DPPH

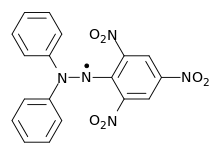

DPPH is a common abbreviation for the organic chemical compound 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl. It is a dark-colored crystalline powder composed of stable free-radical molecules. DPPH has two major applications, both in laboratory research: one is a monitor of chemical reactions involving radicals, most notably it is a common antioxidant assay,[1] and another is a standard of the position and intensity of electron paramagnetic resonance signals.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

di(phenyl)-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)iminoazanium | |

| Other names

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl)hydrazyl Diphenylpicrylhydrazyl | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| Abbreviations | DPPH |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.993 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C18H12N5O6 | |

| Molar mass | 394.32 g/mol |

| Appearance | Black to green powder, purple in solution |

| Density | 1.4 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 135 °C (275 °F; 408 K) (decomposes) |

| insoluble | |

| Solubility in methanol | 10 mg/mL |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | MSDS |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Properties and applications

DPPH has several crystalline forms which differ by the lattice symmetry and melting point (m.p.). The commercial powder is a mixture of phases which melts at ~130 °C. DPPH-I (m.p. 106 °C) is orthorhombic, DPPH-II (m.p. 137 °C) is amorphous and DPPH-III (m.p. 128–129 °C) is triclinic.[2]

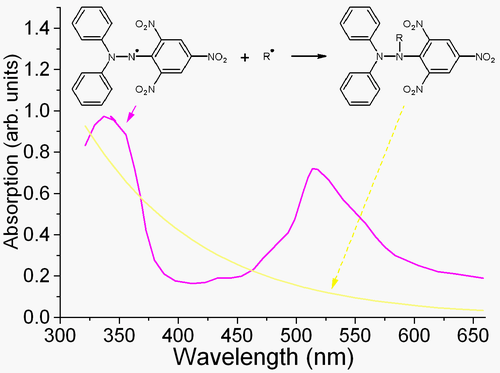

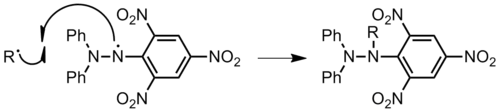

DPPH is a well-known radical and a trap ("scavenger") for other radicals. Therefore, rate reduction of a chemical reaction upon addition of DPPH is used as an indicator of the radical nature of that reaction. Because of a strong absorption band centered at about 520 nm, the DPPH radical has a deep violet color in solution, and it becomes colorless or pale yellow when neutralized. This property allows visual monitoring of the reaction, and the number of initial radicals can be counted from the change in the optical absorption at 520 nm or in the EPR signal of the DPPH.[3]

Because DPPH is an efficient radical trap, it is also a strong inhibitor of radical-mediated polymerization.[4]

As a stable and well-characterized solid radical source, DPPH is the traditional and perhaps the most popular standard of the position (g-marker) and intensity of electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signals – the number of radicals for a freshly prepared sample can be determined by weighing and the EPR splitting factor for DPPH is calibrated at g = 2.0036. DPPH signal is convenient by that it is normally concentrated in a single line, whose intensity increases linearly with the square root of microwave power in the wider power range. The dilute nature of the DPPH radicals (one unpaired spin per 41 atoms) results in a relatively small linewidth (1.5–4.7 Gauss). The linewidth may however increase if solvent molecules remain in the crystal and if measurements are performed with a high-frequency EPR setup (~200 GHz), where the slight g-anisotropy of DPPH becomes detectable.[5][6]

Whereas DPPH is normally a paramagnetic solid, it transforms into an antiferromagnetic state upon cooling to very low temperatures of the order 0.3 K. This phenomenon was first reported by Alexander Prokhorov in 1963.[7][8][9][10]

References

- DPPH antioxidant assay revisited. Om P. Sharma and Tej K. Bhat, Food Chemistry, Volume 113, Issue 4, 15 April 2009, Pages 1202–1205, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.08.008

- Kiers, C. T.; De Boer, J. L.; Olthof, R.; Spek, A. L. (1976). "The crystal structure of a 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) modification". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 32 (8): 2297. doi:10.1107/S0567740876007632.

- Mark S. M. Alger (1997). Polymer science dictionary. Springer. p. 152. ISBN 0-412-60870-7.

- Cowie, J. M. G.; Arrighi, Valeria (2008). Polymers: Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials (3rd ed.). Scotland: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-9813-1.

- M.J. Davies (2000). Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 178. ISBN 0-85404-310-1.

- Charles P. Poole (1996). Electron spin resonance: a comprehensive treatise on experimental techniques. Courier Dover Publications. p. 443. ISBN 0-486-69444-5.

- A. M. Prokhorov and V.B. Fedorov, Soviet Phys. JETP 16 (1963) 1489.

- Teruaki Fujito (1981). "Magnetic Interaction in Solvent-free DPPH and DPPH–Solvent Complexes". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 54 (10): 3110. doi:10.1246/bcsj.54.3110.

- Stig Lundqvist (1998). "A. M. Prokhorov". Nobel lectures in physics, 1963-1970. World Scientific. p. 118. ISBN 981-02-3404-X.

- Aleksandr M. Prokhorov, The Nobel Prize in Physics 1964