Contiomagus

Contiomagus was a Gallo-Roman vicus in the Roman province of Gallia Belgica. The location today is the site of the district of Pachten in the municipality of Dillingen, Saarland.[1][2][3]

Origin

Contiomagus was founded during the colonization phase after Caesar's conquest of Gaul from 58 to 51 BC. The location on the intersecting trunk roads Trier-Straßburg and Metz-Mainz as well as the existence of a ford across the Saar (Saravus) and the proximity to the valleys of Prims and Nied favored the development of Contiomagus. Coin finds indicate that the settlement originated around 10 BC and lasted for 200 years.

The name of the place, "Contiomagus", consists of the Celtic word component "magus" (market) and the short form "Contio" for Condate/Confluentes (confluence). As a "confluence" one must assume the mouth of the Prims into the Saar, located in the immediate vicinity of Contiomagus. A similar name has the place Konz (Contionacum) at the mouth of the Saar into the Moselle.

The route of the Roman road from Metz (Divodurum) to Mainz {Mogontiacum) ran through the Nied valley and crossed the Saar at Contiomagus, continuing along the banks of the Prims and the Theel via Lebach and Tholey to the Rhine. In 244 AD, the crossing of the Saar was improved by the construction of a wooden bridge at Contiomagus. The road from Trier (Augusta Treverorum) to Straßburg (Argentoratum) divided at Zerf. The southern route led from Beckingen along the Saar Valley and went via Contiomagus and Saarbrücken (vicus Saravus) to Straßburg, while the northern route passed through Tholey and Schwarzenacker, then rejoined with the Saar valley route. Both routes were connected via the cross-connections Contiomagus-Tholey and Saarbrücken-Schwarzenacker.

Development

There were already settlements of the Celtic tribe of the Treveri in the vicinity of today's Dillingen, around the Limberg, on the Prims, and at the mouth of the Nied at the arrival of the Romans. A sword from the late La Tène was found in 1967 in Pachten (Leipziger Ring).

In the years 58–51 BC Caesar's troops conquered the area along the Saar. The region was located at the border between the Celtic tribes of the Treveri and the Mediomatrici. The names of the carvings of the "Pachtener Sitzsteine" (seating, presumably from a cult theater) suggest the settlement of both tribes in the Pachten area.

Contiomagus was primarily a trading town. According to the testimony of Ausonius, a court official of Emperor Valentinian I (r.364–375), there was merchant shipping on the Saar. The chief locations were the bridges in Sarrebourg (pons Saravi), Saarbrücken and Pachten (Contiomagus).[4] In the 3rd century, Contiomagus was threatened by the Germans, and 275–276 it was destroyed by the Franks at the beginning of the Migration Period. During reconstruction, a fort was built.

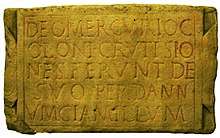

In the Roman Empire, the Civitas of the Treveri, including Pachten, belonged to the province of Belgica Prima, with its provincial capital at Trier. The Treveri gradually assimilated Roman culture, the Celtic language maintained itself in the country well into the 4th century AD. Celtic religion mingled syncretistically with the Roman deities (the "Interpretatio Romana"). The custom of erecting votive stones to the gods was widespread. From Pachten two such stones have been preserved: the Contiomagus Stone and the Merkur Stone. The latter was found in 1847 on the first plowing of a marshy spot in the "Nachtweide". The inscription of the white sandstone sculpture (39 × 23 × 10 cm with a letter height of 3 cm) reads:

DEO MERCVRIO C

OLONI CRVTISIO

NES FERVNT DE

SVO PER DANN

VM GIAMILLVM

Translation: "The coloni of Crutisio had this [stone] erected to the god Mercury by Dannus Giamillus."

In the immediate vicinity lay the shards of urns, jugs and small consecration vessels. Coloni are tenant farmers who depend on a large landowner. From this it follows that at the time of the dedication of the stone a villa must have existed in Pachten or the immediate vicinity. The discovery of the sacred stone led to the assumption that the ancient name of today's Pachten was "Crutisio", but this assumption was refuted by the discovery of the Contiomagus stone.

The Contiomagus stone was found during excavation work October 22, 1955. The stone had been re-used as the foundation stone of a corner tower of the fort of Contiomagus. The grayish-yellow sandstone is 66 × 45 × 28 cm with the height of the inscribed part 46 cm. The upper part of the stone of is broken off and missing. The existing relief piece presumably represents a seated goddess, who is dressed in a tunic, which has strong drapery. To the right of the goddess a small animal, perhaps a dog, is visible to the viewer. The inscription, whose letters have a height of about 4 cm, reads:

. O . D .

. T . PRITONAE . DI

VINAE . SIVE . CA . .

IONI . PRO . SALVTE

VICANORUM . CONTI

OMAGI . ENSIVMTER

TINIUS . MODESTUS

F . C . V . S .

A possible translation might be: "To the divine Pritona or Ca…ioni for the safety of the inhabitants of Contiomagus Tertinius Modestus." Pritona can be interpreted as a river goddess or goddess of trade.

The first and last lines of the dedication are written in abbreviations and heavily weathered. During temporary storage of the find in Saarbrücken it was misused by workmen, out of ignorance, as a support for the processing of building materials and thereby suffered further damage. As a result, the scientific interpretation of the first and last lines is still controversial.

Another indication of the veneration of Mercury in Pechten is the small sculpture of the god from years around the beginning of the 3rd century, discovered in 1961 during the excavation for construction of a factory. Statuettes of other Roman and Egyptian gods were also found. The following centuries brought a period of prosperity for Pachten, expressed by the size of the village and the number of excavation finds, especially in the cemetery.

Long before archaeological research into the history of Pachten was undertaken, the existence of a Roman settlement was known. The Benedictine monk Dom Calmet in his 1757 history of Lorraine (Histoire de Lorraine) has an entry. In the following century, the Saarlouis judicial counselor and notary Nicolas Bernard Motte (Manuscrit tiré des archives même de Sarrelouis et de ses environs) studied Roman Pechten.

The most intense and fundamental research on this period was done by Philipp Schmitt, who served as pastor in Dillingen from 1833 to 1848 (Der Kreis Saarlouis und seine nächste Umgebung unter den Römern und Kelten). During the great drought of 1842 by the growth differential he was able to trace numerous foundations of ancient Pachten's buildings in the meadows of former farming villages. Schmitt estimated a population of about 2000 people for Gallo-Roman Pachten. In 1865 Georg Balzer interpreted some of the foundations discovered by Schmitt as a Roman fort.

In the years 1891 and 1935 systematic excavations of the Landesmuseum Trier took place in Pachten. They discovered an extensive Roman civil settlement between today's railways in the east and the Wilhelmstrasse area. Similarly, a Frankish graveyard was found near the medieval village church, probably in the vicinity of a late Roman burial ground.

The Roman burial ground in the Margarethenstraße was discovered accidentally in 1950 and excavated by the Conservatory of Saarland through the 1960s. The excavations uncovered over 500 graves, each with three to 14 items grave goods. Of particular importance are the terracotta figures, which are probably all from children's graves and are interpreted as toys.

During the construction work following the canalization of the Saar, in the summer of 1985, the remains of a Roman road were discovered that led from the Saar to the fort and the settlement, dating back to the second century AD.

The peace of the Gallo-Roman vicus was severely disturbed by invasions of the Germans beginning in the 3rd century. Pachten was nearly razed to the ground during the invasion of the Franks in 275–6. Burnt layers and buried coin hoards, placed in the ground for safekeeping by the population, point to this troubled era. One such treasure with 4000 coins, probably from the middle of the 3rd century, was found in 1858. In the last third of the 3rd century the construction of a Roman fort led to a revival, which is marked by numerous finds. The fort had a width of 134 m in east-west direction and was 152 m long. The walls were 2.9 m thick. At all four corners were square towers (6.73 m) with a wall thickness of 2.25 m. In the years 1961-63 and 1965 a temple complex with cella and surrounding columned gallery was found within the fort, in the southeast corner.

A possible cult center is also suspected in the area of today's parish church of St. Maximinus. The fort was destroyed at the end of the 4th or the beginning of the 5th century. The sandstone blocks found in the fortifications between 1961 and 1963, measuring up to 2.6 m in length and featuring names in large lettering, were interpreted by the researchers as the seats of a small cult theater from the second half of the 2nd century, belonging to a temple complex.

Outside the Roman Vicus, in the area of today's road between Dillingen and Beckingen, the old B 51, a large Roman complex of a villa with five buildings on Hylborn was excavated based on the discoveries by Philipp Schmitt in the 1970s. The complex was begun in Celtic times in 90 BC and lasted to 234 AD. The largest building has a length of 68 m. The rooms partly enjoyed hypocaust heating and black and white mosaic floors, which are decorated with right- and left-turning swastikas. The luxurious building facilities also included a wooden water pipe, whose hollowed oak trunks were connected with iron sleeves and supplied the system with fresh spring water. By tree-ring dating the water pipe could be dated to the year 163 AD.

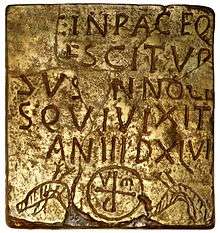

IN PACE QUI ESCIT UR SUS INNOCEN S QUI VIXIT AN III D XLVI

Here rests in peace the innocent Ursus, aged 3 years and 46 days.

The presence of Christians in Pachten is indicated by finds such as the Ursus Stone, the tombstone of a three-year-old boy, discovered in the old church. The special meaning of the stone lies in the Chi Rho monogram XP, which was surrounded by two pigeons carved on the stone, in contrast to the other inscriptions. Such inscriptions are very rare in rural areas, since Christianity developed there later than in urban settlements. The peculiar orientation of the church to south-southwest-north-northeast, in the direction of the old Roman road, and the patronage of Maximin of Trier, who died in 346, indicate that already in late antiquity there was a Christian church in Pachten. When the later Romanesque church was torn down for construction of a Neo-gothic church in 1891 tombs from the Merovingian period were also discovered. These Frankish-Merovingian tombs were fenced with Roman stones. Based on further grave finds in the vicinity of today's church it appears that Pachten in the post-Roman period, lay in ruins only a short time, if at all, and was repopulated by at least the 7th century.

Finds

Systematic investigations in the 20th century have to date uncovered more than 560 graves and the remains of temples, theaters,[5] villas and houses. Most date to the third and fourth centuries AD. A wealth of glass, metal objects, remains of colored wall plaster, heaters, and pottery attest to prosperity. During construction work on the Dillinger Hütte site a grave was found in 2009 documenting the change from Celtic to Roman ways of life.[6] Die in der Pachtener Kirche St. Maximin angebrachte Nachbildung des Grabsteins eines Kindes mit entsprechenden Symbolen belegt die damalige Rolle des Christentums.[7] The replica of the tombstone of a child attached to the church of St. Maximin in Pachten shows symbols of the role of Christianity at that time. One of the 16 towers of the fort was rebuilt in 2009. Many finds are on display in the Museum Pachten.

Further reading

- Glansdorp, Edith: Das Gräberfeld „Margarethenstraße“ in Dillingen-Pachten. Habelt Verlag, Bonn 2005, ISBN 3-7749-3360-X.

- Schmidt, Gertrud: Das römische Pachten, Katalog zu der Ausstellung. Dillingen 1986, OCLC 633277709.

- Lehnert, Aloys: Geschichte der Stadt Dillingen/Saar. Dillingen 1968.

- Alecu, Maria Danliea, Franke, Peter Robert: "Der römische Münzfund von Dillingen-Pachten". In: Bericht der staatlichen Denkmalpflege im Saarland, 16. Saarbrücken 1969.

- Alföldi, Maria: "Die “Fälscherförmchen” von Pachten". In: Germania. Band 52, 1974, S. 426–447.

- Baltzer, Georg: Historische Notizen über die Stadt Saarlouis und deren unmittelbare Umgebung. 1979, ISBN 3-921815-02-9.

- Brunner, H.: "Eine ägyptische Statuette aus Pachten". In: Bericht der staatlichen Denkmalpflege im Saarland, 11. 1964, S. 59–62.

- Kolling, Alfons: "Saravus-Flumen, Römertum im Saarland". In: Die Römer an Mosel und Saar. Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-8053-0767-5, S. 53–67.

- Calmet, Augustin (1748). Histoire de Lorraine (in French). Lorraine: Chez A. Leseure,.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

References

- "Vicus Contiomagus". vici.org. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- Stilwell, William L.; et al. (1976). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- "Vicus Contiomagus, Pachten". Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- Kolling, Alfons (1993). Die Römerstadt in Homburg-Schwarzenacker. Stiftung Römermuseum Homburg-Saarpfalz. ISBN 3-924653-13-5.

- "SR-online, Tour de Kultur 2002]".

- Saarbrücker Zeitung vom 23. Juni 2009

- "Geschichte der Pfarrei St. Maximin". Pfarreiengemeinschaft Dillingen. Retrieved June 22, 2018.