Web Ontology Language

The Web Ontology Language (OWL) is a family of knowledge representation languages for authoring ontologies. Ontologies are a formal way to describe taxonomies and classification networks, essentially defining the structure of knowledge for various domains: the nouns representing classes of objects and the verbs representing relations between the objects. Ontologies resemble class hierarchies in object-oriented programming but there are several critical differences. Class hierarchies are meant to represent structures used in source code that evolve fairly slowly (typically monthly revisions) whereas ontologies are meant to represent information on the Internet and are expected to be evolving almost constantly. Similarly, ontologies are typically far more flexible as they are meant to represent information on the Internet coming from all sorts of heterogeneous data sources. Class hierarchies on the other hand are meant to be fairly static and rely on far less diverse and more structured sources of data such as corporate databases.[1]

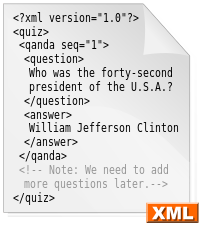

The OWL languages are characterized by formal semantics. They are built upon the World Wide Web Consortium's (W3C) XML standard for objects called the Resource Description Framework (RDF).[2] OWL and RDF have attracted significant academic, medical and commercial interest.

In October 2007,[3] a new W3C working group[4] was started to extend OWL with several new features as proposed in the OWL 1.1 member submission.[5] W3C announced the new version of OWL on 27 October 2009.[6] This new version, called OWL 2, soon found its way into semantic editors such as Protégé and semantic reasoners such as Pellet,[7] RacerPro,[8] FaCT++[9][10] and HermiT.[11]

The OWL family contains many species, serializations, syntaxes and specifications with similar names. OWL and OWL2 are used to refer to the 2004 and 2009 specifications, respectively. Full species names will be used, including specification version (for example, OWL2 EL). When referring more generally, OWL Family will be used.[12][13][14]

History

Early ontology languages

There is a long history of ontological development in philosophy and computer science. Since the 1990s, a number of research efforts have explored how the idea of knowledge representation (KR) from artificial intelligence (AI) could be made useful on the World Wide Web. These included languages based on HTML (called SHOE), based on XML (called XOL, later OIL), and various frame-based KR languages and knowledge acquisition approaches.

Ontology languages for the web

In 2000 in the United States, DARPA started development of DAML led by James Hendler.[15] In March 2001, the Joint EU/US Committee on Agent Markup Languages decided that DAML should be merged with OIL.[15] The EU/US ad hoc Joint Working Group on Agent Markup Languages was convened to develop DAML+OIL as a web ontology language. This group was jointly funded by the DARPA (under the DAML program) and the European Union's Information Society Technologies (IST) funding project. DAML+OIL was intended to be a thin layer above RDFS,[15] with formal semantics based on a description logic (DL).[16]

DAML+OIL is a particularly major influence on OWL; OWL's design was specifically based on DAML+OIL.[17]

Semantic web standards

The Semantic Web provides a common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise, and community boundaries.

— World Wide Web Consortium, W3C Semantic Web Activity[18]

RDF schema

a declarative representation language influenced by ideas from knowledge representation

— World Wide Web Consortium, Metadata Activity[19]

In the late 1990s, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Metadata Activity started work on RDF Schema (RDFS), a language for RDF vocabulary sharing. The RDF became a W3C Recommendation in February 1999, and RDFS a Candidate Recommendation in March 2000.[19] In February 2001, the Semantic Web Activity replaced the Metadata Activity.[19] In 2004 (as part of a wider revision of RDF) RDFS became a W3C Recommendation.[20] Though RDFS provides some support for ontology specification, the need for a more expressive ontology language had become clear.[21]

Web-Ontology Working Group

As of Monday, the 31st of May, our working group will officially come to an end. We have achieved all that we were chartered to do, and I believe our work is being quite well appreciated.

— James Hendler and Guus Schreiber, Web-Ontology Working Group: Conclusions and Future Work[22]

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) created the Web-Ontology Working Group as part of their Semantic Web Activity. It began work on November 1, 2001 with co-chairs James Hendler and Guus Schreiber.[22] The first working drafts of the abstract syntax, reference and synopsis were published in July 2002.[22] OWL became a formal W3C recommendation on February 10, 2004 and the working group was disbanded on May 31, 2004.[22]

OWL Working Group

In 2005, at the OWL Experiences And Directions Workshop a consensus formed that recent advances in description logic would allow a more expressive revision to satisfy user requirements more comprehensively whilst retaining good computational properties. In December 2006, the OWL1.1 Member Submission[23] was made to the W3C. The W3C chartered the OWL Working Group as part of the Semantic Web Activity in September 2007. In April 2008, this group decided to call this new language OWL2, indicating a substantial revision.[24]

OWL 2 became a W3C recommendation in October 2009. OWL 2 introduces profiles to improve scalability in typical applications.[6]

Acronym

Why not be inconsistent in at least one aspect of a language which is all about consistency?

— Guus Schreiber, Why OWL and not WOL?[25]

OWL was chosen as an easily pronounced acronym that would yield good logos, suggest wisdom, and honor William A. Martin's One World Language knowledge representation project from the 1970s.[26][27][28]

Adoption

A 2006 survey of ontologies available on the web collected 688 OWL ontologies. Of these, 199 were OWL Lite, 149 were OWL DL and 337 OWL Full (by syntax). They found that 19 ontologies had in excess of 2,000 classes, and that 6 had more than 10,000. The same survey collected 587 RDFS vocabularies.[29]

Ontologies

An ontology is an explicit specification of a conceptualization.

The data described by an ontology in the OWL family is interpreted as a set of "individuals" and a set of "property assertions" which relate these individuals to each other. An ontology consists of a set of axioms which place constraints on sets of individuals (called "classes") and the types of relationships permitted between them. These axioms provide semantics by allowing systems to infer additional information based on the data explicitly provided. A full introduction to the expressive power of the OWL is provided in the W3C's OWL Guide.[31]

OWL ontologies can import other ontologies, adding information from the imported ontology to the current ontology.[17]

Example

An ontology describing families might include axioms stating that a "hasMother" property is only present between two individuals when "hasParent" is also present, and that individuals of class "HasTypeOBlood" are never related via "hasParent" to members of the "HasTypeABBlood" class. If it is stated that the individual Harriet is related via "hasMother" to the individual Sue, and that Harriet is a member of the "HasTypeOBlood" class, then it can be inferred that Sue is not a member of "HasTypeABBlood". This is, however, only true if the concepts of "Parent" and "Mother" only mean biological parent or mother and not social parent or mother.

Species

OWL sublanguages

The W3C-endorsed OWL specification includes the definition of three variants of OWL, with different levels of expressiveness. These are OWL Lite, OWL DL and OWL Full (ordered by increasing expressiveness). Each of these sublanguages is a syntactic extension of its simpler predecessor. The following set of relations hold. Their inverses do not.

- Every legal OWL Lite ontology is a legal OWL DL ontology.

- Every legal OWL DL ontology is a legal OWL Full ontology.

- Every valid OWL Lite conclusion is a valid OWL DL conclusion.

- Every valid OWL DL conclusion is a valid OWL Full conclusion.

OWL Lite

OWL Lite was originally intended to support those users primarily needing a classification hierarchy and simple constraints. For example, while it supports cardinality constraints, it only permits cardinality values of 0 or 1. It was hoped that it would be simpler to provide tool support for OWL Lite than its more expressive relatives, allowing quick migration path for systems using thesauri and other taxonomies. In practice, however, most of the expressiveness constraints placed on OWL Lite amount to little more than syntactic inconveniences: most of the constructs available in OWL DL can be built using complex combinations of OWL Lite features, and is equally expressive as the description logic .[24] Development of OWL Lite tools has thus proven to be almost as difficult as development of tools for OWL DL, and OWL Lite is not widely used.[24]

OWL DL

OWL DL is designed to provide the maximum expressiveness possible while retaining computational completeness (either φ or ¬φ holds), decidability (there is an effective procedure to determine whether φ is derivable or not), and the availability of practical reasoning algorithms. OWL DL includes all OWL language constructs, but they can be used only under certain restrictions (for example, number restrictions may not be placed upon properties which are declared to be transitive; and while a class may be a subclass of many classes, a class cannot be an instance of another class). OWL DL is so named due to its correspondence with description logic, a field of research that has studied the logics that form the formal foundation of OWL.

OWL Full

OWL Full is based on a different semantics from OWL Lite or OWL DL, and was designed to preserve some compatibility with RDF Schema. For example, in OWL Full a class can be treated simultaneously as a collection of individuals and as an individual in its own right; this is not permitted in OWL DL. OWL Full allows an ontology to augment the meaning of the pre-defined (RDF or OWL) vocabulary. OWL Full is undecidable, so no reasoning software is able to perform complete reasoning for it.

OWL2 profiles

In OWL 2, there are three sublanguages of the language. OWL 2 EL is a fragment that has polynomial time reasoning complexity; OWL 2 QL is designed to enable easier access and query to data stored in databases; OWL 2 RL is a rule subset of OWL 2.

Syntax

The OWL family of languages supports a variety of syntaxes. It is useful to distinguish high level syntaxes aimed at specification from exchange syntaxes more suitable for general use.

High level

These are close to the ontology structure of languages in the OWL family.

OWL abstract syntax

High level syntax is used to specify the OWL ontology structure and semantics.[32]

The OWL abstract syntax presents an ontology as a sequence of annotations, axioms and facts. Annotations carry machine and human oriented meta-data. Information about the classes, properties and individuals that compose the ontology is contained in axioms and facts only. Each class, property and individual is either anonymous or identified by an URI reference. Facts state data either about an individual or about a pair of individual identifiers (that the objects identified are distinct or the same). Axioms specify the characteristics of classes and properties. This style is similar to frame languages, and quite dissimilar to well known syntaxes for DLs and Resource Description Framework (RDF).[32]

Sean Bechhofer, et al. argue that though this syntax is hard to parse, it is quite concrete. They conclude that the name abstract syntax may be somewhat misleading.[33]

OWL2 functional syntax

This syntax closely follows the structure of an OWL2 ontology. It is used by OWL2 to specify semantics, mappings to exchange syntaxes and profiles.[34]

Exchange syntaxes

| |

| Filename extension |

.owx, .owl, .rdf |

|---|---|

| Internet media type |

application/owl+xml, application/rdf+xml[35] |

| Developed by | World Wide Web Consortium |

| Standard | OWL 2 XML Serialization October 27, 2009, OWL Reference February 10, 2004 |

| Open format? | Yes |

RDF syntaxes

Syntactic mappings into RDF are specified[32][36] for languages in the OWL family. Several RDF serialization formats have been devised. Each leads to a syntax for languages in the OWL family through this mapping. RDF/XML is normative.[32][36]

OWL2 XML syntax

OWL2 specifies an XML serialization that closely models the structure of an OWL2 ontology.[37]

Manchester Syntax

The Manchester Syntax is a compact, human readable syntax with a style close to frame languages. Variations are available for OWL and OWL2. Not all OWL and OWL2 ontologies can be expressed in this syntax.[38]

Examples

- The W3C OWL 2 Web Ontology Language provides syntax examples.[39]

Tea ontology

Consider an ontology for tea based on a Tea class. First, an ontology identifier is needed. Every OWL ontology must be identified by a URI (http://www.example.org/tea.owl, say). This example provides a sense of the syntax. To save space below, preambles and prefix definitions have been skipped.

- OWL2 Functional Syntax

Ontology(<http://example.org/tea.owl> Declaration( Class( :Tea ) ) )

- OWL2 XML Syntax

<Ontology ontologyIRI="http://example.org/tea.owl" ...> <Prefix name="owl" IRI="http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#"/> <Declaration> <Class IRI="Tea"/> </Declaration> </Ontology>

- Manchester Syntax

Ontology: <http://example.org/tea.owl> Class: Tea

- RDF/XML syntax

<rdf:RDF ...> <owl:Ontology rdf:about=""/> <owl:Class rdf:about="#Tea"/> </rdf:RDF>

- RDF/Turtle

<http://example.org/tea.owl> rdf:type owl:Ontology . :Tea rdf:type owl:Class .

Semantics

Relation to description logics

OWL classes correspond to description logic (DL) concepts, OWL properties to DL roles, while individuals are called the same way in both the OWL and the DL terminology.[40]

In the beginning, IS-A was quite simple. Today, however, there are almost as many meanings for this inheritance link as there are knowledge-representation systems.

Early attempts to build large ontologies were plagued by a lack of clear definitions. Members of the OWL family have model theoretic formal semantics, and so have strong logical foundations.

Description logics are a family of logics that are decidable fragments of first-order logic with attractive and well-understood computational properties. OWL DL and OWL Lite semantics are based on DLs.[42] They combine a syntax for describing and exchanging ontologies, and formal semantics that gives them meaning. For example, OWL DL corresponds to the description logic, while OWL 2 corresponds to the logic.[43] Sound, complete, terminating reasoners (i.e. systems which are guaranteed to derive every consequence of the knowledge in an ontology) exist for these DLs.

Relation to RDFS

OWL Full is intended to be compatible with RDF Schema (RDFS), and to be capable of augmenting the meanings of existing Resource Description Framework (RDF) vocabulary.[44] A model theory describes the formal semantics for RDF.[45] This interpretation provides the meaning of RDF and RDFS vocabulary. So, the meaning of OWL Full ontologies are defined by extension of the RDFS meaning, and OWL Full is a semantic extension of RDF.[46]

Open world assumption

[The closed] world assumption implies that everything we don’t know is false, while the open world assumption states that everything we don’t know is undefined.

— Stefano Mazzocchi, Closed World vs. Open World: the First Semantic Web Battle[47]

The languages in the OWL family use the open world assumption. Under the open world assumption, if a statement cannot be proven to be true with current knowledge, we cannot draw the conclusion that the statement is false.

Contrast to other languages

A relational database consists of sets of tuples with the same attributes. SQL is a query and management language for relational databases. Prolog is a logical programming language. Both use the closed world assumption.

Terminology

Languages in the OWL family are capable of creating classes, properties, defining instances and its operations.

Instances

An instance is an object. It corresponds to a description logic individual.

Classes

A class is a collection of objects. A class may contain individuals, instances of the class. A class may have any number of instances. An instance may belong to none, one or more classes.

A class may be a subclass of another, inheriting characteristics from its parent superclass. This corresponds to logical subsumption and DL concept inclusion notated .

All classes are subclasses of owl:Thing (DL top notated ), the root class.

All classes are subclassed by owl:Nothing (DL bottom notated ), the empty class. No instances are members of owl:Nothing. Modelers use owl:Thing and owl:Nothing to assert facts about all or no instances.[48]

Class and their members can be defined in OWL either by extension or by intension. An individual can be explicitly assigned a class by a Class assertion, for example we can add a statement Queen elizabeth is a(n instance of) human, or by a class expression with ClassExpression statements every instance of the human class who has a female value to the sex property is an instance of the woman class.

Example

Let's call human the class of all humans in the world is a subclass of owl:thing. The class of all women (say woman) in the world is a subclass of human. Then we have

The membership of some individual to a class could be noted

ClassAssertion( human George_Washington )

and class inclusion

SubClassOf( woman human )

The first means "George Washington is a human" and the second "every woman is human".

Properties

A property is a characteristic of a class - a directed binary relation that specifies some attribute which is true for instances of that class. Properties sometimes act as data values, or links to other instances. Properties may exhibit logical features, for example, by being transitive, symmetric, inverse and functional. Properties may also have domains and ranges.

Datatype properties

Datatype properties are relations between instances of classes and RDF literals or XML schema datatypes. For example, modelName (String datatype) is the property of Manufacturer class. They are formulated using owl:DatatypeProperty type.

Object properties

Object properties are relations between instances of two classes. For example, ownedBy may be an object type property of the Vehicle class and may have a range which is the class Person. They are formulated using owl:ObjectProperty.

Operators

Languages in the OWL family support various operations on classes such as union, intersection and complement. They also allow class enumeration, cardinality, disjointness, and equivalence.

Metaclasses

Metaclasses are classes of classes. They are allowed in OWL full or with a feature called class/instance punning.

Public ontologies

Libraries

Biomedical

- OBO Foundry[49][50]

- NCBO BioPortal[51]

- NCI Enterprise Vocabulary Services

Standards

- Suggested Upper Merged Ontology[52]

- TDWG[53]

- PROV-O,[54] the ontology version of the W3C's PROV-DM[55]

- Basic Formal Ontology

- European Materials Modelling Ontology EMMO

Search

Limitations

- No direct language support for n-ary relationships. For example, modelers may wish to describe the qualities of a relation, to relate more than 2 individuals or to relate an individual to a list. This cannot be done within OWL. They may need to adopt a pattern instead which encodes the meaning outside the formal semantics.[57]

See also

- RDF

- Semantic technology

- Agris: International Information System for the Agricultural Sciences and Technology

- Common Logic

- FOAF + DOAC

- Frame language

- Geopolitical ontology

- IDEAS Group

- Meta-Object Facility (MOF), a different standard for the Unified Modeling Language (UML) of the Object Management Group (OMG)

- Metaclass (Semantic Web), a featured allowed by OWL to represent knowledge

- Multimedia Web Ontology Language

- Semantic reasoner

- SKOS

- SSWAP: Simple Semantic Web Architecture and Protocol

References

- Knublauch, Holger; Oberle, Daniel; Tetlow, Phil; Wallace, Evan (March 9, 2006). "A Semantic Web Primer for Object-Oriented Software Developers". W3C. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- "OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Document Overview (Second Edition)". W3C. 11 December 2012.

- "XML and Semantic Web W3C Standards Timeline" (PDF).

- "OWL". W3.org. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- "Submission Request to W3C: OWL 1.1 Web Ontology Language". W3C. 2006-12-19.

- "W3C Standard Facilitates Data Management and Integration". W3.org. 2009-10-27. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Sirin, E.; Parsia, B.; Grau, B. C.; Kalyanpur, A.; Katz, Y. (2007). "Pellet: A practical OWL-DL reasoner" (PDF). Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web. 5 (2): 51–53. doi:10.1016/j.websem.2007.03.004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-27.

- "RACER - Home". Racer-systems.com. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- Tsarkov, D.; Horrocks, I. (2006). "FaCT++ Description Logic Reasoner: System Description" (PDF). Automated Reasoning. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 4130. pp. 292–297. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.65.2672. doi:10.1007/11814771_26. ISBN 978-3-540-37187-8.

- "Google Code Archive - Long-term storage for Google Code Project Hosting". Code.google.com. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- "Home". HermiT Reasoner. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- Berners-Lee, Tim; James Hendler; Ora Lassila (May 17, 2001). "The Semantic Web A new form of Web content that is meaningful to computers will unleash a revolution of new possibilities". Scientific American. 284 (5): 34–43. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0501-34. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013.

- John Hebeler (April 13, 2009). Semantic Web Programming. ISBN 978-0470418017.

- Segaran, Toby; Evans, Colin; Taylor, Jamie (July 24, 2009). Programming the Semantic Web. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0596153816.

- Lacy, Lee W. (2005). "Chapter 10". OWL: Representing Information Using the Web Ontology Language. Victoria, BC: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-3448-7.

- Baader, Franz; Horrocks, Ian; Sattler, Ulrike (2005). "Description Logics as Ontology Languages for the Semantic Web". In Hutter, Dieter; Stephan, Werner (eds.). Mechanizing Mathematical Reasoning: Essays in Honor of Jörg H. Siekmann on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday. Heidelberg, DE: Springer Berlin. ISBN 978-3-540-25051-7.

- Horrocks, Ian; Patel-Schneider, Peter F.; van Harmelen, Frank (2003). "From SHIQ and RDF to OWL: the making of a Web Ontology Language". Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web. 1 (1): 7–26. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.2.7039. doi:10.1016/j.websem.2003.07.001.

- World Wide Web Consortium (2010-02-06). "W3C Semantic Web Activity". Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- World Wide Web Consortium (2002-08-23). "Metadata Activity Statement". World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- World Wide Web Consortium (2002-08-23). "RDF Vocabulary Description Language 1.0: RDF Schema". RDF Vocabulary Description Language 1.0. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- Lacy, Lee W. (2005). "Chapter 9 - RDFS". OWL: Representing Information Using the Web Ontology Language. Victoria, BC: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-3448-7.

- "Web-Ontology (WebOnt) Working Group (Closed)". W3C.

- Patel-Schneider, Peter F.; Horrocks, Ian (2006-12-19). "OWL 1.1 Web Ontology Language". World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- Grau, B. C.; Horrocks, I.; Motik, B.; Parsia, B.; Patel-Schneider, P. F.; Sattler, U. (2008). "OWL 2: The next step for OWL" (PDF). Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web. 6 (4): 309–322. doi:10.1016/j.websem.2008.05.001.

- Herman, Ivan. "Why OWL and not WOL?". Tutorial on Semantic Web Technologies. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- "Re: NAME: SWOL versus WOL". message sent to W3C webont-wg mailing list on 27 December 2001.

- Ian Horrocks (2012). "Ontologe Reasoning: The Why and The How" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- "OWL: the original". July 7, 2003. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Wang, T. D.; Parsia, B.; Hendler, J. (2006). "A Survey of the Web Ontology Landscape". The Semantic Web - ISWC 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 4273. p. 682. doi:10.1007/11926078_49. ISBN 978-3-540-49029-6.

- Gruber, Tom (1993); "A Translation Approach to Portable Ontology Specifications", in Knowledge Acquisition, 5: 199-199

- W3C (ed.). "OWL Web Ontology Language Guide".

- Patel-Schneider, Peter F.; Horrocks, Ian; Patrick J., Hayes (2004-02-10). "OWL Web Ontology Language Semantics and Abstract Syntax". World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Bechhofer, Sean; Patel-Schneider, Peter F.; Turi, Daniele (2003-12-10). "OWL Web Ontology Language Concrete Abstract Syntax". University of Manchester. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Motik, Boris; Patel-Schneider, Peter F.; Parsia, Bijan (2009-10-27). "OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Structural Specification and Functional-Style Syntax". OWL 2 Web Ontology Language. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- A. Swartz (September 2004). "application/rdf+xml Media Type Registration (RFC3870)". IETF. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2013-09-17. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Patel-Schneider, Peter F.; Motik, Boris (2009-10-27). "OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Mapping to RDF Graphs". OWL 2 Web Ontology Language. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Motik, Boris; Parsia, Bijan; Patel-Schneider, Peter F. (2009-10-27). "OWL 2 Web Ontology Language XML Serialization". OWL 2 Web Ontology Language. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Horridge, Matthew; Patel-Schneider, Peter F. (2009-10-27). "OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Manchester Syntax". W3C OWL 2 Web Ontology Language. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Hitzler, Pascal; Krötzsch, Markus; Parsia, Bijan; Patel-Schneider, Peter F.; Rudolph, Sebastian (2009-10-27). "OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Primer". OWL 2 Web Ontology Language. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Sikos, Leslie F. (2017). Description Logics in Multimedia Reasoning. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54066-5. ISBN 978-3-319-54066-5.

- Brachman, Ronald J. (1983); What IS-A is and isn't: An analysis of taxonomic links in semantic networks, IEEE Computer, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 30-36

- Horrocks, Ian; Patel-Schneider, Peter F. "Reducing OWL Entailment to Description Logic Satisfiability" (PDF).

- Hitzler, Pascal; Krötzsch, Markus; Rudolph, Sebastian (2009-08-25). Foundations of Semantic Web Technologies. CRCPress. ISBN 978-1-4200-9050-5.

- McGuinness, Deborah; van Harmelen, Frank (2004-02-10). "OWL Web Ontology Language Overview". W3C Recommendation for OWL, the Web Ontology Language. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Hayes, Patrick (2004-02-10). "RDF Semantics". Resource Description Framework. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Patel-Schneider, Peter F.; Hayes, Patrick; Horrocks, Ian (2004-02-10). "OWL Web Ontology Language Semantics and Abstract Syntax Section 5. RDF-Compatible Model-Theoretic Semantics". W3C Recommendation for OWL, the Web Ontology Language. World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Mazzocchi, Stefano (2005-06-16). "Closed World vs. Open World: the First Semantic Web Battle". Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Lacy, Lee W. (2005). "Chapter 12". OWL: Representing Information Using the Web Ontology Language. Victoria, BC: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-3448-7.

- OBO Technical WG. "The OBO Foundry". The OBO Foundry. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- "OBO Download Matrix". Archived from the original on 2007-02-22.

- "GBIF Community Site: Section 1: a review of the TDWG Ontologies". Community.gbif.org. 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- "PROV-O: The PROV Ontology". W3.org. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- "PROV-DM: The PROV Data Model". W3.org. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- "protégé". Protege.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- Noy, Natasha; Rector, Alan (2006-04-12). "Defining N-ary Relations on the Semantic Web". World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

Further reading

- Bechhofer, Sean; Horrocks, Ian; Patel-Schneider, Peter F. (2003). "Tutorial on OWL". University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 2017-07-15.

- Franconi, Enrico (2002). "Introduction to Description Logics". Free University of Bolzano.

- Horrocks, Ian (2010). Description Logic: A Formal Foundation for Ontology Languages and Tools, Part 1: Languages (PDF). SemTech 2010.

- Horrocks, Ian (2010). Description Logic: A Formal Foundation for Ontology Languages and Tools, Part 2: Tools (PDF). SemTech 2010.