Conatus

In early philosophies of psychology and metaphysics, conatus (/koʊˈneɪtəs/;[1] Latin for "effort; endeavor; impulse, inclination, tendency; undertaking; striving") is an innate inclination of a thing to continue to exist and enhance itself.[2] This "thing" may be mind, matter, or a combination of both. Over the millennia, many different definitions and treatments have been formulated, including seventeenth-century philosophers René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, and Thomas Hobbes who had made significant contributions.[3] The conatus may refer to the instinctive "will to live" of living organisms or to various metaphysical theories of motion and inertia.[4] Often the concept is associated with God's will in a pantheist view of Nature.[3][5] The concept may be broken up into separate definitions for the mind and body and split when discussing centrifugal force and inertia.[6]

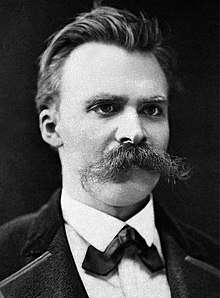

The history of the term conatus is that of a series of subtle tweaks in meaning and clarifications of scope developed over the course of two and a half millennia. Successive philosophers to adopt the term put their own personal twist on the concept, each developing the term differently.[4] The earliest authors to discuss conatus wrote primarily in Latin, basing their usage on ancient Greek concepts. These thinkers therefore used "conatus" not only as a technical term but as a common word and in a general sense. In archaic texts, the more technical usage is difficult to discern from the more common one, and they are also hard to differentiate in translation. In English translations, the term is italicized when used in the technical sense or translated and followed by conatus in brackets.[7] Today, conatus is rarely used in the technical sense, since modern physics uses concepts such as inertia and conservation of momentum that have superseded it. It has, however, been a notable influence on nineteenth- and twentieth-century thinkers such as Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Louis Dumont.

Classical origins

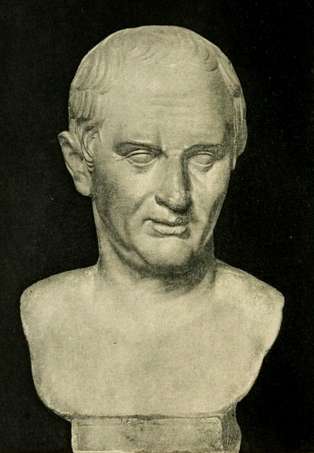

The Latin cōnātus comes from the verb cōnor, which is usually translated into English as, "to endeavor"; but the concept of the conatus was first developed by the Stoics (333–264 BCE) and Peripatetics (c. 335 BCE) before the Common Era. These groups used the word ὁρμή (hormê, translated in Latin by impetus) to describe the movement of the soul towards an object, and from which a physical act results.[8] Classical thinkers, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE) and Diogenes Laërtius (3rd c. CE), expanded this principle to include an aversion to destruction, but continued to limit its application to the motivations of non-human animals. Diogenes Laërtius, for example, specifically denied the application of the term to plants. Before the Renaissance, Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274 CE), Duns Scotus (c. 1266–1308 CE) and Dante Alighieri (1265–1321 CE) expressed similar sentiments using the Latin words vult, velle or appetit as synonyms of conatus; indeed, all four terms may be used to translate the original Greek ὁρμή. Later, Telesius and Campanella extended the ancient Greek notions and applied them to all objects, animate and inanimate.[9]

First Aristotle, then Cicero and Laërtius each alluded to a connection between the conatus and other emotions. In their view, the former induces the latter. They maintained that humans do not wish to do something because they think it "good", but rather they think it "good" because they want to do it. In other words, the cause of human desire is the natural inclination of a body to augment itself in accordance with the principles of the conatus.[10]

Medieval views

There is a traditional connection between conatus and motion itself. Aquinas and Abravanel (1265–1321) both related the concept directly to that which Augustine (354–430 CE) saw to be the "natural movements upward and downward or with their being balanced in an intermediate position" described in his De Civitate Dei, (c. 520 CE). They called this force that causes objects to rise or fall, "amor naturalis", or "natural love".[11]

In the 6th century, John Philoponus (c. 490–c. 570 CE) criticized Aristotle's view of motion, noting the inconsistency between Aristotle's discussion of projectiles, where the medium of aether keeps projectiles going, and his discussion of the void, where there is no such medium and hence a body's motion should be impossible. Philoponus proposed that motion was not maintained by the action of some surrounding medium but by some property, or conatus implanted in the object when it was set in motion. This was not the modern concept of inertia, for there was still the need for an inherent power to keep a body in motion.[12] This view was strongly opposed by Averroës and many scholastic philosophers who supported Aristotle.[13] The Aristotelian view was also challenged in the Islamic world. For example, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) seems to have supported Philoponus' views,[14] while he developed a concept similar to inertia.[15] The concept of inertia was developed more clearly in the work of his contemporary Avicenna, who conceived a permanent force whose effect is dissipated only as a result of external agents such as air resistance, making him "the first to conceive such a permanent type of impressed virtue for non-natural motion."[16] Avicenna's concept of mayl is almost the opposite of the Aristotelian conception of violent motion and is reminiscent of Newton's first law of motion.[17] Avicenna also developed an idea similar to momentum, when he attempted to provide a quantitative relation between the weight and velocity of a moving body.[18]

Jean Buridan (1300–1358) also rejected the notion that this motion-generating property, which he named impetus, dissipated spontaneously. Buridan's position was that a moving object would be arrested by the resistance of the air and the weight of the body which would oppose its impetus. He also maintained that impetus increased with speed; thus, his initial idea of impetus was similar in many ways to the modern concept of momentum. Despite the obvious similarities to more modern ideas of inertia, Buridan saw his theory as only a modification to Aristotle's basic philosophy, maintaining many other peripatetic views, including the belief that there was still a fundamental difference between an object in motion and an object at rest. Buridan also maintained that impetus could be not only linear, but also circular in nature, causing objects such as celestial bodies to move in a circle.[19]

In Descartes

In the first half of the seventeenth century, René Descartes (1596–1650) began to develop a more modern, materialistic concept of the conatus, describing it as "an active power or tendency of bodies to move, expressing the power of God".[20] Whereas the ancients used the term in a strictly anthropomorphic sense similar to voluntary "endeavoring" or "struggling" to achieve certain ends, and medieval Scholastic philosophers developed a notion of conatus as a mysterious intrinsic property of things, Descartes uses the term in a somewhat more mechanistic sense.[21] More specifically, for Descartes, in contrast to Buridan, movement and stasis are two states of the same thing, not different things. Although there is much ambiguity in Descartes' notion of conatus, one can see here the beginnings of a move away from the attribution of desires and intentions to nature and its workings toward a more scientific and modern view.[22]

Descartes rejects the teleological, or purposive, view of the material world that was dominant in the West from the time of Aristotle. The mind is not viewed by Descartes as part of the material world, and hence is not subject to the strictly mechanical laws of nature. Motion and rest, on the other hand, are properties of the interactions of matter according to eternally fixed mechanical laws. God only sets the whole thing in motion at the start, and later does not interfere except to maintain the dynamical regularities of the mechanical behavior of bodies. Hence there is no real teleology in the movements of bodies since the whole thing reduces to the law-governed collisions and their constant reconfigurations. The conatus is just the tendency of bodies to move when they collide with each other. God may set this activity in motion, but thereafter no new motion or rest can be created or destroyed.[23]

Descartes specifies two varieties of the conatus: conatus a centro and conatus recedendi. Conatus a centro, or "tendency towards the center", is used by Descartes as a theory of gravity; conatus recendendi, or "tendency away from the center", represents the centrifugal forces.[6] These tendencies are not to be thought of in terms of animate dispositions and intentions, nor as inherent properties or "forces" of things, but rather as a unifying, external characteristic of the physical universe itself which God has bestowed.[24]

Descartes, in developing his First Law of Nature, also invokes the idea of a conatus se movendi, or "conatus of self-preservation".[25] This law is a generalization of the principle of inertia, which was developed and experimentally demonstrated earlier by Galileo. The principle was formalized by Isaac Newton and made into the first of his three Laws of Motion fifty years after the death of Descartes. Descartes' version states: "Each thing, insofar as in it lies, always perseveres in the same state, and when once moved, always continues to move."[26]

In Hobbes

Conatus and the psyche

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), too, worked off of the previous notions of the conatus principle. However, he criticized the previous definitions for failing to explain the origin of motion. Working toward this end became the primary focus of Hobbes' work in this area. Indeed, Hobbes "reduces all the cognitive functions of the mind to variations of its conative functions".[27]

Furthermore, Hobbes describes emotion as the beginning of motion and the will as the sum of all emotions. This "will" forms the conatus of a body[20] and its physical manifestation is the perceived "will to survive".[3] In order that living beings may thrive, Hobbes says, "they seek peace and fight anything that threatens this peace".[20] Hobbes also equates this conatus with "imagination", and states that a change in the conatus, or will, is the result of "deliberation".[28]

Conatus and physics

I define [conatus] to be motion made in less space and time than can be given; that is, less than can be determined or assigned by exposition or number; that is, motion made through the length of a point, and in an instant or point of time.[29]

As in his psychological theory, Hobbes's physical conatus is an infinitesimal unit of motion. It is the beginning of motion: an inclination in a specified direction. The concept of impetus, as used by Hobbes, is defined in terms of this physical conatus. It is "a measure of the conatus exercised by a moving body over the course of time".[30] Resistance is caused by a contrary conatus; force is this motion plus "the magnitude of the body".[31] Hobbes also uses the word conatus to refer to the "restorative forces" which may cause springs, for example, to contract or expand. Hobbes claims there is some force inherent in these objects that inclines them to return to their previous state. Today, science attributes this phenomenon to material elasticity.[32]

In Spinoza

Conatus is a central theme in the philosophy of Benedict de Spinoza (1632–1677). According to Spinoza, "each thing, as far as it lies in itself, strives to persevere in its being" (Ethics, part 3, prop. 6). Spinoza presents a few reasons for believing this. First, particular things are, as he puts it, modes of God, which means that each one expresses the power of God in a particular way (Ethics, part 3, prop. 6, dem.). Moreover, it could never be part of the definition of God that his modes contradict one another (Ethics, part 3, prop. 5); each thing, therefore, "is opposed to everything which can take its existence away" (Ethics, part 3, prop. 6, dem.). This resistance to destruction is formulated by Spinoza in terms of a striving to continue to exist, and conatus is the word he most often uses to describe this force.[33]

Striving to persevere is not merely something that a thing does in addition to other activities it might happen to undertake. Rather, striving is "nothing but the actual essence of the thing" (Ethics, part 3, prop. 7). Spinoza also uses the term conatus to refer to rudimentary concepts of inertia, as Descartes had earlier.[3] Since a thing cannot be destroyed without the action of external forces, motion and rest, too, exist indefinitely until disturbed.[34]

Behavioral manifestation

The concept of the conatus, as used in Baruch Spinoza's psychology, is derived from sources both ancient and medieval. Spinoza reformulates principles that the Stoics, Cicero, Laërtius, and especially Hobbes and Descartes developed.[35] One significant change he makes to Hobbes' theory is his belief that the conatus ad motum, (conatus to motion), is not mental, but material.[36]

Spinoza, with his determinism, believes that man and nature must be unified under a consistent set of laws; God and nature are one, and there is no free will. Contrary to most philosophers of his time and in accordance with most of those of the present, Spinoza rejects the dualistic assumption that mind, intentionality, ethics, and freedom are to be treated as things separate from the natural world of physical objects and events.[37] His goal is to provide a unified explanation of all these things within a naturalistic framework, and his notion of conatus is central to this project. For example, an action is "free", for Spinoza, only if it arises from the essence and conatus of an entity. There can be no absolute, unconditioned freedom of the will, since all events in the natural world, including human actions and choices, are determined in accord with the natural laws of the universe, which are inescapable. However, an action can still be free in the sense that it is not constrained or otherwise subject to external forces.[38]

Human beings are thus an integral part of nature.[34] Spinoza explains seemingly irregular human behaviour as really "natural" and rational and motivated by this principle of the conatus.[39] In the process, he replaces the notion of free will with the conatus, a principle that can be applied to all of nature and not just man.[34]

Emotions and affects

Spinoza's view of the relationship between the conatus and the human affects is not clear. Firmin DeBrabander, assistant professor of philosophy at the Maryland Institute College of Art, and Antonio Damasio, professor of neuroscience at the University of Southern California, both argue that the human affects arise from the conatus and the perpetual drive toward perfection.[40] Indeed, Spinoza states in his Ethics that happiness, specifically, "consists in the human capacity to preserve itself". This "endeavor" is also characterized by Spinoza as the "foundation of virtue".[41] Conversely, a person is saddened by anything that opposes his conatus.[42]

David Bidney (1908–1987), professor at Yale University, disagrees. Bidney closely associates "desire", a primary affect, with the conatus principle of Spinoza. This view is backed by the Scholium of IIIP9 of the Ethics which states, "Between appetite and desire there is no difference, except that desire is generally related to men insofar as they are conscious of the appetite. So desire can be defined as appetite together with consciousness of the appetite."[3] According to Bidney, this desire is controlled by the other affects, pleasure and pain, and thus the conatus strives towards that which causes joy and avoids that which produces pain.[43]

In Leibniz

Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) was a student of Erhard Weigel (1625–1699) and learned of the conatus principle from him and from Hobbes, though Weigel used the word tendentia (Latin: tendency).[44] Specifically, Leibniz uses the word conatus in his Exposition and Defence of the New System (1695) to describe a notion similar that of Hobbes, but he differentiates between the conatus of the body and soul, the first of which may only travel in a straight line by its own power, and the latter of which may "remember" more complicated motions.[45]

For Leibniz, the problem of motion comes to a resolution of the paradox of Zeno. Since motion is continuous, space must be infinitely divisible. In order for anything to begin moving at all, there must be some mind-like, voluntaristic property or force inherent in the basic constituents of the universe that propels them. This conatus is a sort of instantaneous or "virtual" motion that all things possess, even when they are static. Motion, meanwhile, is just the summation of all the conatuses that a thing has, along with the interactions of things. The conatus is to motion as a point is to space.[46] The problem with this view is that an object that collides with another would not be able to bounce back, if the only force in play were the conatus. Hence, Leibniz was forced to postulate the existence of an aether that kept objects moving and allowed for elastic collisions. Leibniz' concept of a mind-like memory-less property of conatus, coupled with his rejection of atoms, eventually led to his theory of monads.[47]

Leibniz also uses his concept of a conatus in developing the principles of the integral calculus, adapting the meaning of the term, in this case, to signify a mathematical analog of Newton's accelerative "force". By summing an infinity of such conatuses (i.e., what is now called integration), Leibniz could measure the effect of a continuous force.[46] He defines impetus as the result of a continuous summation of the conatus of a body, just as the vis viva (or "living force") is the sum of the inactive vis mortua.[48]

Based on the work of Kepler and probably Descartes, Leibniz develops a model of planetary motion based on the conatus principle, the idea of aether and a fluid vortex. This theory is expounded in the work Tentamen de motuum coelestium causis (1689).[46] According to Leibniz, Kepler's analysis of elliptical orbits into a circular and a radial component can be explained by a "harmonic vortex" for the circular motion combined with a centrifugal force and gravity, both of which are examples of conatus, to account for the radial motion.[47] Leibniz later defines the term monadic conatus, as the "state of change" through which his monads perpetually advance.[49]

Related usages and terms

Several other uses of the term conatus, apart from the primary ones mentioned above, have been formulated by various philosophers over the centuries. There are also some important related terms and concepts which have, more or less, similar meanings and usages. Giambattista Vico (1668–1744) defined conatus as the essence of human society,[50] and also, in a more traditional, hylozoistic sense, as the generating power of movement which pervades all of nature.[51] Nearly a century after the beginnings of modern science, Vico, inspired by Neoplatonism, explicitly rejected the principle of inertia and the laws of motion of the new physics. For him, nature was composed neither of atoms, as in the dominant view, nor of extension, as in Descartes, but of metaphysical points animated by a conatus principle provoked by God.[52]

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) developed a philosophy that contains a principle notably similar to that of Hobbes's conatus. This principle, Wille zum Leben, or "Will to Live", described the specific phenomenon of an organism's self-preservation instinct.[53] Schopenhauer qualified this, however, by suggesting that the Will to Live is not limited in duration. Rather, "the will wills absolutely and for all time", across generations.[54] Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), an early disciple of Schopenhauer, developed a separate principle which comes out of a rejection of the primacy of Schopenhauer's Will to Live and other notions of self-preservation. He called his version the Will to Power, or Wille zur Macht.[55]

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), greatly depended on Spinoza's formulation of the conatus principle as a system of self-preservation, though he never cited him directly in any of his published works.[56][57] Around the same time, Henri Bergson (1859–1941), developed the principle of the élan vital, or "vital impulse", which was thought to aid in the evolution of organisms. This concept, which implies a fundamental driving force behind all life, is reminiscent of the conatus principle of Spinoza and others.[58]

For Max Scheler, the concept of Drang is the centerpiece of philosophical anthropology and metaphysics. Though his concept has been important throughout his entire philosophical career, it was only developed later in his life when his focus shifted from phenomenology to metaphysics. Like Bergson's élan vital, Drang (drive or impulsion) is the impetus of all life; however, unlike in Bergson's vitalistic metaphysics, the significance of Drang is that it provides the motivation and driving force even of Spirit (Geist). Spirit, which includes all theoretical intentionality, is powerless without the movement of Drang, the material principle, as well as Eros, the psychological principle.[59]

The cultural anthropologist Louis Dumont (1911–1988), described a cultural conatus built directly upon Spinoza's seminal definition in IIIP3 of his Ethics. The principle behind this derivative concept states that any given culture, "tends to persevere in its being, whether by dominating other cultures or by struggling against their domination".[60]

Modern significance

Physical

After the advent of Newtonian physics, the concept of a conatus of all physical bodies was largely superseded by the principle of inertia and conservation of momentum. As Bidney states, "It is true that logically desire or the conatus is merely a principle of inertia ... the fact remains, however, that this is not Spinoza's usage."[61] Likewise, conatus was used by many philosophers to describe other concepts which have slowly been made obsolete. Conatus recendendi, for instance, became the centrifugal force, and gravity is used where conatus a centro had been previously.[6] Today, the topics with which conatus dealt are matters of science and are thus subject to inquiry by the scientific method.[62]

Biological

The archaic concept of conatus is today being reconciled with modern biology by scientists such as Antonio Damasio. The conatus of today, however, is explained in terms of chemistry and neurology where, before, it was a matter of metaphysics and theurgy.[63] This concept may be "constructed so as to maintain the coherence of a living organism's structures and functions against numerous life-threatening odds".[64]

Systems theory

The Spinozistic conception of a conatus was a historical precursor to modern theories of autopoiesis in biological systems.[65] In systems theory and the sciences in general, the concept of a conatus may be related to the phenomenon of emergence, whereby complex systems may spontaneously form from multiple simpler structures. The self-regulating and self-maintaining properties of biological and even social systems may thus be considered modern versions of Spinoza's conatus principle;[66] however, the scope of the idea is definitely narrower today without the religious implications of the earlier variety.[67]

See also

Notes

- "conatus — Definitions from Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. Lexico Publishing Group. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- Traupman 1966, p. 52

- LeBuffe 2006

- Wolfson 1934, p. 202

- Schopenhauer 1958, p. 357

- Kollerstrom 1999, pp. 331–356

- Leibniz 1989, p. 118

- Clement of Alexandria, in SVF, III, 377; Cicero, De Officiis, I, 132; Seneca the Younger, Epistulae morales ad Lucilium, 113, 23

- Wolfson 1934, pp. 196,199,202

- Wolfson 1934, p. 204

- Wolfson 1934, pp. 197,200

- Sorabji 1988, pp. 227,228

- Leaman 1997

- Sabra 1994, pp. 133–136

- Salam 1987, pp. 179–213

- Sayili 1987, p. 477:

"It was a permanent force whose effect got dissipated only as a result of external agents such as air resistance. He is apparently the first to conceive such a permanent type of impressed virtue for non-natural motion."

- Sayili 1987, p. 477:

"Indeed, self-motion of the type conceived by Ibn Sina is almost the opposite of the Aristotelian conception of violent motion of the projectile type, and it is rather reminiscent of the principle of inertia, i.e., Newton's first law of motion."

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr & Mehdi Amin Razavi (1996), The Islamic intellectual tradition in Persia, Routledge, p. 72, ISBN 978-0-7007-0314-2

- Grant 1964, pp. 265–292

- Pietarinen 2000

- Garber 1992, pp. 150,154

- Gaukroger 1980, pp. 178–179

- Gueroult 1980, pp. 120–34

- Garber 1992, pp. 180,184

- Wolfson 1934, p. 201

- Blackwell 1966, p. 220

- Bidney 1962, p. 91

- Schmitter 2006

- Hobbes 1998, III, xiv, 2

- Jesseph 2006, p. 22

- Jesseph 2006, p. 35

- Osler 2001, pp. 157–61

- Allison 1975, p. 124

- Allison 1975, p. 125

- Morgan 2006, p. ix

- Bidney 1962, p. 93

- Jarrett 1991, pp. 470–475

- Lachterman 1978

- Dutton 2006, chp. 5

- DeBrabander 2007, pp. 20–1

- Damasio 2003, p. 170

- Damasio 2003, pp. 138–9

- Bidney 1962, p. 87

- Arthur 1998

- Leibniz 1988, p. 135

- Gillespie 1971, pp. 159–161

- Carlin 2004, pp. 365–379

- Duchesneau 1998, pp. 88–89

- Arthur 1994, sec. 3

- Goulding 2005, p. 22040

- Vico 1710, pp. 180–186

- Landucci 2004, pp. 1174,1175

- Rabenort 1911, p. 16

- Schopenhauer 1958, p. 568

- Durant & Durant 1963, chp. IX

- Damasio 2003, p. 260

- Bidney 1962, p. 398

- Schrift 2006, p. 13

- Scheler 2008, pp. 231–41, 323–33

- Polt 1996

- Bidney 1962, p. 88

- Bidney 1962

- Damasio 2003, p. 37

- Damasio 2003, p. 36

- Ziemke 2007, p. 6

- Sandywell 1996, pp. 144–5

- Mathews 1991, p. 110

References

- Allison, Henry E. (1975), Benedict de Spinoza, San Diego: Twayne Publishers, ISBN 978-0-8057-2853-8

- Arthur, Richard (1994), "Space and relativity in Newton and Leibniz", The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 45 (1): 219–240, doi:10.1093/bjps/45.1.219, Thomson Gale Document Number:A16109468

- Arthur, Richard (1998), "Cohesion, Division and Harmony: Physical Aspects of Leibniz's Continuum Problem (1671–1686)", Perspectives on Science, 6 (1): 110–135, Thomson Gale Document Number:A54601187

- Bidney, David (1962), The Psychology and Ethics of Spinoza: A Study in the History and Logic of Ideas, New York: Russell & Russell

- Blackwell, Richard J. (1966), "Descartes' Laws of Motion", Isis, 57 (2): 220–234, doi:10.1086/350115

- Carlin, Lawrence (2004), "Leibniz on Conatus, Causation, and Freedom", Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 85 (4): 365–379, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0114.2004.00205.x

- Damasio, Antonio R. (2003), Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling, Florida: Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-15-100557-4

- DeBrabander, Firmin (March 15, 2007), Spinoza and the Stoics: Power, Politics and the Passions, London; New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8264-9393-4

- Duchesneau, Francois (Spring–Summer 1998), "Leibniz's Theoretical Shift in the Phoranomus and Dynamica de Potentia", Perspectives on Science, 6 (2): 77–109, Thomson Gale Document Number: A54601186

- Duff, Robert Alexander (1903), Spinoza's Political and Ethical Philosophy, J. Maclehose and Sons, retrieved 2007-03-19

- Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (1963), "XXII: Spinoza: 1632–77", The Story of Civilization, 8, New York: Simon & Schuster, archived from the original on 2007-04-23, retrieved 2007-03-29

- Dutton, Blake D. (2006), "Benedict De Spinoza", The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, retrieved 2007-01-15

- Garber, Daniel (1992), Descartes' Metaphysical Physics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-28217-6

- Gaukroger, Stephen (1980), Descartes: Philosophy, Mathematics and Physics, Sussex: Harvester Press., ISBN 978-0-389-20084-0

- Gillespie, Charles S. (1971), "Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm", Dictionary of Scientific Biography, New York, retrieved 2007-03-27

- Goulding, Jay (2005), Horowitz, Maryanne (ed.), "Society", New Dictionary of the History of Ideas, Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 5, Thomson Gale Document Number:CX3424300736

- Grant, Edward (1964), "Motion in the Void and the Principle of Inertia in the Middle Ages", Isis, 55 (3): 265–292, doi:10.1086/349862

- Gueroult, Martial (1980), "The Metaphysics and Physics of Force in Descartes", in Stephen Gaukroger (ed.), Descartes: Philosophy, Mathematics and Physics, Sussex: Harvester Press

- Hobbes, Thomas (1998), De Corpore, New York: Oxford Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-19-283682-3

- Jarrett, Charles (1991), "Spinoza's Denial of Mind-Body Interaction and the Explanation of Human Action", The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 29 (4): 465–486, doi:10.1111/j.2041-6962.1991.tb00604.x

- Jesseph, Doug (2006), "Hobbesian Mechanics" (PDF), Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy, 3, ISBN 978-0-19-920394-9, archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-07, retrieved 2007-03-10

- Kollerstrom, Nicholas (1999), "The Path of Halley's Comet, and Newton's Late Apprehension of the Law of Gravity", Annals of Science, 59 (4): 331–356, doi:10.1080/000337999296328

- Lachterman, D. (1978), Robert Shahan; J.I. Biro. (eds.), The Physics of Spinoza's Ethics in Spinoza: New Perspectives, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press

- Landucci, Sergio (2004), "Vico, Giambattista", in Gianni Vattimo (ed.), Enciclopedia Garzantine della Filosofia, Milan: Garzanti Editore, ISBN 978-88-11-50515-0

- Leaman, Olivier (1997), Averroes and his philosophy, Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, ISBN 978-0-7007-0675-4

- LeBuffe, Michael (2006-03-20), "Spinoza's Psychological Theory", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), retrieved 2007-01-15

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm, Freiherr von (December 31, 1988) [1695], "Exposition and Defence of the New System", in Morris, Mary, M.A. (ed.), Leibniz: Philosophical Writings, J.M. Dent & Sons, p. 136, ISBN 978-0-460-87045-0

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm, Freiherr von (1989) [1695], Ariew, Roger; Garber, Daniel (eds.), Philosophical essays, Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co., ISBN 978-0-87220-063-0

- Lin, Martin (2004), "Spinoza's Metaphysics of Desire: IIIP6D", Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie, 86 (1): 21–55, doi:10.1515/agph.2004.003

- Mathews, Freya (1991), The Ecological Self, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-10797-6

- Morgan, Michael L. (2006), The Essential Spinoza, Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., p. ix, ISBN 978-0-87220-803-2

- Osler, Margaret J. (2001), "Whose ends? Teleology in early modern natural philosophy", Osiris, 16 (1): 151–168, doi:10.1086/649343, Thomson Gale Document Number:A80401149

- Pietarinen, Juhani (2000-08-08), "Hobbes, Conatus and the Prisoner's Dilemma", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Boston University, retrieved 2007-01-15

- Polt, Richard (1996), "German Ideology: From France to Germany and Back", The Review of Metaphysics, 49 (3), Thomson Gale Document Number:A18262679

- Rabenort, William Louis (1911), Spinoza as Educator, New York City: Teachers College, Columbia University

- Sabra, A. I. (1994), The astronomical origin of Ibn al-Haytham's concept of experiment, Paris: Aldershot Variorum, ISBN 978-0-86078-435-7

- Salam, Abdus (1987) [1984], Lai, C. H. (ed.), Ideals and Realities: Selected Essays of Abdus Salam, Singapore: World Scientific

- Sandywell, Barry (1996), Reflexivity and the Crisis of Western Reason, 1: Logological Investigations, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 144–5, ISBN 978-0-415-08756-8

- Sayili, A. (1987), "Ibn Sīnā and Buridan on the Motion of the Projectile", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 500 (1): 477–482, Bibcode:1987NYASA.500..477S, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37219.x

- Scheler, Max (2008), The Constitution of the Human Being, John Cutting, Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, p. 430

- Schmitter, Amy M. (2006), "Hobbes on the Emotions", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, retrieved 2006-03-04

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1958), Payne, E.F.J. (ed.), The World as Will and Representation, 1, Clinton, Massachusetts: The Colonial Press Inc.

- Schrift, Alan D. (2006), Twentieth-Century French Philosophy: Key Themes and Thinkers, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-3218-3

- Sorabji, Richard (1988), Matter, Space, and Motion: Theories in Antiquity and their Sequel, London: Duckworth

- Spinoza, Baruch (2005), Curley, Edwin (ed.), Ethics, New York: Penguin Classics, pp. 144–146, ISBN 978-0-14-043571-9

- Traupman, John C. (1966), The New Collegiate Latin & English Dictionary, New York: Bantam Books, ISBN 978-0-553-25329-0

- Vico, Giambattista (1710), L.M. Palmer (ed.), De antiquissima Italiorum sapientia ex linguae originibus eruenda librir tres, Ithaca: Cornell University Press

- Wolfson, Harry Austryn (1934), The Philosophy of Spinoza, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-66595-8

- Ziemke, Tom (2007), Chella, A.; Manzotti, R. (eds.), "What's life got to do with it?", Artificial Consciousness, Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic, retrieved 2007-05-27

Further reading

- Ariew, Roger (2003), Historical dictionary of Descartes and Cartesian philosophy, Lanham, Md. ; Oxford: Scarecrow Press

- Bernstein, Howard R. (1980), "Conatus, Hobbes, and the Young Leibniz", Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 11 (1): 167–81, doi:10.1016/0039-3681(80)90003-5

- Bove, Laurent (1992), L'affirmation absolue d'une existence essai sur la stratégie du conatus Spinoziste, Université de Lille III: Lille, OCLC 57584015

- Caird, Edward (1892), Essays on Literature and Philosophy: Glasgow, J. Maclehose and sons, retrieved 2007-03-20

- Carlin, Laurence (December 2004), "Leibniz on Conatus, causation and freedom", Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 85 (4): 365–79, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0114.2004.00205.x

- Chamberland, Jacques (September 2000), Duchesneau, Francois (ed.), "Les conatus chez Thomas Hobbes", The Review of Metaphysics, Université de Montreal, 54 (1)

- Deleuze, Gilles (1988), Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, City Lights Book

- Garber, Daniel (1994), "Descartes and Spinoza on Persistence and Conatus", Studia Spinozana, Walther & Walther, 10

- Garret, D. (2002), Koistinen, Olli; Biro, John (eds.), "Spinoza's Conatus Argument", Spinoza: Metaphysical Themes, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1: 127–152, doi:10.1093/019512815X.003.0008, ISBN 9780195128154

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm; Gerhardt, K.; Langley, Alfred Gideon (1896), Langley, Alfred Gideon (ed.), New Essays Concerning Human Understanding, Macmillan & Co., ltd., retrieved 2007-03-19

- Lyon, Georges (1893), La philosophie de Hobbes, F. Alean, retrieved 2007-03-19

- Montag, Warren (1999), Bodies, Masses, Power: Spinoza and his Contemporaries, New York: Verso, ISBN 978-1-85984-701-5

- Rabouin, David (June–July 2000), "Entre Deleuze et Foucault : Le jeu du désir et du pouvoir", Critique: 637–638

- Schrijvers, M. (1999), Yovel, Yirmiyahu (ed.), "The Conatus and the Mutual Relationship Between Active and Passive Affects in Spinoza", Desire and Affect: Spinoza as Psychologist, New York: Little Room Press

- Schulz, O. (1995), "Schopenhauer's Ethik — die Konzequenz aus Spinoza's Metaphysik?", Schopenhauer-Jahrbuch, 76: 133–149, ISSN 0080-6935

- Steinberg, Diane (Spring 2005), "Belief, Affirmation, and the Doctrine of Conatus in Spinoza", Southern Journal of Philosophy, 43 (1): 147–158, doi:10.1111/j.2041-6962.2005.tb01948.x, ISSN 0038-4283

- Tuusvuori, Jarkko S. (March 2000), Nietzsche & Nihilism: Exploring a Revolutionary Conception of Philosophical Conceptuality, University of Helsinki, ISBN 978-951-45-9135-8

- Wendell, Rich (1997), Spinoza's Conatus doctrine: existence, being, and suicide, Waltham, Mass., OCLC 37542442

- Youpa, A. (2003), "Spinozistic Self-Preservation", The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 41 (3): 477–490, doi:10.1111/j.2041-6962.2003.tb00962.x

.jpg)