Coryat's Crudities

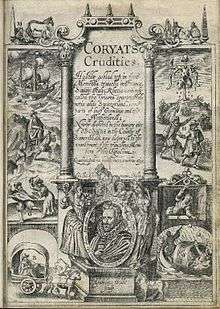

Coryat's Crudities: Hastily gobled up in Five Moneth's Travels is a travelogue published in 1611 by Thomas Coryat of Odcombe, an English traveller and mild eccentric.

History

The book is an account of a journey undertaken, much of it on foot, in 1608 through France, Italy, Germany, and other European countries. Coryat (sometimes also spelled "Coryate" or "Coriat") conceived of the 1,975-mile (3,175 km) voyage to Venice and back in order to write the subsequent travelogue dedicated to Henry, Prince of Wales, at whose court he was regarded as somewhat of a buffoon and jester, rather than the wit and intellectual he considered himself. The extent to which Coryat invited such ridicule in pursuit of patronage and court favor is unclear.[1]

Among other things, Coryat's book introduced the use of the fork to England[2] and, in its support of continental travel, helped to popularize the idea of the Grand Tour that rose in popularity later in the century. The book also included what is likely the earliest English rendering of the legend of William Tell.

The work is particularly important to music historians for giving extraordinary details of the activities of the Venetian School, one of the most famous and progressive contemporary musical movements in Europe. The work includes an elaborate description of the festivities at the church of San Rocco in Venice, with polychoral and instrumental music by Giovanni Gabrieli, Bartolomeo Barbarino, and others.[3]

Crudities was only twice reprinted at the time, so the first edition is quite rare today. Later, "modern" facsimiles were put out, in 1776 and 1905, which included the later trip to Persia & India.

"Commendatory" verses

A custom of Renaissance humanists was to contribute commendatory verses that would preface the works of their friends. In the case of this book, a playful inversion of this habit led to a poetic collection that firstly refused to take the author seriously; and then took on a life of its own. Prince Henry as Coryat's patron controlled the situation; and willy-nilly Coryat had to accept the publication with his book of some crudely or ingeniously false panegyrics. Further, the book was loaded with another work, Henry Peacham's Sights and Exhibitions of England, complete with a description of a perpetual motion machine by Cornelis Drebbel.[4]

Coryat, therefore, was jokingly mocked by a panel of contemporary wits and poets of his acquaintance. At the behest of the teenage prince, a series of verses was commissioned, of which 55 were finally included for publication. The authors of these verses, which included John Donne, Ben Jonson, Inigo Jones, and Sir Thomas Roe, among others, took especial liberties with personal anecdotes, finding Coryat's self-importance a ripe source of humour. The literary men known to Coryate were typically courtiers, or those whom he had met through Edward Phelips of the Middle Temple, a patron from Somerset.[5] A full list of the authors (translated from Latin originals) is given in the margin in a 1905 edition.[6]

- Ἀποδημουντόφιλoς [Greek pseudonym]

- Henry Neville

- John Harrington

- Lewes Lewkenor

- Henry Goodier

- John Payton junior

- Henry Poole

- Robert Phillips

- Dudley Digges

- Rowland Cotton

- Robert Yaxley

- John Strangwayes

- William Clavel

- John Scory

- John Donne

- Richard Martin

- Laurence Whitaker

- Hugo Holland

- Robert Richmond

- Walter Quin

- Christopher Brooke

- John Hoskins

- John Pawlet

- Lionel Cranfield

- John Sutclin

- Inigo Jones

- George Sydenham

- Robert Halswell

- John Gyfford

- Richard Corbet

- John Dones

- John Chapman

- Thomas Campian

- William Fenton

- John Owen

- Peter Alley

- Samuel Page

- Thomas Momford

- Thomas Bastard

- William Baker

- Tὸ Ὀρὸς-ὀξὺ [Greek pseudonym]

- Josias Clarke

- Thomas Farnaby

- William Austin

- Glareanus Vadianus

- John Jackson

- Michael Drayton

- Nicholas Smith

- Laurence Emley

- George Griffin

- John Davis

- Richard Badley

- Jean Loiseau de Tourval

- Henry Peacham

- James Field

- Glareanus Vadianus

- Richard Hughes

- Thomas Coryat

There were poems in seven languages. Donne wrote in an English/French/Italian/Latin/Spanish macaronic language. Peacham's was in what he called "Utopian", which was partly gibberish, and the pseudonymous Glareanus Vadianus (tentatively John Sanford) wrote something close to literary nonsense. The contribution of John Hoskyns is called by Noel Malcolm "the first specimen of full-blown literary English nonsense poetry in the seventeenth century".[5]

Coryat had to take this all in good part. The book appeared with engravings by William Hole, and the author received a pension.[7] Shortly a pirate version of the verses appeared, published by Thomas Thorpe, under the title The Odcombian Banquet (1611).[8]

Modern analogues

British travel writer and humourist Tim Moore retraced the steps of Coryat's tour of Europe, as recounted in his book Continental Drifter.

References

- Pritchard, R.E. (2014) [2004]. Odd Tom Coryate, The English Marco Polo. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0-7524-9514-9.

- Strachan, Michael (2013) [2003]. "Coryate, Thomas (c. 1577-1617)". In Speake, Jennifer (ed.). Literature of Travel and Exploration: an Encyclopedia. Volume 1: A to F. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 285–287. ISBN 978-1-579-58247-0.

- O'Callaghan, Michelle, "Patrons of the Mermaid tavern (act. 1611)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. Accessed 30 Nov 2014.

- Strong, Roy (2000). Henry Prince of Wales and England's Lost Renaissance. Pimlico. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-7126-6509-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malcolm, Noel (1997). The Origins of English Nonsense. HarperCollins. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-0063-8844-9.

- Coryat, Thomas (1905). Coryat's Crudities. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons. pp. 22–121.

- Strong (2000), p. 24

- Kathman, David. "Thorpe, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27385. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Chaney, Edward, "Thomas Coryate", entry in the Grove-Macmillan Dictionary of Art.

- Chaney, Edward (2000). "The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance." 2nd ed. Routledge: London and New York.

- Craik, Katharine A. (2004). "Reading Coryats Crudities (1611)." SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900 44(1): 77-96.

- Penrose, Boies. (1942). Urbane travelers: 1591-1635. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Pritchard, R.E. (2004). Odd Tom Coryate, The English Marco Polo. Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton.

- Strachan, Michael. (1962). The life and adventures of Thomas Coryate. London: Oxford University Press.