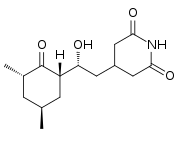

Cycloheximide

Cycloheximide is a naturally occurring fungicide produced by the bacterium Streptomyces griseus. Cycloheximide exerts its effects by interfering with the translocation step in protein synthesis (movement of two tRNA molecules and mRNA in relation to the ribosome), thus blocking eukaryotic translational elongation. Cycloheximide is widely used in biomedical research to inhibit protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells studied in vitro (i.e. outside of organisms). It is inexpensive and works rapidly. Its effects are rapidly reversed by simply removing it from the culture medium.[1]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-[(2R)-2-[(1S,3S,5S)-3,5-Dimethyl-2-oxocyclohexyl]-2-hydroxyethyl]piperidine-2,6-dione | |

| Other names

Naramycin A, hizarocin, actidione, actispray, kaken, U-4527 | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.578 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H23NO4 | |

| Molar mass | 281.352 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless crystals |

| Melting point | 119.5 to 121 °C (247.1 to 249.8 °F; 392.6 to 394.1 K) |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Highly toxic |

| Safety data sheet | Oxford MSDS |

| GHS pictograms |  |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Due to significant toxic side effects, including DNA damage, teratogenesis, and other reproductive effects (including birth defects and toxicity to sperm[2]), cycloheximide is generally used only in in vitro research applications, and is not suitable for human use as a therapeutic compound. Although it has been used as a fungicide in agricultural applications, this application is now decreasing as the health risks have become better understood.

Because cycloheximide rapidly breaks down in a basic environment, decontamination of work surfaces and containers can be achieved by washing with a non-harmful alkali solution such as soapy water or aqueous sodium bicarbonate.

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[3]

Discovery

Cycloheximide was reported in 1946 by Alma Joslyn Whiffen-Barksdale at the Upjohn Company.[4]

Experimental applications

Cycloheximide can be used as an experimental tool in molecular biology to determine the half-life of a protein. Treating cells with cycloheximide in a time-course experiment followed by western blotting of the cell lysates for the protein of interest can show differences in protein half-life. Cycloheximide treatment provides the ability to observe the half-life of a protein without confounding contributions from transcription or translation.

It is used as a plant growth regulator to stimulate ethylene production. It is used as a rodenticide and other animal pesticide. It is also used in media to detect unwanted bacteria in beer fermentation by suppressing yeasts and molds growth in test medium.

The translational elongation freezing properties of cycloheximide are also used for ribosome profiling / translational profiling. Translation is halted via the addition of cycloheximide, and the DNA/RNA in the cell is then nuclease treated. The ribosome-bound parts of RNA can then be sequenced.

Cycloheximide has also been used to make isolation of bacteria from environmental samples easier.[5]

Spectrum of fungal susceptibility

Cycloheximide has been used to isolate dermatophytes and inhibit the growth of fungi in brewing test media. The following represents susceptibility data for a few commonly targeted fungi:[6]

- Candida albicans: 12.5 μg/ml

- Mycosphaerella graminicola: 47.2 μg/ml – 85.4 μg/ml

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: 0.05 μg/ml – 1.6 μg/ml

- Neoscytalidium dimidiatum is an Athlete's foot like infection resistant to most antifungals but is rather sensitive to cycloheximide, so, it should be cultured in a medium free of cycloheximide.

See also

References

- Müller, Franz; Ackermann, Peter; Margot, Paul (2012). "Fungicides, Agricultural, 2. Individual Fungicides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.o12_o06.

- "TOXNET". toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF) (July 1, 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - New York Botanical Gardens. "Alma Whiffen Barksdale Records (RG5)". nybg.org. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Sands, DC; Rovira AD. "Isolation of Fluorescent Pseudomonads with a Selective Medium". Applied Microbiology, 1970, Vol 20 No. 3, p513-514

- "Cycloheximide – The Antimicrobial Index Knowledgebase – TOKU-E". antibiotics.toku-e.com.