Dacre Castle

Dacre Castle is a moated tower house in the village of Dacre, 4 miles (6.4 km) south-west of Penrith, Cumbria. It was constructed in the mid-14th century, probably by Margaret Multon, against the background of the threat of Scottish invasion and raids, and was held in the Dacre family until the 17th century. The tower house is 66 feet (20 m) tall, built out of local sandstone, topped by crenellations, with four turrets protruding from a central block, and includes an ornate lavabo in the main hall. Renovated during the 1670s and 1960s after periods of disrepair, the castle is now used as a private home.

| Dacre Castle | |

|---|---|

| Dacre, England | |

.jpg) The tower house of Dacre Castle | |

Dacre Castle | |

| Coordinates | 54.6316°N 2.8365°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference NY461266 |

| Type | Tower house and moated enclosure |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Privately occupied |

| Open to the public | No |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Sandstone |

History

Dacre Castle was probably built by Margaret Multon, the wife of Ralph Dacre, in the middle of the 14th century.[1] The Dacre family had risen in prominence in Cumbria during the 12th and early 13th centuries, and William Dacre, Ralph's father, had acquired a licence to crenellate the property of Dunmallogt in 1307, quite close to the future site of Dacre Castle.[2] Ralph married Margaret in 1317, becoming extremely wealth as a result, and received permission to found Naworth Castle in 1335.[2] Margaret built Dacre Castle at some point between Ralph's death in 1339 and 1354, with the intention of creating a fortified home.[1] Many tower houses were built across the region during the period in response to the threat of Scottish raids and invasions.[3] There may have been an older building already on the site, possibly moated, but this is uncertain.[2]

After Margaret's death, the castle continued to be owned by the Dacre family until the death of Randal Dacre in 1634, when it passed briefly to the Crown.[4] By 1675 the castle had become derelict and was restored by the then Lord Dacre, Thomas Lennard.[5] A new entrance to the castle was constructed and square, 17th-century windows installed.[6] After Thomas's death in 1715 the castle was sold to Edward Hassell.[7] The condition of the castle deteriorated again in the 18th century, becoming overgrown and dilapidated, and by the 19th century the Hassell family were using it as a farmhouse.[8]

In 1961, the castle was leased for 22 years by Anthony and Bunty Kinsman, at a cost of £1,000.[9] The property required extensive structural repairs and renovations in order to be made habitable, which the Kinsmans undertook over the next two years. The construction work cost £8,596, and some financial support was provided by the Ministry of Works in exchange for the castle being opened to the public for the next fifteen years.[10] The new oak doors in the castle were fitted with iron hinges that had originally been used in nearby Lowther Castle.[11] In 1967, the castle was visited by Princess Sharada Shah, the daughter of the King Mahendra of Nepal, as part of an official trip to the UK.[12]

In the 21st century the castle is owned by the Hassell-McCosh family and is rented out as a private home.[13] It is protected under UK law as a grade I listed building.[14]

Architecture

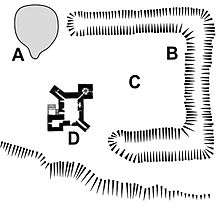

Dacre Castle lies in a valley, overlooking a stream and fields.[15] It comprises a tower house surrounded by a three-sided moat, creating an enclosed courtyard to the east 73 metres (240 ft) by 55 metres (180 ft) across.[15] The moat is between 9 metres (30 ft) to 15 metres (49 ft) wide and up to 4.5 metres (15 ft) deep, with a protective bank on the south and west sides; originally a wall would have surrounded the outside of the courtyard.[16] The courtyard originally held various buildings, possibly stables and offices, but the tower house was designed to operate independently, without the need for attached facilities.[17] Architecturally, the design of Dacre resembles Harewood and Langley Castles.[2]

The tower house is in the north-east corner of the enclosure and takes the form of a square, central block, with two large turrets on one side and two smaller turrets resembling angular buttresses on the other.[18] It is made of large blocks of local sandstone and the roof is crenellated.[19] The central block is 36 feet (11 m) by 20 feet (6.1 m) inside, and is 66 feet (20 m) tall, with 8.5 feet (2.6 m) thick walls.[18] The building was originally entered through the south-west turret on the ground-floor, but since the 17th century the entrance way has been directly into the central block up an exterior staircase.[2]

The ground floor of the central block contains two vaulted chambers and the first-floor forms a hall containing an ornate lavabo, with smaller chambers in the turrets.[20] The second floor similarly forms a single large chamber, 17 feet (5.2 m) high, with rooms in each of the adjacent turrets, and is traditionally called the "Room of the Three Kings", after the legend described by William of Malmesbury.[18][nb 1] In the 14th century, these large chambers would have been subdivided into smaller rooms.[4] The renovations in the 1960s uncovered a possible priest hole behind the fireplace in the Room of the Three Kings, 7 feet (2.1 m) by 4 feet (1.2 m); this chamber was re-sealed to avoid the cost of restoring it.[22]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dacre Castle. |

Notes

- The link between Dacre Castle and the "three kings" comes from William of Malmesbury's 12th-century account of Constantine III of Scotland, Owain ap Dyfnwal of the Cumbrians and King Æthelstan of England meeting at Dacre in the year 927.[21]

References

- Emery 1996, pp. 204–205

- Emery 1996, p. 204

- Pounds 1994, pp. 286–287

- Emery 1996, p. 205

- Mackenzie 1896, p. 309; Emery 1996, p. 204; Pettifer 2002, p. 40

- Mackenzie 1896, p. 309; Emery 1996, p. 204

- Lysons & Lysons 1816, p. 89; Murray 1869, p. 83

- Lysons & Lysons 1816, p. 89; Murray 1869, p. 83; "List Entry Summary: Moated Site of Dacre Castle", English Heritage, archived from the original on 29 October 2013, retrieved 12 October 2013

- Kinsman 1971, pp. 3, 10

- Kinsman 1971, pp. 4–7, 10, 17, 64

- Kinsman 1971, p. 19

- Kinsman 1971, p. 115

- "Ghost of Chance to See Something Special During Castle Open Days", Cumberland and Westmoreland Herald, 1 May 2009, retrieved 12 October 2013

- "List Entry Summary: Moated Site of Dacre Castle", English Heritage, archived from the original on 29 October 2013, retrieved 12 October 2013

- Emery 1996, p. 204; Pettifer 2002, p. 40

- Emery 1996, p. 204; "List Entry Summary: Moated Site of Dacre Castle", English Heritage, archived from the original on 29 October 2013, retrieved 12 October 2013

- Emery 1996, p. 204; Mackenzie 1896, p. 310; Pounds 1994, p. 287

- Emery 1996, p. 204; Mackenzie 1896, p. 310

- Emery 1996, p. 205; "List Entry Summary: Moated Site of Dacre Castle", English Heritage, archived from the original on 29 October 2013, retrieved 12 October 2013

- Kinsman 1971, p. 18; Emery 1996, p. 204

- Mackenzie 1896, p. 308

- Kinsman 1971, p. 18

Bibliography

- Emery, Anthony (1996). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500. 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49723-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kinsman, Bunty (1971). Pawn Takes Castle. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Oriel Press. ISBN 978-0-85362-132-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lysons, Daniel; Lysons, Samuel (1816). Magna Britannia: Being a Concise Topographical Account of the Several Counties of Great Britain. 4. London, UK: Cadell and Davies. OCLC 257401015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896). The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure. 2. New York, US: Macmillan. OCLC 504892038.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murray, John (1869). Handbook for Westmorland, Cumberland and the Lakes (2nd ed.). London, UK: John Murray. OCLC 5358890.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pettifer, Adrian (2002). English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pounds, N. J. G. (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45099-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Stretton, E. H. A. (1994). Dacre Castle. Penrith, UK: Hayloft Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9518690-1-7.