Couvent des Feuillants

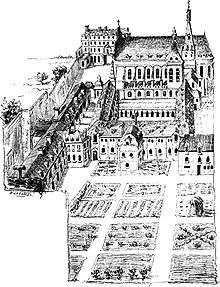

The royal monastery of Saint-Bernard, better known as the Couvent des Feuillants or Les Feuillants Convent, was a Feuillant nunnery or convent in Paris, behind what is now numbers 229—235 rue Saint-Honoré, near its corner with rue de Castiglione. It was founded in 1587 by Henry III of France. Its church was completed in 1608 and dedicated to Saint Bernard of Clairvaux.

To the left, the alignment of the buildings and the passage along the cloister wall correspond to the axis of the present-day rue de Castiglione. The central path through the garden, at right angles to this axis, corresponds to the line of the present-day rue du Mont-Thabor.

- Not to be confused with Les Feuillants Abbey.

The nunnery was secularised and nationalised in the decrees of 13 and 16 May 1790 and became notable as the meeting place of the Feuillant Club. Jacques-Louis David used the nave of the convent's church as a studio for his painting The Tennis Court Oath. Most of the complex was then demolished under the French Consulate, leaving only the guesthouses at 229—235 rue Saint-Honoré (built in 1776 by Jacques Denis Antoine and classed as a historic monument in 1987[1]) and the outline of its church's apse, which can be discerned in the courtyard of one of the guesthouses.

History

.jpg)

Foundation

Between the end of the 16th and the start of the 17th centuries, several Catholic Reformation and Counter Reformation religious orders set up complexes in the district below the second porte Saint-Honoré. They were most often set up on royal initiative, such as the Capuchin house set up by Catherine de Medici in 1576 in the Tuileries Palace, close to the district. Not ten years later, in 1585, Henry III acquired the hôtel des Carneaux,[N 2] whose buildings and lands bordered those of the Capuchins, to set up a new convent. At first he intended it to be a Hieronymite house, but he later switched this to sixty members of the Feuillant order from Toulouse. They arrived in the outskirts of Paris on 11 July 1587 and moved into the convent on 8 September the same year.[2]:8

The convent buildings were designed by the king's architect Baptiste Androuet du Cerceau,[3]:300 and construction work was led by one of the monks.[4]:483–486

Development

Abbot Jean de La Barrière remained loyal to Henry III, preaching his funeral oration at Bordeaux, but several of his disciples joined the Catholic League.[2]:8 At the end of the French Wars of Religion the convent held only nine monks,[5]:86 but still benefited from royal patronage after the war's end.

By letters patent of 20 June 1597,[5]:86 Henry IV of France put the convent under his protection and granted it all the privileges owing to a royal foundation. On 25 August the same year, he enlarged its lands by adding a house beside the couvent des Capucins which Henry III had acquired from the duc de Retz. Henry IV promised the convent the revenues from the rich Val Abbey in commend, though that promise was realised only by his successor Louis XIII.[2]:11

The convent church was also completed during Henry IV's reign, in 1608, thanks to the alms given in the holy year of 1600. It was dedicated to Bernard of Clairvaux and in 1624 gained a monumental façade, paid for by Louis XIII.

In 1621[6]:306, 314 the Feuillants set up their novitiate in the faubourg Saint-Jacques, at what is now 10 rue des Feuillantines. In 1633 that site was given over to a convent of nuns of the same order (known as Feuillantines) to fulfil a vow by Anne of Austria and the novitiate moved to rue d'Enfer (on the site of 91-105 of present-day boulevard Saint-Michel)[6]:306

Besides the revenues from Val Abbey, the Feuillants also enjoyed those of several guesthouses which they bought or built on their lands.[2]:11 One of them, built in 1676, later became the home of Marguerite de la Sablière, who hosted Jean de La Fontaine there.

Under the Constitutional Monarchy

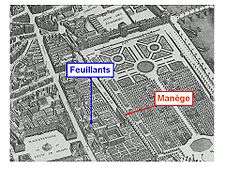

The French Revolution marked a turning point in the convent's life. Decrees on 13 May and 16 July 1790 transferred all church lands, goods and buildings to the nation[7]:582 and so the lands and buildings belonging to the Feuillants were nationalised. The buildings became more and more abandoned by the monks (some of whom housed themselves in the former couvent de la Mercy on rue du Chaume), but were not sold, since they were close to the salle du Manège, where the National Constituent Assembly met from 1791 onwards.[8]:181

The buildings thus housed several offices and committee rooms and for a few months the convent library housed the national archives. These political and administrative functions justified opening the complex to the public, including, merchants, artisans, lemonade sellers and coffee sellers. The place Vendôme section of the National Guard was also based in the complex.[8]:188

The church was also used for secular purposes. Its nave given to the painter Jacques-Louis David in autumn 1791 to paint his The Tennis Court Oath, not only since it could be adapted to fit the huge canvas but also due to its proximity to the Assembly, where several of its sitters were deputies.[9]:58 He placed an announcement in Le Moniteur asking deputies who had been present to the event to come to have their likeness engraved.[9]:68

The complex's proximity to the Assembly also meant that a club was set up in the old convent buildings - this became known as the Feuillants Club. Its members were dissidents from the "Society of Friends of the Constitution", more popularly known as the Jacobin Club after its meeting place in the former couvent des Jacobins on rue Saint-Honoré. The split had led to the Champ de Mars Massacre on 17 July 1791, marking the people's defiance to a king who had tried to flee. Opposed to supporters of Louis XVI's fall, the more moderate members of the Jacobin Club left it and set up a "Society of Friends of the Constitution Sitting at Les Feuillants", made up of supporters of the constitutional monarchy. The presence of this political club so close to the Assembly's meeting place led to a strong parliamentary polemic in December 1791.[7]:819

The Feuillants Club disappeared with the constitutional monarchy it supported on 10 August, when Louis XVI and his family were arrested - the royal family were housed at the convent before their transfer to the prison du Temple on 13 August.[7]:582

First Republic

In 1793, the National Convention moved from the Manège and les Feuillants to the Tuileries. In the autumn, the old convent buildings became factories and administration buildings for arms manufacture. The artillery museum was also set up there before being moved to the couvent des Jacobins in 1796.

Under the French Consulate, the decrees of 17-vendémiaire and 1-floréal in year X (9 October 1801 and 21 April 1802) put into effect part of the works planned in the "Plan des Artistes",[10]:140 ordering the creation of what would become rue de Rivoli and rue de Castiglione over the Feuillants convent site. The convent was thus totally demolished, except for the guesthouses on rue Saint-Honoré (numbers 229-235) and the apse of the church, whose outline can be seen in one of the guesthouses' courtyard.

Buildings

Rue Saint-Honoré

The entrance gateway, probably built by Jean Richer to a design by Libéral Bruand,[11] was built between 1676[12] et 1677.[11] It was a large gateway surmounted by a bas-relief and surrounded by paired columns supporting a triangular pediment containing the arms of France and Navarre. The bas-relief was by Anguier and showed Henry IV presenting the monks with plans of the church.[N 1]

In the 18th century, this classical gateway formed the focal point of place Louis le Grand (now place Vendôme), opposite the gateway of the new couvent des Capucines on the opposite side. It gave access to a courtyard in front of the church and to a passage linking the convent to the stables of the Tuileries and the 'terrasse des Feuillants'. This passage was later enlarged to form rue de Castiglione, whose construction led to the destruction of the gateway.

To the left of the gateway and to the east of the corner of the present rue de Castiglione were convent buildings (on the site now numbered as 229-235 rue de Castiglione) built between 1776 and 1782 by Jacques Denis Antoine. It was one of the main guesthouses belonging to the convent and still exists, its central body surmounted by a semi-circular pediment corresponding to number 231 and now inscribed on the historic monuments list.[13]

Present-day numbers 229-235, rue Saint-Honoré : Guesthouse designed by Antoine for the Feuillants.

Present-day numbers 229-235, rue Saint-Honoré : Guesthouse designed by Antoine for the Feuillants. Central building of the guesthouse (now number 231).

Central building of the guesthouse (now number 231). Borne de la ville de Paris in front of number 229.

Borne de la ville de Paris in front of number 229.

Church of Saint-Bernard

Exterior: Mansart façade

Convent buildings, cloister and gardens

Notes

- Thiéry 1787, p. 109 and Aubin Louis Millin 1790, p. 11, who attribute the bas-relief to Jean Goujon (although the sculptor probably died even before the convent's foundation), argue that it showed Henri III and Jean de La Barrière. However an engraving published by Millin (portfolio X, no 1) shows that it was Henry IV rather, launching building work on the church around 1601. A model of the bas-relief was held in the convent library.

- According to Biver & Biver 1970, p. 84, 'Carneaux' derives from 'créneaux', meaning an old fortified house.

References

- Page on base Mérimée

- Millin 1790

- Berty 1866

- Sauval 1724

- Biver & Biver 1970

- Hillairet 1956

- Tulard, Fayard & Fierro 1987

- Soboul 1972

- Sahut & Michel 1988

- Jacques & Mouilleseaux 1988

- (Biver & Biver 1970, p. 87).

- (Thiéry 1787, p. 109).

- http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/merimee_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_1=REF&VALUE_1=PA00085792

Sources

- Berty, Adolphe (1866). Topographie historique du vieux Paris. Région du Louvre et des Tuileries. vol I. Paris: Imprimerie imperial.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Biver, Paul; Biver, Marie-Louise (1970). Abbayes, monastères et couvents de Paris: des origines à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Éditions d'histoire et d'art, Nouvelles éditions latines. pp. 76–98.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brette, Armand (1902). Histoire des édifices où ont siégé les assemblées parlementaires de la Révolution française et de la première République. vol I. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. pp. 275–286.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ciprut, Édouard-Jacques (1957). "L'église du couvent des Feuillants, rue Saint-Honoré. Sa place dans l'architecture religieuse du XVIIe siècle". Gazette des Beaux-Arts. vol. L. pp. 37–52.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hillairet, Jacques (1956). Connaissance du Vieux Paris. Éditions de Minuit/Le Club Français du Livre. pp. 9–10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacques, Annie; Mouilleseaux, Jean-Pierre (1988). Les architectes de la liberté. Collection "Découvertes Gallimard". vol 47. Gallimard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Millin, Aubin Louis (1790). "Les Feuillans de la rue Saint-Honoré". Antiquités nationales. vol I. Paris: Drouhin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sahut, Marie-Catherine; Michel, Régis (1988). David, l'art et le politique. Collection "Découvertes Gallimard". vol 46. Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-053068-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sauval, Henri (1724). Histoire et recherches des antiquités de la ville de Paris. vol I. Paris: Moette et Chardon. pp. 483–486.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Soboul, Albert (1972). Précis d'histoire de la révolution française. Paris: Éditions sociales.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thiéry, Luc-Vincent (1787). Guide des amateurs et des étrangers voyageurs à Paris. vol 1. Paris: Hardouin et Gattey.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tulard, Jean; Fayard, Jean-François; Fierro, Alfred (1987). Histoire et dictionnaire de la révolution française, 1789–1799. Paris: Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-04588-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)