Crispijn van de Passe the Younger

Crispijn (van) de Passe (born 1594/1595 in Cologne — buried 19 January 1670 in Amsterdam), also known as Crispijn (van) de Passe the Younger (Dutch: Crispijn (van) de Passe de Jonge) or Crispijn (van) de Passe (II), was a Dutch Golden Age engraver, draughtsman and publisher of prints. [1] He was a member of the large printmaking Van de Passe family, son of the engraver and print publisher Crispijn van de Passe the Elder.

_-_Backgammon_Players_-_WGA17064.jpg)

Work

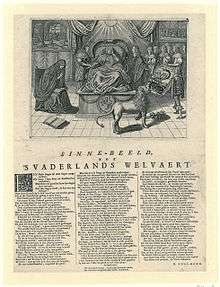

Originally close to his father in artistic style, he began to develop a remarkably fine, sketch-like use of the burin in the 1620s. He produced portraits of a number of prominent European royals and nobles, including the French royal couple Louis XIII of France and Marie de' Medici. He also portrayed Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange and other prominent members of Dutch society, such as Gerardus Vossius, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt and Piet Hein.[2][3]

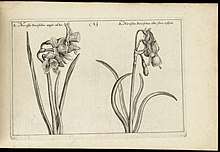

In addition to portraits, he produced engravings of Biblical and historical themes and book illustrations. He created 60 engravings for an influential work on dressage, Maneige royal by Antoine de Pluvinel (Paris, 1623), later published under the title L'Instruction du Roy en l'exercice de monter à cheval. Van de Passe's own Hortus Floridus, published in 1614—1616, was a collection of 160 engravings depicting flowering plants. The work was so popular that the original Latin edition was translated into Dutch, French and English.[2] His Les vrais pourtraits de quelques unes des plus grandes dames da la chrestiente (1640)[note 1] contained two verses dedicated to his sister, the engraver Magdalena van de Passe, who had died two years earlier[4]. In 1643—1644 Joan Blaeu published Van de Passe's Van 't Licht der teken en schilderkonst.[note 2], a book teaching drawing techniques[5].

Prints and other works by Van de Passe are in the collections of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the National Portrait Gallery in London and the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen, among others.

Biography

Van de Passe was a son of engraver and print publisher Crispijn van de Passe the Elder (1564—1637), a Mennonite from Zeeland who had fled from Antwerpen to Germany, and Magdalena de Bock (died in 1635). Van de Passe was born during the period (1589—1611) when the family lived in Cologne. In 1611, the family was forced to leave Cologne and moved to Utrecht, where he, along with his brothers Simon (1595—1647) and Willem (c. 1597—c. 1637) and sister Magdalena (1600—1638) learned the art of engraving in their father's workshop.[4]

Other than his siblings, Van de Passe focused on France rather than England. He was active in Paris from 1618 to 1630, when he returned to Utrecht. In 1639, he spent some time in Delft and Copenhagen before settling in Amsterdam, where he remained until his death in 1670.[1][6]

In 1648 he married Geertraut van dem Brauch, also known as Geertruyt van den Broeck, who hailed from the German town of Solingen. Van de Passe found little success as an engraver in Amsterdam and died in poverty. He was buried in Amsterdam on 19 January 1670.[7]

Notes

- The work was translated into Dutch under the title Ware afbeeldinghe van eenige der aldergrootste ende doorluchtigste vrouwen van heel christenrijck, vertoont in gedaente als herderinnen.

- A facsimile edition with the introduction by J. Bolten was published in 1973 by Davaco Publishers.

References

- "Crispijn de Passe (II)", RKD

- "(van) Crispijn de Passe", The Concise Grove Dictionary of Art, Oxford University Press, 2002 (archived)

- "2012 July Book of the Month", Edward Worth Library

- Ilja Veldman, "Passe, Magdalena de", in: Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland (Dutch)

- Eric Jan Sluijter, Rembrandt and the Female Nude, Amsterdam University Press, 2006

- "Crispijn de Passe the Younger (1594-circa 1670), Printmaker", National Portrait Gallery

- "Crispyn de Passe II", ECARTICO, University of Amsterdam

Further reading

- Ilja M. Veldman, "Een riskant beroep, Crispijn de Passe de Jonge als producent van nieuwsprenten", in Jan de Jong, Mark Meadow, Bart Ramakers en Frits Scholten (ed.), Prentwerk/Print Work, 1500-1700, Zwolle, 2002, pp. 155-185 (Dutch)

- llja M. Veldman, Crispijn de Passe and his Progeny (1564-1670), Studies in prints and printmaking, vol. 3. Rotterdam: Sounds & Vision Publ., 2001

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crispijn van de Passe (II). |