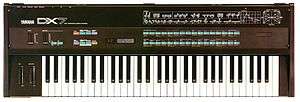

Yamaha DX7

The Yamaha DX7 is a synthesizer manufactured by the Yamaha Corporation from 1983 to 1989. It was the first successful digital synthesizer and is one of the bestselling synthesizers in history, selling over 200,000 units.

| Yamaha DX7 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Manufacturer | Yamaha |

| Dates | 1983–1989 |

| Price | $1,995 US £1,495 GBP ¥248,000 JPY |

| Technical specifications | |

| Polyphony | 16-voice |

| Timbrality | Monotimbral Bi-timbral (DX7 II) |

| Oscillator | 6 digital sine wave operators per voice, 32 patching algorithms[1] |

| Synthesis type | Digital linear frequency modulation / Additive synthesis (alg. #32) |

| Filter | none |

| Attenuator | 1 pitch envelope & 6 amplitude generators per voice |

| Aftertouch expression | Yes (channel) |

| Velocity expression | Yes |

| Storage memory | 32 patches in RAM (battery backup); front panel ROM/RAM cartridge port |

| Effects | none |

| Hardware | YM21280 (OPS) operator chip YM21290 (EGS) envelope generator |

| Input/output | |

| Keyboard | 61-note with velocity and aftertouch sensitivity |

| Left-hand control | pitch-bend and modulation wheels |

| External control | MIDI in/out/thru, input for foot controller x2, input for foot switch x2, input for optional breath controller |

In the early 1980s, the synthesizer market was dominated by analog synthesizers. FM synthesis, a means of generating sounds via frequency modulation, was developed by John Chowning at Stanford University, California. FM synthesis created brighter, "glassier" sounds, and could better imitate acoustic sounds such as brass. Yamaha licensed the technology to create the DX7, combining it with very-large-scale integration chips to lower manufacturing costs.

With its complex menus and lack of conventional controls, few learned to program the DX7 in depth. However, its preset sounds became staples of 1980s pop music, used by artists including A-ha, Kenny Loggins, Kool & the Gang, Whitney Houston, Chicago, Phil Collins, Luther Vandross, and Billy Ocean. Its electric piano sound was particularly widely used, especially in power ballads. Producer Brian Eno mastered the programming and it was instrumental to his work in ambient music.

The DX7 was succeeded by FM synthesizers including the DX1, DX5, DX9, DX11, DX21, DX27 and DX100.

Development

By the mid-20th century, frequency modulation (FM), a means of carrying sound, had been understood for decades and was widely used to broadcast radio transmissions.[2] In the 1960s, at Stanford University, California, John Chowning developed FM synthesis, a means of using FM to generate sounds different from analog synthesis. In 1971, to demonstrate its commercial potential, Chowning used FM to emulate acoustic sounds such as organs and brass. Stanford patented the technology and hoped to license it, but was turned down by American companies including Hammond and Wurlitzer.[3] Chowning felt their engineers, who were used to analog synthesis, did not understand FM.[4]

At the time, the Japanese company Yamaha was the world's largest manufacturer of musical instruments but had little market share in the United States.[4] One of their chief engineers visited Stanford and, according to Chowning, "in ten minutes he understood ... I guess Yamaha had already been working in the digital domain, so he knew exactly what I was saying."[4] Yamaha licensed the technology for one year to determine its commercial viability, and in 1973 its organ division began developing a prototype FM monophonic synthesizer. In 1975, Yamaha negotiated exclusive rights for the technology.[3] Roland founder Ikutaro Kakehashi was also interested, but met Chowning six months after Yamaha had agreed the deal; Kakehashi later said Yamaha were the natural partners in the venture, as they had the resources to make FM synthesis commercially viable.[2]

Yamaha created the first hardware implementation of FM synthesis.[4] The first commercial FM synthesizer was the Yamaha GS1, released in 1980,[5] which was expensive to manufacture due to its integrated circuit chips.[4] At the same time, Yamaha was developing the means to manufacture very-large-scale integration chips; these allowed the DX7 to use only two chips, compared to the GS1's 50.[4] Yamaha also altered the implementation of the FM algorithms in the DX7 to gain efficiency and speed, producing a sampling rate higher than the digital synthesizers at Stanford. According to Chowning, "The consequence is that the bandwidth of the DX7 gives a really brilliant kind of sound ... I think it's quite noticeable."[4]

Yamaha displayed a prototype of the DX7 in 1982, branded the CSDX, in reference to the Yamaha CS range of analog synthesizers.[6] In late 1982, Briton Dave Bristow and American Gary Leuenberger, experts on the Yamaha CS-80 synthesizer, were flown to Japan to develop the DX7's voices. They had less than four days to create the DX7's 128 preset patches.[7]

Features

Compared to the "warm" and "fuzzy" sounds of analog synthesizers, the digital DX7 sounds "harsh", "glassy" and "chilly",[8] with a richer, brighter sound.[9] Its preset sounds constitute "struck" and "plucked" sounds with complex transients.[9] Its keyboard spans five octaves,[7] with sixteen-note polyphony, meaning sixteen notes can sound simultaneously. It has 32 algorithms, each a different arrangement of its six sine wave operators.[9] The keyboard expression allows for velocity sensitivity and aftertouch.[7] It was the first synthesizer with a liquid-crystal display, and the first to allow users to name patches.[7]

Sales

The DX7 was the first commercially successful digital synthesizer[10][11][12] and remains one of the bestselling synthesizers in history.[11][13] According to Bristow, Yamaha had hoped the DX7 would sell more than 20,000 units; within a year, orders exceeded 150,000,[7] and it had sold 200,000 units after three years.[14] It was the first synthesizer to sell more than 100,000 units.[7] Yamaha manufactured units on a scale American competitors could not match; by comparison, Moog sold 12,000 Minimoog synthesizers in 11 years, and could not meet demand.[14] The FM patent was for years one of Stanford's highest earning.[15] Chowning received royalties for all of Yamaha's FM synthesizers.[3]

According to Dave Smith, founder of the synthesizer company Sequential, "The synthesizer market was tiny in the late seventies. No one was selling 50,000 of these things. It wasn't until the Yamaha DX7 came out that a company shipped 100,000-plus synths."[16] Smith said the DX7 sold well as it was reasonably priced, had keyboard expression and 16 voices, and importantly was better at emulating acoustic sounds than its rivals.[16] Chowning credited the success to the combination of his FM patent with Yamaha's chip technology.[4]

Impact

At the time of release, the DX7 was the first digital synthesizer most musicians had used.[8] It was very different from the analog synthesizers that had dominated the market; according to MusicRadar, its "spiky" and "crystalline" sounds made it "the perfect antidote to a decade of analog waveforms".[17]

With complex submenus displayed on an LCD and no knobs and sliders to adjust the sound, many found the DX7 difficult to program.[18] MusicRadar described its interface as "nearly impenetrable architecture consisting of operators, algorithms and unusual envelopes, all accessed through tedious menus and a diminutive display".[17] Rather than create their own sounds, most users used the presets,[8] which became widely used in 1980s pop music.[9] The "BASS 1" preset was used on songs such as "Take On Me" by A-ha, "Danger Zone" by Kenny Loggins, and "Fresh" by Kool & the Gang.[8] The "E PIANO 1" preset became particularly famous,[8][19] especially for power ballads,[20] and was used by artists including Whitney Houston, Chicago,[20] Prince[9] Phil Collins, Luther Vandross, Billy Ocean,[8] and Celine Dion.[21] Another popular preset imitates the sound of a Rhodes piano, and prompted several players to abandon the Rhodes in favor of the DX7.[22]

A few musicians skilled at programming the DX7 found employment creating sounds for other acts.[23] Brian Eno learned to program the DX7 in depth and used it to create ambient music on his 1983 album Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks.[8] He shared instructions for recreating his patches in a 1987 issue of Keyboard magazine.[18] As a producer, Eno used the DX7 on records by U2 and Coldplay.[8] In later years, the DX sounds came to be seen as dated or cliched, and interest in FM synthesis declined, with used digital synthesizers selling for less than analog.[8]

Successors

According to Sound on Sound, throughout the mid-1980s, "Yamaha flooded the market with a plethora of low-cost FM synths."[6] In 1987, it released the DX7II, though it did not match its predecessor's success.[7] Further successors included the TX81Z, DX1, DX11, and DX21.[6] Yamaha manufactured reduced versions of the DX sound chip, such as the YM2612, for use in technologies such as the Sega Genesis game console.[24] In 2015, Yamaha released an updated, smaller FM synthesizer, the Reface DX.[25]

See also

- Yamaha DX1

- DX11

- DX21

- DX27

- DX100

References

-

"Chapter 2: FM Tone Generators and the Dawn of Home Music Production". History, Yamaha Synth 40th Anniversary. Yamaha Corporation. 2014.

At that time, a number of Yamaha departments were developing different instruments in parallel, ... the direct forerunner of the DX Series synths was a test model known as the Programmable Algorithm Music Synthesizer (PAMS). In recognition of this fact, the DX7 is identified as a Digital Programmable Algorithm Synthesizer on its top panel. / As its name suggests, the PAMS created sound based on various calculation algorithms—namely, phase modulation, amplitude modulation, additive synthesis, and frequency modulation (FM)—and from the very start, the prototype supported the storing of programs in memory. However, this high level of freedom in sound design came at the price of a huge increase in the number of parameters required, meaning that the PAMS was not yet suitable for commercialization as an instrument that the average user could program. / In order to resolve this issue, the Yamaha developers decided to simplify the synth's tone generator design by having the modulator and carrier envelope generators share common parameters. They also reduced the number of algorithms—or operator combination patterns—to 32.

- "The History Of Roland: Part 2". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- "John Chowning |". www.soundonsound.com. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Darter, Tom. "John Chowning" (PDF). Stanford University.

- Curtis Roads (1996). The computer music tutorial. MIT Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-262-68082-3. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- Gordon Reid (September 2001). "Sounds of the '80s Part 2: The Yamaha DX1 & Its Successors (Retro)". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- Vail, Mark (2014). The Synthesizer. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0195394895.

- "The 14 most important synths in electronic music history – and the musicians who use them". FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music. 2016-09-15. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Brøvig-Hanssen, Ragnhild; Danielsen, Anne (2016-02-19). Digital Signatures: The Impact of Digitization on Popular Music Sound. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262034142.

-

Edmondson, Jacqueline, ed. (2013). Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars, and Stories that Shaped our Culture [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 398. ISBN 9780313393488.

In 1967, John Chowning, at Stanford University, accidentally discovered frequency modulation (FM) synthesis when experimenting with extreme vibrato effects in MUSIC-V. ... By 1971 he was able to use FM synthesis to synthesizer musical instrument sounds, and this technique was later used to create the Yamaha DX synthesizer, the first commercially successful digital synthesizer, in the early 1980s.

-

Shepard, Brian K. (2013). Refining Sound: A Practical Guide to Synthesis and Synthesizers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199376681.

The first digital synthesizer to make it into the studios of everyone else, the Yamaha DX7, became one of the most commercially successful synthesizers of all time.

-

Pinch, T. J.; Bijsterveld, Karin (July 2003). ""Should One Applaud?" Breaches and Boundaries in the Reception of New Technology in Music". Technology and Culture. 44 (3): 536–559. doi:10.1353/tech.2003.0126.

By the time the first commercially successful digital instrument, the Yamaha DX7 (lifetime sales of two hundred thousand), appeared in 1983 ...

(Note: the above sales number seems about whole DX series) - Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Computer Music". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 257. ISBN 0415957818. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- "Red Bull Music Academy Daily". daily.redbullmusicacademy.com. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Pinch, Trevor; Trocco, Frank (2004). Analog Days. Harvard University Press.

- "Dave Smith". KeyboardMag. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- "The top 10 classic synth presets (and where you can hear them)". MusicRadar. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- "Sound like Brian Eno with his Yamaha DX7 synth patches from 1987". FACT Magazine: Music News, New Music. 2017-05-12. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- "The top 10 classic synth presets (and where you can hear them)". MusicRadar. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Simpson, Dave (2018-08-14). "More synthetic bamboo! The greatest preset sounds in pop music". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Saxelby, Ruth. "Borne into the 90s [pt.1]". Dummy Mag. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- Verderosa, Tony (2002). The Techno Primer: The Essential Reference for Loop-based Music Styles. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-634-01788-9.

- Roger T. Dean, ed. (September 16, 2009). The Oxford Handbook of Computer Music. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780199887132.

- Stuart, Keith (2020-02-13). "Super Sonic: creating the new sound of Sega's hedgehog hit". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- Goldman 2015-10-13T19:59:00.285Z, Dan 'JD73'. "Yamaha Reface DX review". MusicRadar. Retrieved 2020-02-02.