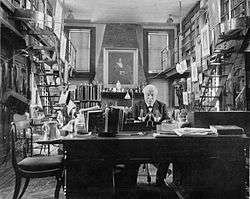

The most famous pieces attributed to Pabst are a Neo-Grec desk and chair made to the designs of Frank Furness. Created for the architect's brother Horace (and slightly altered from Frank's surviving drawings), they are now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[7] Furness family papers document a set of bookcases created by the pair – "These bookcases were placed in position this day—February 18th 1871. They were designed by Capt. Frank Furness, and made by Daniel Pabst …"[8] The bookcases are visible in a circa-1900 photograph of Horace Howard Furness's library.[9] One of them is now at the University of Pennsylvania, others are now in the Barrie & Deedee Wigmore collection in New York City.[10] A circa-1870 Neo-Grec armchair from Horace Howard Furness's city house, designed by Frank Furness and attributed to Pabst, was exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston in 1987.[11]

The newly formed architectural firm of Furness & Hewitt won the design competition for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1871–76). The Philadelphia art-museum-and-school's original furnishings included a lectern, bookcases, and set of Neo-Grec furniture for the boardroom.[12] Armchairs from the set, attributed to Furness and Pabst, are in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania.

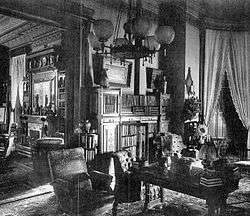

A director of the Academy, liquor baron Henry C. Gibson, hired Furness & Hewitt to redecorate his Greek Revival city house.[13] The eye-popping Moorish and Neo-Grec interiors are attributed to Furness, and may have been made by Pabst.[upper-alpha 3][15] Gibson appears to have used copies of the PAFA armchairs as seating in his picture gallery.[16] His Neo-Grec library table – now at the Detroit Institute of Arts – is attributed to Furness and Pabst.[17][18]

Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. (father of the future president) hired Furness to decorate his newly built townhouse at 6 West 57th Street, New York City (demolished). The ornate Neo-Grec paneling, bookcases, cabinetry and mantels are based on designs in Furness's sketchbook,[19] and their manufacture is attributed to Pabst. The pair is also credited with individual pieces of Roosevelt furniture.[20] The massive dining table – with a base featuring carved herons pinching frogs in their bills – is now in the collection of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia. The cameo-carved master bedroom suite is now at Sagamore Hill National Historic Site, President Theodore Roosevelt's summer home in Oyster Bay, New York.[21] The Neo-Grec case for the Roosevelts' upright piano (with cameo-carved panels) and their library table (with oversized Corinthian capitals) are unlocated.[20] The late antiques expert/dealer Robert Edwards[22] – who discovered the Pabst-attributed cabinets now at the Brooklyn Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art – identified a Neo-Grec side chair (now in the Barrie & Deedee Wigmore collection) as having come from the Roosevelt library.[10]

A 17-year-old architecture student visiting Philadelphia in June 1873, Louis Sullivan, closely examined a house nearing completion at 510 South Broad Street, and decided that he was going to work for the firm that designed it. The next day he presented himself to Frank Furness, and was hired as a draftsman at US$10 a week.[23] The Bloomfield H. Moore House was the most ambitious Furness & Hewitt domestic commission to date, and Furness's interiors – manufacture attributed to Pabst – were his most perverse.[10] The egrets from the Roosevelt dining table reappeared, this time supporting the dining room mantel, but the house is best remembered for the nightmarish chimneypiece in its library.[24] The tall and massive walnut chimneypiece featured compressed columns supporting oversized piers incised with stylized sunflowers, twin "hounds of hell" grotesques snarling from behind shields, a diapered and gold-leafed tympanum bisected by a center column, a crocketed pediment rising to a finial, and twin owls staring down from the roof. The Moore house was demolished in the 1950s, but much of the chimneypiece, stripped of its grotesques and thus about 3 feet (0.91 m) shorter, survives.[25][upper-alpha 4] Sullivan went on to lead the Chicago School of Architecture, and become the mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright.

An 8-foot (2.4 m)-tall Modern Gothic exhibition cabinet now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is attributed to Pabst, and was once attributed also to Furness.[27] It features cameo-carved doors in maple and walnut, painted glass panels backed with foil, a shingled-roof top, and ornate brass hardware. This tour de force piece is reminiscent of Furness's bank buildings of the late-1870s, although recent scholarship discounts Furness's participation in its design.[upper-alpha 5]

Without Furness

Pabst created masterworks without Furness. He received a medal for excellence at the 1876 Centennial Exposition for a large walnut sideboard (whereabouts unknown):[29]

The most prominent object of the class was a black-walnut sideboard designed and made by Daniel Pabst of Philadelphia. The treatment was rather architectural throughout, too much so for practical purposes. Such a heavy piece should be built in a house, and not be treated as movable furniture. The wood was filled and highly polished on shellac, as is the common practice of our cabinet-makers with their best work … The hinges and metallic mountings were of oxidized silver of the finest workmanship and spirited in design. All the panels were filled with relief-carving, animal and floral forms being introduced; but these were not all of original design. A noticeable feature was the central mirror surmounted by a crocketed gable, richly carved, with finial composed of two birds resembling pelicans. Four finials on the posts which defined the three main divisions were finished with carved cockatoos. The amount of rich carving far surpassed that on any other Gothic piece in the Exhibition...[30]

Pabst's "largest existing work" is thought to be the John Bond Trevor mansion, "Glenview" (1876–77), in Yonkers, New York[31]—part of the Hudson River Museum complex.[32] An 1877 newspaper article credits the mansion's mantels to Pabst;[upper-alpha 6] and the interior woodwork, ebonized library, and grand staircase are attributed to him.[upper-alpha 7] Although there is no evidence of Furness's involvement, Pabst used design elements that can also be found in Furness commissions—the parlor's mantel features the dog-faced beasts that flank fireplaces in several Furness houses,[35] the entrance hall features door frames and a chimneypiece with shingled roofs (a frequent Furness motif). The 1877 article specifically credits the dining room's "very elaborate buffet" to Pabst,[upper-alpha 8] although only its base survives. Its relief-carved fox-and-crane panels,[36] copied from a plate in Charles Eastlake’s book Hints on Household Taste,[37] are repeated on the sideboard at the Art Institute of Chicago, and on other attributed pieces.[upper-alpha 9]

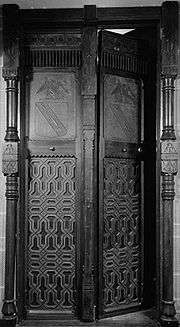

Pabst also worked with Furness's competitors. The firm of Collins & Autenrieth designed the Charles T. Parry House (1870–71) at 1921–27 Arch Street, Philadelphia,[39] and its Renaissance Revival interior woodwork is attributed to Pabst.[40] The paneled vestibule, while still attributed to Pabst, may date from a later renovation by another firm, Wilson Brothers & Company.[upper-alpha 10] The house's second owner was the renowned surgeon and teacher, Dr. David Hayes Agnew – subject of the 1889 Thomas Eakins painting, The Agnew Clinic. Before it was demolished in 1968, the house was documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.[42] The paneled vestibule, mirrors and other interior woodwork were salvaged and donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[43]

Joseph M. Wilson (of Wilson Brothers) was hired by Col. Joseph D. Potts to remodel a circa-1850 suburban house at 3905 Spruce Street, Philadelphia.[44] And remodel it Wilson did, designing numerous additions – including a 4-story tower – and unifying the exterior with polychromatic diamond-patterned brickwork. The Potts House (altered 1875–76)[45] seems to have been strongly influenced by Furness's work,[46] and has over-the-top Neo-Grec interiors that may be by Pabst.[47] The dog-faced beasts appear again, flanking a fireplace, only this time they have wings! The Potts House barely escaped demolition in the late 1960s, when the University of Pennsylvania razed several city blocks to expand. From 1970 to 2005, it housed the university's radio station, WXPN. Now called "Wayne Hall," it houses the University of Pennsylvania Press.[48]

Several sets of glass-doored bookcases attributed to Pabst exist—including a Modern Gothic 10-bookcase set (with shingled roofs), matching mantel (with dog-faced beasts) and overmantel mirror, that may have been part of a Furness commission.[49] Pabst is credited with the elaborate, two-story interior of medieval scholar Henry Charles Lea's private library (1881).[50] This was removed from Lea's house at 2000 Walnut Street, Philadelphia in 1925, and installed at the University of Pennsylvania. When it was re-installed at Van Pelt Library in 1962, the fireplace was moved from one of the long walls to a short wall.

| External video | |

|---|---|

The "Baby Doe" Tabor bedroom suite – a massive, intricately carved bed and bureau that once belonged to Senator Horace Tabor of Colorado – is attributed to Pabst.[52] Tabor was sworn in as a U.S. senator on January 27, 1883, but was only a temporary placeholder, serving 37 days in office until the Colorado legislature could fill the vacancy. Three days before resigning he married his paramour, Elizabeth "Baby Doe" McCourt, in Washington, D.C. The bedroom suite was reputedly purchased just before or during their honeymoon, and returned with them to Colorado. The bed's 8-foot-8-inch (2.64 m)-tall headboard is carved with owls and bats, creatures of the night; the 8-foot-11-inch (2.72 m)-tall bureau-and-mirror is carved with cockatoos and songbirds, creatures of the day. The suite was later owned by publisher William Randolph Hearst, and was part of the furnishings of "Hearst Castle" in San Simeon, California. The Tabors' rags-to-riches-to-rags saga became the basis for the 1932 film Silver Dollar and the 1956 opera The Ballad of Baby Doe. Following six years on the antiques market – including a stint on eBay[53] – the "Baby Doe" Tabor bedroom suite was acquired by History Colorado, and is now part of the permanent collection of its museum in Denver.[54]

Business

Pabst formed a partnership with Franz Krausz (Krauss) about 1854. According to Philadelphia directories, Pabst was located at 222 South 4th Street, circa 1854–56; Pabst and Franz Krausz were listed as cabinetmakers at 90 Cherry Street, circa 1855–57; both were working at 600 Cherry Street and residing at 234 Stamper's Alley in Philadelphia, circa 1858; the shop moved to 120 Exchange Place, circa 1861; and the company was listed under the name "Pabst and Krauss," circa 1866.[55]

According to Philadelphia land records, Daniel Pabst and Franz Krauss, both cabinetmakers of the City of Philadelphia, purchased the property at 269 South Fifth Street on February 16, 1865 for the sum of US$4,500 ($75,200 today).[56]

A company profile from 1886:

Daniel Pabst, Designer and Manufacturer of Artistic Furniture, No. 269 South Fifth Street—One of the leading and most successful designers and manufacturers of artistic furniture in Philadelphia is Mr. Daniel Pabst, whose office and manufactory are located at No. 269 South Fifth Street. The business was established in 1854 by Pabst & Krauss,[57] who were pioneers in the trade here. About 16 years ago Mr. Pabst became sole proprietor. The premises are very spacious, admirably arranged, and equipped throughout with every facility and convenience for the transaction of business, employment being given to 25 skilled workmen. Mr. Pabst designs and manufactures art and antique furniture of all kinds, which, for beauty and originality of design, superior and elaborate finish are unexcelled. The trade of the house extends through this and adjacent States. It is so well known and has retained its old customers for so long a time, that its reputation for honorable, straightforward dealing is established beyond the requirements of praise.[58]

Late in life, Pabst made a list from memory of his customers.[upper-alpha 11] It included prominent Philadelphians such as John Christian Bullitt, Henry Disston, John M. Doyle, Horace Howard Furness, Charles Custis Harrison, Thomas J. McKean, C. B. Newbold, Charles T. Parry, George B. Preston, John Lowber Welsh, Wistar [Caspar Wister?], John Wyeth; New Yorker Theodore Roosevelt, Sr.; and the Pennsylvania Railroad.[upper-alpha 12]

On his business card – undated (no earlier than 1865, from the address) – Pabst listed "Gothic church furniture a specialty."[61] So there may remain numerous as-yet-unidentified pulpits, pews and altars created by his shop.[62][63]

Personal

A year after his emigration to the United States, Pabst married Helena "Salina" Gross (1831–1912) in Philadelphia, on June 11, 1850. As a wedding gift, he made her an exquisite mahogany sewing box – its inscription, written in a mixture of German and English, concludes: "Remember me Salina Gross 1850."[64] Of the couple's seven children, only three lived to adulthood: Emma, Laura and William.[3] William Pabst worked in his father's shop, and was listed as a partner in 1894.[65]

Pabst was active in Philadelphia's large German-American community, and sponsored other emigrants, "taking them into his household while they were studying and learning their way in the new country."[66] He was a member of the German Society of Pennsylvania, which published poems by him. He saw his heritage as integral to his success: "I brought all of Germany here with me, in my inward eye. The tall towers of Cologne, the wonders of Frankfurt-on-Main, the old grey castles perched in mid-air along the Rhine—they were all part of my work."[67]

He retired in 1896 at age 70, but continued making furniture for friends and family members into his 80s.[68] In June 1910, he was honored by the University of Pennsylvania for 50 years of carving large decorative spoons for senior-class "Honor Men Awards."[69] Several of the spoons survive, including one in the collection of the Pabst family.

Pabst died in Philadelphia on July 15, 1910. He and his wife are buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery, outside Philadelphia.[70]

Legacy

Scholarship on Daniel Pabst rests on the foundational research begun in the early 1930s by Philadelphia Museum of Art curator of decorative arts Calvin Hathaway. Utilizing the Pabst customer list, provided by the cabinetmaker's daughter Emma Pabst Reisser, Hathaway tracked down furniture still owned by the customers' descendants. The Lea dining room suite and music cabinet, the Ingersoll cabinets, and several other pieces were loaned to PMA for a 1933 exhibition on Victorian art and decorative arts.[71] Some pieces were later donated to the museum.[72]

The largest collection of Pabst furniture is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In addition to the above museums, he is represented in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Brooklyn Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York, the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Delaware, and elsewhere.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art hosted a study day on Pabst in October 2008, organized by Jennifer Zwilling, and is preparing a comprehensive exhibition of his work.[10] (The exhibition was put on hold in 2010. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has the largest institutional holdings of Pabst's work). A great-grandson, Richard Pabst, is assembling a complete list of his known and attributed works.[73]

Assessment

The mark of a great cabinetmaker is his combination of design and execution. It's how well they resolve the challenges of designing a piece coupled with their craftsmanship and technique. Pabst was the most distinguished cabinetmaker in Philadelphia in the last quarter of the 19th century. Clearly, the quality of his carving and cabinetmaking is of the highest order, and Philadelphia has a tradition of producing superior furniture since the 18th century, overshadowing Boston and New York.

Daniel Pabst really did develop a unique and identifiable decorative vocabulary. He tended to envelop the object's architecture with a fine scale pattern; it was an invention of his own. He wasn't aping the European antecedent. While I think there are masterpieces of Pabst's not from Furness's pen, he certainly benefitted from his close association with the architect.

Pabst's Modern Gothic work presents the very germ of the modern movement. Like Christopher Dresser and Bruce Talbert, he conventionalized design, departing from the realistic motifs of the mid-19th century. You can see where this reductivity evolves into the Craftsman style.

— Andrew Van Styn, furniture scholar & dealer.[74]

Examples of his work

- Renaissance Revival sideboard (c. 1860s), deaccessioned from Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, private collection.[75]

- Renaissance Revival music cabinet (c. 1865–70), made for Beauveau Borie,[76] deaccessioned from High Museum of Art, private collection.[77]

- Pair of Renaissance Revival sideboards (c. 1869), made for Henry Pratt McKean and Thomas J. McKean, private collections.[78]

- Renaissance Revival sideboard (c. 1870), Biggs Museum of American Art, Dover, Delaware.[79]

- Neo-Grec library table (c. 1870), design attributed to Frank Furness, made for Henry C. Gibson, Detroit Institute of Arts.[18]

- Ebonized pedestal (c. 1870), Cleveland Museum of Art.[80]

- "Fox and Crane" sideboard (c. 1870–80), Art Institute of Chicago.[81]

- Furness-Pabst bookcases (1870–71), made for the city house of Horace Howard Furness, one bookcase is at the University of Pennsylvania, the rest are in private collections.

- Neo-Grec armchair (c. 1871), made for the city house of Horace Howard Furness, private collection.[11]

- Neo-Grec armchair (1871–76), made for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, design attributed to Frank Furness, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.[82] Another armchair from the set is at the Allentown Art Museum.[83]

- Neo-Grec dining table (1873), designed by Frank Furness, made for Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia.[84]

- Neo-Grec bedroom suite – bed, armoire, table, 2 chairs, settee – (1873), made for Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., Sagamore Hill National Historic Site, Oyster Bay, New York.[85]

- Neo-Grec side chair, (1873), made for the library of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., private collection.

- Modern Gothic pedestal (c. 1875), design attributed to Frank Furness, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[86]

- Modern Gothic exhibition cabinet (c. 1875), Brooklyn Museum.[87] It has a fragment of a handwritten label that may have originally read "Pabst" and "Philadelphia."

- Modern Gothic exhibition cabinet (c. 1875), Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, New York.[88]

- Modern Gothic smokers cabinet (c. 1875), private collection.[89]

- Modern Gothic Campeche-style chair (c. 1875–80), design attributed to Furness, private collection.

- Ebonized fire screen (c. 1875-95) – sold at Christie's New York, October 14, 1999 – private collection.[90]

- Modern Gothic cabinetwork & furniture (1876–77), Glenview Mansion, Yonkers, New York:

- Entrance hall: paneling, ebonized columns, shingled-roof door frames, mantel.[91] The shingled-roof overmantel is a re-creation.[92]

- Staircase.[93][3]

- Library: ebonized chimneypiece & bookcases.[94]

- Sitting room: 2 cameo-carved maple exhibition cabinets.[95]

- Parlor: mantel (with dog-faced beasts).[96]

- Dining room: "Fox and Crane" buffet base.[97] The black walnut mantel, described as "massive" in 1877, was removed in the 1930s.[92]

- Modern Gothic exhibition cabinet (c. 1877–80), Metropolitan Museum of Art.[1]

- Social Arts Club mantel & furniture – library table, console, chairs, map case – (1878), designed by Frank Furness.[98] Renamed the Rittenhouse Club, it sold the clubhouse in the 1990s,[99] and auctioned off the mantel and furniture.[100]

- Emlen Physick House (1878), Cape May, New Jersey.[101][102] Furness designed (and Pabst likely made) the interior woodwork, and 2 bedroom suites original to the house.[103][104] The cartouche on one bed's headboard is repeated in a stained glass window.[105]

- Pair of Modern Gothic pedestals (c. 1880), deaccessioned from Newark Museum, private collection.[106]

- Ebonized chair (c. 1880), Brooklyn Museum.[107]

- Modern Gothic maple bedroom suite (c. 1880) – bed, bureau with mirror, nightstand, armchair – private collection.[108]

- "Baby Doe" Tabor bedroom suite (c. 1882–83) – bed, bureau with mirror – History Colorado Center, Denver.[54]

- Colonial Revival desk (1901), exhibited at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, whereabouts unknown.[109]

Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Hanging cabinet (1860–70).[110]

- Pair of Renaissance Revival exhibition cabinets (1865–70), made for Edward Ingersoll.[111]

- Renaissance Revival mirror and console table (1866–76), made for Charles T. Parry.[112]

- Renaissance Revival dining room suite – sideboard, table, 2 armchairs, 10 sidechairs – (1868–70), made for Henry Charles Lea.

- Renaissance Revival music cabinet (1868–70), made for Henry Charles Lea.[113]

- Pier mirror (1870–71), made for Charles T. Parry.[114]

- Charles T. Parry House vestibule paneling. This either was original to the house and dates from 1870–71, or dates from a pre-1885 renovation.[43]

- Neo-Grec desk and chair (1870–71), designed by Frank Furness, made for Horace Howard Furness.[115][116]

- Neo-Grec highchair (1870–80). The highchair's crest is related to the crest on the "Fox and Crane" sideboard at the Art Institute of Chicago.[10]

- Neo-Grec partners desk (1870–90).[117]

- Modern Gothic bedroom suite – bed, bureau with mirror, nightstand – (1878), made for his daughter, Emma Pabst Reisser, two additional pieces are owned by her descendants.[118]

- Modern Gothic tall case clock (1884).[119] Signed and dated: "Daniel Pabst, Artist / 1884." One of only two known pieces signed by Pabst.

University of Pennsylvania

- Honor Men Awards (1861–1910). An ornate spoon is jokingly awarded each year to the most-popular member of the senior class. Pabst carved these spoons for fifty years.

- Furness-Pabst bookcase (1870–71), made for Horace Howard Furness.[120] Other bookcases and a pair of cabinet doors from the set are in private collections.

- Joseph D. Potts House, interior woodwork (1876), Wilson Brothers & Company, architects.

- Henry Charles Lea Library (1881).[121] Removed from 2000 Walnut Street, Philadelphia in 1925; now installed in Van Pelt Library.[122]

Winterthur Museum

- Neo-Grec D-shaped pedestal desk (c. 1870). The carving is similar to that on the Borie music cabinet.

- Modern Gothic bedroom suite (c. 1870) – bed, bureau, armoire, nightstand, 2 chairs – made for Henry Pratt McKean.[123]

- Modern Gothic vanity with mirror.[124]

- Modern Gothic drop-front music portfolio.[125]

Henry C. Gibson drawing room (decorated c. 1870, demolished), Furness & Hewitt, architects. The Neo-Grec library table (foreground) is now at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Henry C. Gibson drawing room (decorated c. 1870, demolished), Furness & Hewitt, architects. The Neo-Grec library table (foreground) is now at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Neo-Grec armchair (c.1870-75), attributed to Pabst, private collection

Neo-Grec armchair (c.1870-75), attributed to Pabst, private collection Charles T. Parry vestibule (c. 1870–84), now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Charles T. Parry vestibule (c. 1870–84), now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Bloomfield H. Moore library (1872–74, demolished 1950s), Furness & Hewitt, architects. The chimneypiece is now at a California winery.

Bloomfield H. Moore library (1872–74, demolished 1950s), Furness & Hewitt, architects. The chimneypiece is now at a California winery. Modern Gothic Campeche-style chair (c. 1875–80), attributed to Furness and Pabst, private collection.

Modern Gothic Campeche-style chair (c. 1875–80), attributed to Furness and Pabst, private collection. Joseph D. Potts staircase (1876), Wilson Brothers & Company, architects.

Joseph D. Potts staircase (1876), Wilson Brothers & Company, architects. Emlen Physick sitting room mantel (1878), Frank Furness, architect.

Emlen Physick sitting room mantel (1878), Frank Furness, architect. "Designs for Two Mantelpieces" (July 1887). One of the few surviving drawings by Pabst.

"Designs for Two Mantelpieces" (July 1887). One of the few surviving drawings by Pabst.

References

Notes

- The two signed pieces are a mahogany sewing box (Pabst's 1850 wedding gift to his bride, Helena Gross), private collection; and an 1884 Modern Gothic tall case clock at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[3]

- The documented pieces are the Furness-Pabst bookcases (Pabst is credited in an 1871 Furness letter); and the mantels and sideboard at "Glenview" (Pabst is credited in an 1877 Yonkers newspaper article). The Modern Gothic exhibition cabinet at the Brooklyn Museum has a fragment of a handwritten label that may have originally read "Pabst" and "Philadelphia."[4]

- "Furness and Hewitt drenched the interior of the Gibson house in sybaritic splendor, making it look rather like an extended Moorish smoking room. Each cabinet was distinguished by cusped horseshoe arches and geometric wood screens, behind which tantalizing vistas beckoned. Even the furniture was designed with an eye toward the ensemble, so that leonine heads guarded the table and roared beneath the fireplace mantel. The effect was dazzling—as if the Alhambra had been smuggled into one of William Penn's orderly streets."[14]

- The Bloomfield Moore chimneypiece has been restored, replacement grotesques carved, and it is now installed in a California winery.[26]

- "David Barquist, curator of American decorative arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, … agreed with [the late] Catherine Voorsanger, [associate curator of American decorative arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,] that the Pabst cabinet at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, illustrated on the cover of the 1986 catalog In Pursuit of Beauty, although once attributed to Furness does not show Furness’s hand."[28]

- "The contract for the mason work was awarded to J. & G. Stewart; for the carpenter work to S. F. Quick; the plumbing, which is very extensive and thorough, was done by the day by J. J. Coffey; the mantels were furnished by Daniel Pabst, of Philadelphia; the decorative painting was executed by Leissner & Louis, of New York; the plain painting by John McLain, of this city."[33]

- "Our attribution is based on an August 3, 1877, Yonkers Statesman article, that says the mantels and the buffet are by Pabst. No other woodworkers are mentioned and so the attribution of the rest of the house is stylistic." — Laura Vookles, Curator of Collections, Hudson River Museum.[34]

- "The dining room is trimmed with black walnut. A very elaborate buffet, made by Pabst, is built into an alcove opposite the massive mantel."[33]

- The fox-and-crane panels appear on a third sideboard, and on a wine cabinet owned by a Pabst descendant.[38]

- The 1885 Wilson Brothers catalogue lists "alterations and additions" to the Parry house, but does not give details or list a date.[41]

- A copy of the Pabst customer list is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[59]

- Bullitt, Furness, Harrison, McKean, Preston, Welsh, Wister, Roosevelt, and the Pennsylvania Railroad were all Frank Furness clients.[60]

Citations

- "Cabinet, attributed to Daniel Pabst". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2014. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- Burke 1986, p. 460.

- Hanks & Talbott 1977, pp. 8-9.

- Fragment of label, from Brooklyn Museum.

- Hanks 1982, p. 37.

- "Interior, General View Showing Width of Room, H.H. Furness Seated at Desk – Lindenshade, Library, Furness Lane, Wallingford, Delaware County, PA". Library of Congress. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Historic American Buildings Survey PA.23-WALF.2A-5

- Sewell 1976, pp. 378-79, 401-03.

- Hanks 1982, quoted in page 43.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 166–67.

- Edwards 2008.

- Kaplan & MFAB 1987, p. 73-74.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 161.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 157–59.

- Lewis 2001, p. 85.

- Henry C. Gibson interiors, from Wikimedia Commons.

- Gibson dining room, with picture gallery beyond. from Wikimedia Commons.

- Hanks 1983, pp. 263–64.

- Henry Clay Gibson Library Table, from Detroit Institute of Arts.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 181.

- Theodore Roosevelt furniture, from Furnesque on Tumblr.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 180–83.

- Robert Edwards Collection, from Winterthur Library.

- Sullivan 1924, pp. 190–92.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 168–69.

- Bloomfield Moore chimneypiece in 2009, nos. 257 & 258, from Oley Valley Architectural Antiques.

- "Berghold Estate Winery owner blends historical art with business," (image #5), Lodi News-Sentinel, January 22, 2015.

- Burke 1986, pp. 460-61.

- Solis-Cohen 2014.

- Centennial medal won by Pabst, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- American Architect and Building News 1877, p. 4.

- Cooper 2007, p. 59.

- Panetta 2006, p. 152.

- The Yonkers Statesman, August 3, 1877.

- Cooper 2007, quoted in page 59.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 169, 250, 261, 265.

- Madigan 1973, cover, plate 10.

- Eastlake 1872, plate XIII.

- Fox and Crane sideboard, from Live Auctioneers.

- Charles T. Parry House, from Philadelphia Architects and Buildings.

- Charles T. Parry House, from Wikimedia Commons.

- Wilson Brothers & Co. 1885, p. 9.

- Charles T. Parry House, from HABS.

- Zwilling 2012, pp. 44–57.

- Wilson Brothers & Co. 1885, p. 7. illustrations, p. 21.

- Potts Residence, from Philadelphia Architects and Buildings.

- Thomas & Brownlee 2000, pp. 326-28.

- Joseph D. Potts House, from Wikimedia Commons.

- Joseph D. Potts House, from University of Pennsylvania.

- Iams 2002.

- Henry Charles Lea Library, from University of Pennsylvania.

- "Tabor Bed and Dresser". History Colorado. February 27, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- Baby Doe Tabor bedroom suite, from The Magazine Antiques.

- Daniel Pabst "Baby Doe" Tabor Bedroom Set, from Rare Victorian.

- "Tabor Bed and Dresser," from History Colorado.

- McElroy's Philadelphia City Directory, Years 1856, 1857, 1858, 1861, 1866.

- Philadelphia Land Records – Recorded LRB Book 74 Page 491

- McElroy's Philadelphia City Directory of 1866

- "Philadelphia: Leading Merchants and Manufacturers". Philadelphia. 1886. p. 167.

- Hanks 1982, p. 38.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996.

- Daniel Pabst Cabinet Maker business card, from Bryn Mawr College.

- Antique Gothic Style Pabst Oak Bench Pew, from Live Auctioneers.

- Victorian Modern Gothic hall bench, from Live Auctioneers.

- Hanks & Talbott 1977, p. 9.

- Burke 1986, p. 461.

- Hanks 1982, p. 36.

- Hanks & Talbott 1977, p. 7, citing The Evening Bulletin, June 11, 1910.

- Hanks 1982, p. 43.

- Honor Men Awards, from University of Pennsylvania.

- Helena Pabst, from Find-A-Grave.

- Hanks & Talbott 1977, pp. 3-5.

- Hanks & Talbott 1977, pp. 11, 15.

- Cooper 2007, p. 54.

- Cooper 2007, quoted throughout article.

- Renaissance Revival sideboard, from Antiques & Fine Art (Summer 2014).

- Hanks & Peirce 1983, p. 34.

- Neo-Grec music cabinet, from Live Auctioneers.

- McKean sideboard Archived 2014-12-19 at the Wayback Machine, from J&L Antiques.

- Renaissance Revival sideboard Archived 2014-12-27 at the Wayback Machine, from Biggs Museum of American Art.

- Ebonized pedestal, from Cleveland Museum of Art.

- Fox and Crane sideboard, from Art Institute of Chicago.

- PAFA armchair, from Victoria and Albert Museum.

- PAFA armchair at Allentown Art Museum, from Flickr.

- Roosevelt dining table Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, from High Museum of Art.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 175, 182–83.

- Modern Gothic pedestal, from Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Modern Gothic exhibition cabinet, from Brooklyn Museum.

- Modern Gothic exhibition cabinet, from Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute.

- Modern Gothic smokers cabinet, from iCollector.

- Ebonized fire screen, from Christie's New York.

- Glenview entrance hall, from Beau Stanton.

- Hanks & Talbott 1977, p. 22.

- Glenview staircase, from Hudson River Museum.

- Glenview library, from Flickr.

- Glenview sitting room, from Mattie's Blog.

- Glenview parlor, c. 1886, from Wikimedia Commons.

- Glenview sideboard (far right), from Mattie's Blog.

- Social Arts Club, from frankfurness.org.

- Iams 1993.

- Rittenhouse Club mantel, from Live Auctioneers.

- Thomas & Doebley 1976, pp. 116–17.

- Thomas, Cohen & Lewis 1996, pp. 209–10.

- Emlen Physick Estate, from Cape May Times (no date).

- Dr. Emlen Physick's bedroom. Archived 2014-12-31 at the Wayback Machine from Cape May MAC.

- Mrs. Ralston's bed, from Garden State Legacy.

- Pair of Modern Gothic pedestals, from Live Auctioneers.

- Ebonized chair, from Brooklyn Museum.

- Jean Zimmerman, "Magnificent Obsession," The New York Times Magazine, November 4, 2012.

- Hanks & Talbott 1977, p. 23.

- Hanging cabinet, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Renaissance Revival exhibition cabinet, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Parry mirror, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Lea music cabinet, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Pier mirror, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Modern Gothic desk, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Modern Gothic chair, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Neo-Grec partners desk, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Hanks & Talbott 1977, cover, pp. 16-18.

- Modern Gothic tall case clock, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- Pabst-Furness bookcase Archived 2014-12-24 at the Wayback Machine, from University of Pennsylvania.

- Henry Charles Lea Library, from University of Pennsylvania.

- Peters 2000, pp. 49–50.

- Sewell 1976, p. 403.

- Daniel Pabst Vanity (thumbnail), from S & S Auctions.

- Cooper 2007, illustration, p. 61.

Sources

- "Decorative Fine-Art Work at Philadelphia : American Furniture". American Architect and Building News. James R. Osgood & Company. 2. January 6, 1877.

- Ames, Kenneth (1 January 1970). Renaissance Revival Furniture in America. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burke, Doreen Bolger, ed. (1986). In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement. Metropolitan Museum of Art. cover, pp. 142, 146-47, 460-61. ISBN 978-0-87099-468-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooper, Dan (Fall 2007). "Daniel Pabst, Modern Gothic Furniture". Style 1900 Magazine: 54–61.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eastlake, Charles Locke (1872). Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery, and Other Details. (1st American ed.) Charles C. Perkins.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Robert (November 2008). "Iz You Iz or Iz You Ain't Daniel Pabst : PMA Tries to Find Out". Archived from the original on 2009-01-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanks, David (1982). "Daniel Pabst". Nineteenth Century Furniture : Innovation, Revival, and Reform. New York, N.Y: Art & Antiques. cover, pp. 36-43. ISBN 0-8230-8004-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanks, David (1983). The Quest for Unity : American Art between World's Fairs, 1876–1893. Detroit Institute of Arts. ISBN 978-0-89558-098-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanks, David A.; Peirce, Donald C. (1983). The Virginia Crawford Carroll Collection: American Decorative Arts, 1825–1917. Atlanta, Georgia: High Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-93980-216-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanks, David A.; Talbott, Page (April 1977). "Daniel Pabst: Philadelphia Cabinetmaker". Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin. 73 (316): 5. doi:10.2307/3795335. ISSN 0031-7314. JSTOR 3795335.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Iams, David (2 May 1993). "The Exclusive-club Life In Philadelphia Is Taking A Clubbing / Of The Most Prestigious Gathering Places, The Rittenhouse May Have Suffered The Most Of Late". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 25 December 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Iams, David (6 April 2002). "Furness library interior for sale". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 25 December 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaplan, Wendy (May 1987). "The Furniture of Frank Furness". The Magazine Antiques. 131 (5): 1088–95.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaplan, Wendy (1987). The Art That Is Life: The Arts & Crafts Movement in America, 1875–1920. Little Brown and Company; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. ISBN 0-87846-278-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Michael J. (2001). Frank Furness : Architecture and the Violent Mind. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-3937-3063-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madigan, Mary Jean (1973). Eastlake-Influenced American Furniture, 1870–1890: Catalogue of an Exhibition November 18, 1973-January 6, 1974. Hudson River Museum. cover, plates 10-12. ISBN 978-0-87100-043-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Panetta, Roger G. (2006). Westchester : The American Suburb. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-2594-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peters, Edward (2000). "Henry Charles Lea and the Libraries within the Library (PDF)" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Library.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sewell, Darrel, ed. (1976). Philadelphia, Three Centuries of American Art: Bicentennial exhibition, April 11-October 10, 1976 [catalogue]. Philadelphia Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87633-016-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Solis-Cohen, Lita (5 March 2014). "Winterthur's Philadelphia Furniture Forum: What Was Learned?". Furniture News. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sullivan, Louis H. (1924). The Autobiography of an Idea. Dover, 1956 reprint.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, George E.; Brownlee, David B. (2000). Building America's First University: An Historical and Architectural Guide to the University of Pennsylvania. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3515-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, George E.; Cohen, Jeffrey A.; Lewis, Michael J. (1996). Frank Furness : The Complete Works (2nd ed.). Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 1-56898-094-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, George E.; Doebley, Carl (1976). Cape May : Queen of the Seaside Resorts. The Art Alliance Press. ISBN 978-0-8798-2016-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson Brothers & Co. (1885). Catalogue of Work Executed. Philadelphia: Lippincott. p. 4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zwilling, Jennifer A. (Summer 2012). "Period Room Architecture in American Art Museums : Interior Woodwork from 1921 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Built 1871, Renovated Pre-1885". Winterthur Portfolio. 46 (2/3): 44–57. doi:10.1086/668451. ISSN 0084-0416. JSTOR 3739864.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Daniel Pabst. |

- Daniel Pabst at Find a Grave

- "Cabinet, attributed to Daniel Pabst". The Collection Online. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2014. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- "Daniel Pabst Cabinet Maker" business card, from Bryn Mawr College.

- Daniel Pabst from Live Auctioneers

- Daniel Pabst from Furnesque on Tumblr

- Daniel Pabst on Pinterest