Council of Europe Convention on the Counterfeiting of Medical Products

The Council of Europe Convention on the Counterfeiting of Medical Products and Similar Crimes involving Threats to Public Health (or MEDICRIME Convention)[1] is an international criminal law convention of the Council of Europe addressing the falsification of medicines and medical devices.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

| Signed | 28 October 2011 |

| Location | Moscow, Russian Federation |

| Effective | 1 January 2016 |

| Condition | 5 ratifications, including at least 3 Council of Europe member states |

| Signatories | 16 signatures and 16 ratifications |

| Parties | 16 (as of October 2019) |

| Depositary | Secretary General of the Council of Europe |

| Languages | French and English |

Background

The falsification of medicines and medical devices is an extremely profitable, low-risk form of crime, even in comparison with drug trafficking. These crimes endanger people’s health and lives, and thus may even violate the right to life enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights. They also undermine public trust in health-care systems and health surveillance authorities.

History

The convention was adopted by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe in 2010, and opened for signature at a high-level conference organised in Moscow on 28 October 2011.[2] Its official texts are in English and French, which are equally authentic.[3] Other translations in non-official languages are also available,[4] but they are for information purposes only.

To date, the MEDICRIME Convention is the only international legal instrument providing the means to criminalise the falsification of medical products.

Products covered by the convention

Medicines for human and veterinary use, ingredients, parts and materials used in the production of medicines, medical devices, accessories and clinical trial medicines.

Key provisions

The treaty contains 33 articles, organised in three fundamental pillars:

- criminalising the falsification of medicines and medical devices;

- protecting victims’ rights;

- encouraging national and international co-operation.

As a criminal law instrument, the convention does not deal with unintentional quality defects[5] and it does not deal with the violation of intellectual property rights. It may use the term “counterfeit” meaning a “false representation as regards identity and/or source", but “falsification” is preferred as Medicrime is solely about protecting public health.

Criminalising the falsification of medicines and medical devices

The convention criminalises certain acts because dangerous to public health. Only intentional acts are punishable offences.

- Article 5 stipulates that the intentional manufacturing of falsified medical products, active substances, excipients, parts, materials and accessories is a criminal offence.

- Article 6 provides that the intentional supplying (brokering, procuring, selling, donating or offering for free and promoting), keeping in stock, importing and exporting of falsified medical products, active substances, excipients, parts, materials and accessories are criminal offences.

- Article 7 specifies that intentionally producing false documents and tampering with existing ones are criminal offences.

- Article 8 establishes offences that are considered similar to falsification because they pose a serious threat to public health, such as intentionally manufacturing or placing medicinal products on the market without authorisation,[6][7] including medical devices that fail to comply with conformity requirements.[8][9]

Protecting victims’ rights

The convention reinforces victim’s rights by ensuring that they have access to all information relevant to their case, assisting them in their recovery and providing for their compensation, among others. Victims are not required to file charges or prove any harm suffered for an investigation to be opened – the risk of a threat to health is sufficient to this end.

Encouraging national and international co-operation

Co-operation at national and international level is an important aspect of the convention. Given the wide range of stakeholders confronted with the increasing prevalence of such crimes, from health authorities and law-enforcement agencies to customs services and the judiciary, synergies and co-operation among them should be promoted and facilitated. States parties to the convention are encouraged to set up a mechanism enabling the smooth exchange of information and co-operation within and across borders.

Universality of the convention

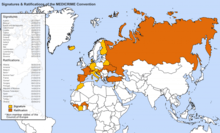

Although drafted by a European institution, this convention is also open for signature and ratification[10] by non-European countries. Given the international – even intercontinental – scope of this type of crime, addressing the global dimension of this phenomena is imperative.

State Parties to the MEDICRIME Convention[10][11]

As of September 2019, there are 16 State Parties to the Convention on the Falsification of Medical Products and Similar Crimes involving Threats to Public Health: Albania, Armenia, Belgium, Benin, Burkina Faso, Croatia, France, Guinea, Hungary, Portugal, the Republic of Moldova, the Russian Federation, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and Ukraine. Another 16 countries have signed but not ratified it.

In July 2017, Burkina Faso became the 10th country to ratify the convention, triggering the establishment of the Committee of the Parties. This committee is the convention’s monitoring body and is tasked with facilitating the implementation and follow-up of the convention in the state parties. Its first meeting took place in December 2018.

See also

References

- "MEDICRIME Convention". Council of Europe Treaty Office. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Remarks by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov at the Opening for Signature Ceremony of the Council of Europe Convention on Falsification of Medical Products and Similar Crimes involving Threats to Public Health (Medicrime Convention), Moscow, October 28, 2011". www.mid.ru. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Translations". Council of Europe Treaty Office. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Official and non-official languages". Council of Europe Treaty Office. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Quality defects and recalls". European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "The European regulatory system for medicines", European Medecines Agency. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "The Drug Development Process". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Conformity assessment". European Commission – Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "CE marking". European Union – Your Europe. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Chart of signatures and ratifications of Treaty 211". Council of Europe Treaty Office. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- "Treaty Office Glossary". Council of Europe Treaty Office. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

External links

The MEDICRIME Convention – Latest news

The MEDICRIME Convention – Background

Fondation Chirac: "La Convention MÉDICRIME entre en vigueur !"