Cranid

CranID was created in 1992 by anthropologist Richard Wright of the University of Sydney to infer the probable geographic origin of unknown crania that are found in archaeological, forensic and repatriation cases. Wright created the program to establish uniformity in cranial morphology based on the assumption that there is a high correlation between geographical location and cranial morphology. This was the first standardized program to evaluate the similarity and dissimilarity of cranial morphological characteristics of an unknown cranium and the database.[1]

Software

CranID is a free software program that utilizes multivariate linear discriminant analysis and nearest neighbor discriminant analysis in conjunction with 29 cranial measurements to assess the geographic origin, which can be used to infer the ancestry of an unknown cranium. CranID compares an unknown cranium with 74 geographic samples, from 3,163 crania from 39 different populations.[2]

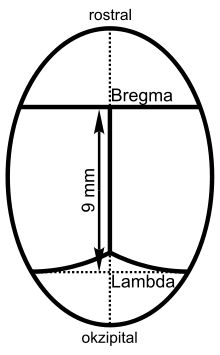

The measurements and landmarks used in this program to compare an unknown cranium with the database consist of glabello-occipital length, nasio-occipital length, basion-nasion length, basion-bregma height, maximum cranial breadth, maximum frontal breadth, biauricular breadth, biasterionic breadth, basion-prosthion length, nasion-prosthion height, nasal height and breadth, orbit height and breadth, bijugal breadth, palate breadth, bimaxillary breadth, zypomaxillary subtense, bifrontal breadth, nasio-frontal subtense, biorbital breadth, interorbital breadth, cheek height, frontal chord, nasion-bregma subtense (frontal subtense), parietal chord, bregma-lambda subtense (parietal subtense), occipital chord and lambda-opisthion subtense (occipital subtense). Each cranial measurement and their definitions were taken from W.W. Howells' data set.[3]

Data Set

The program compares unknown crania to 74 geographical samples that are from a collection of 3,163 crania from 39 different populations from around the world. This data set consists of W.W. Howells' 1973 study of cranial variation of 2,524 crania from 28 populations from around the world.[4] This database also consists of measurements from Beduin crania provided by Martha Lahr, samples of measurements collected from Poundbury, a Romano-British 4th century AD site, and measurements from the Iron Age in Palestine and the Indian Subcontinent, provided by London’s Natural History Museum. Wright also added cranial measurements from Australian Aborigines form the Sydney area, which were provided by the La Perouse Aboriginal Land Council in conjunction with the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council. The data set also consists of cranial measurements from India, provided by P. Reghavan and D. Bulbeck, crania from Southern Italy, and Neolithic crania from Denmark, that were provided later by R. Kruszynski of the Natural History Museum, and P. Bennike of the Pranum Institute respectively.[5]

Uses

This program is used to determine geographical origin of skeletal remains in archaeological and forensic contexts. Due to the geographical origin of the program and the author of the program, and the many crania included in the data set, this program is mainly used by Australian and British bioarchaeologists and forensic anthropologists. Forensic anthropologists use this software to determine the ancestry of unknown skeletal remains, in medico-legal contexts. The use of this program is designed to aid forensic anthropologists in the determination of the biological profile, which includes factors such as age, sex, stature and race. This biological profile is used to determine personal identification of skeletal remains from crime scenes, car and plane accidents, and mass disasters.[6]

Bioarchaeologists use this program in the same way as forensic anthropologists, but in more of an archaeology context. Determining ancestry in an archaeological context allows the researcher to build information on the skeletal remains that are found in archaeological burials, which aids in the development of knowledge of the culture and its practices and customs. This program is also used by many bioarchaeologists to conduct bio distance studies of skeletal remains, by comparing craniometric measurements of found archaeological remains with craniometric measurements of known skeletal remains from medical and legal institutions.[7]

Criticisms

Although the maker of CranID does not explicitly state that this program can infer ‘race’, many forensic anthropologists use this program, and others like it, to determine the race of an unknown individual, even though many biological anthropologists have criticized the use of the concept. A study conducted on the CranID program found that while the program is "supposed to allocate an individual skull to a specific population rather than a ‘major race’," the program did not generate persuasive allocations of individual crania to a geographical population.[8]

Another criticism is the fact that many of the measurements that are essential to this program are subject to both interobserver error and intraobserver error. Measurements between researchers can vary substantially in size and that this degree of variation in measurements can have a striking effect on the results of CranID. Due to this potential error, the results of CranID should be taken into account when assessing how accurate any findings formed by CranID are.[9]

Although the combined data set that CranID utilizes includes many geographical regions, there are still many regions that are not accounted for in this data set. According to Fenja Theden-Ringl and colleagues, the use of CranID and another forensic anthropology software program, FORDISC, were unable to place skeletal remains from two site found in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory of Australia. The researchers believe that both these programs were unable to accurately assign the skeletal remains to any group due to both programs lacking Indonesian data in the databases that are used by these programs.[10]

See also

References

- Kallenberger, Lauren; Pilbrow, Varsha (2012). "Using CRANID to Test the Population Affinity of Known Crania". Journal of Anatomy. 221 (5): 459–464. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01558.x. PMC 3482354. PMID 22924771.

- Hughes, S., Wright, R., Barry, M. "Virtual Reconstruction and Morphological Analysis of the Cranium of an Ancient Egyptian Mummy." Australasian Physical & Engineering Sciences in Medicine. Volume 28 (2005).

- Cox, Margaret. The Scientific Investigation of Mass Graves: Towards Protocols and Standard Operating Procedures. Cambridge University Press 2008.

- Howells, WW. (1995). Who’s Who in Skulls. Ethnic Identification of Crania from Measurements. Cambridge, Mass.: Peabody Museum.: Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. pp. vol. 82, pp. 108.

- Wright R. Guide to Using the CRANID6 Programs CR6aIND: For Linear and Nearest Neighbours Discriminant Analysis. 2010. Available: http://www.box.net/shared/static/n9q0zgtr1y%5B%5D. EXE

- Ousley, Stephen; Jantz, Richard; Freid, Donna (2009). "Understanding Race and Human Variation: Why Forensic Anthropologists are Good at Identifying Race". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139: 68–76. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21006. PMID 19226647.

- Perera, C.; Christopher, B.; Weerasooriya, T.; Stephen, C. (2007). "Assessment of Ethnicity By Comparison of Multiple Craniometric Data: A Preliminary Study". Galle Medical Journal. 12 (1).

- Sierp, Ingrid; Henneberg, Maciej (2015). "Can ancestry be consistently determined from the skeleton?". Anthropological Review. 78 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1515/anre-2015-0002.

- Smith, Martin J. A Study of Interobserver Variation in Cranial Measurements and the Resulting Consequences when Analysed Using CranID. Proceedings of the 12th Annual Conference of the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology British Archaeological Reports, International Series 2380, Edited by Buckberry J., Mitchell P.D., 01/2012; Archaeopress. ISBN 9781407309705

- Theden-Rignl, Fenja; Fenner, Jack N.; Wesley, Daryl; Lamilami, Ronald (December 2011). "Buried on Foreign Shores: Isotope Analysis of the Origin of Human Remains Recovered from a Macassan Site in Arnhem Land". Australian Archaeology. 12 (1).

Further reading

- Cross, Pamela J., Wright, R. "The Nikumaroro bones identification controversy: First-hand examination versus evaluation by proxy-- Amelia Earhart found or still missing?" Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. Volume 3, Pages 52–59, September 2015

- Navajo, David, Catarina Coelho, Ricardo Vicente, Maria Teresa Ferreira, Sofia Wasterlain, Eugenia Cunha. "AncesTrees: Ancestry Estimation with Randomized Decision Trees". International Journal of Legal Medicine. Volume 129, July 2014.

- Lockyer, Nicholas. "3D ID: An Assessment of its Utility, and an Analysis of the Potential of 3D Geometric Morphometrics in Ancestry Determination from the Skull." AXIS, Volume 2, Issue 1, Summer 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20151124173235/https://ojs.lifesci.dundee.ac.uk/index.php/Axis/article/viewArticle/62