Competition (companies)

Company competition, or competitiveness, pertains to the ability and performance of a firm, sub-sector or country to sell and supply goods and services in a given market, in relation to the ability and performance of other firms, sub-sectors or countries in the same market. It involves one company trying to figure out how to take away market share from another company.

Firm competition

Empirical observation confirms that resources (capital, labor, technology) and talent tend to concentrate geographically (Easterly and Levine 2002). This result reflects the fact that firms are embedded in inter-firm relationships with networks of suppliers, buyers and even competitors that help them to gain competitive advantages in the sale of its products and services. While arms-length market relationships do provide these benefits, at times there are externalities that arise from linkages among firms in a geographic area or in a specific industry (textiles, leather goods, silicon chips) that cannot be captured or fostered by markets alone. The process of "clusterization", the creation of "value chains", or "industrial districts" are models that highlight the advantages of networks.

Within capitalist economic systems, the drive of enterprises is to maintain and improve their own competitiveness, this practically pertains to business sectors.

National competition

Economic competition is a political-economic concept that emerged in trade and policy discussions in the last decades of the 20th century. Competition theory posits that while protectionist measures may provide short-term remedies to economic problems caused by imports, firms and nations must adapt their production processes in the long term to produce the best products at the lowest price. In this way, even without protectionism, their manufactured goods are able to compete successfully against foreign products both in domestic markets and in foreign markets. Competition emphasizes the use of comparative advantage to decrease trade deficits by exporting larger quantities of goods that a particular nation excels at producing, while simultaneously importing minimal amounts of goods that are relatively difficult or expensive to manufacture. Trade Policy can be used to establish unilaterally and multilaterally negotiated rule of law agreements protecting fair and open global markets. While trade policy is important to the economic success of nations, competitiveness embodies the need to address all aspects affecting the production of goods that will be successful in the global market, including but not limited to managerial decision making, labor, capital, and transportation costs, reinvestment decisions, the acquisition and availability of human capital, export promotion and financing, and increasing labor productivity.

Competition results from a comprehensive policy that both maintains a favorable global trading environment for producers and domestically encourages firms to work for lower production costs while increasing the quality of output so that they are able to capitalize on favorable trading environments.[1] These incentives include export promotion efforts and export financing—including financing programs that allow small and medium-sized companies to finance the capital costs of exporting goods.[2] In addition, trading on the global scale increases the robustness of American industry by preparing firms to deal with unexpected changes in the domestic and global economic environments, as well as changes within the industry caused by accelerated technological advancements According to economist Michael Porter, "A nation's competitiveness depends on the capacity of its industry to innovate and upgrade."[3]

History of competition

Advocates for policies that focus on increasing competition argue that enacting only protectionist measures can cause atrophy of domestic industry by insulating them from global forces. They further argue that protectionism is often a temporary fix to larger, underlying problems: the declining efficiency and quality of domestic manufacturing. American competition advocacy began to gain significant traction in Washington policy debates in the late 1970s and early 1980s as a result of increasing pressure on the United States Congress to introduce and pass legislation increasing tariffs and quotas in several large import-sensitive industries. High level trade officials, including commissioners at the U.S. International Trade Commission, pointed out the gaps in legislative and legal mechanisms in place to resolve issues of import competition and relief. They advocated policies for the adjustment of American industries and workers impacted by globalization and not simple reliance on protection.[4]

1980s

As global trade expanded after the 1979-1982 recession, some American industries, such as the steel and automobile sectors, which had long thrived in a large domestic market, were increasingly exposed to foreign competition. Specialization, lower wages, and lower energy costs allowed developing nations entering the global market to export high quantities of low cost goods to the United States. Simultaneously, domestic anti-inflationary measures (e.g. higher interest rates set by the Federal Reserve) led to a 65% increase in the exchange value of the US dollar in the early 1980s. The stronger dollar acted in effect as an equal percent tax on American exports and equal percent subsidy on foreign imports.[5] American producers, particularly manufacturers, struggled to compete both overseas and in the US marketplace, prompting calls for new legislation to protect domestic industries.[6] In addition, the recession of 1979-82 did not exhibit the traits of a typical recessionary cycle of imports, where imports temporarily decline during a downturn and return to normal during recovery. Due to the high dollar exchange rate, importers still found a favorable market in the United States despite the recession. As a result, imports continued to increase in the recessionary period and further increased in the recovery period, leading to an all-time high trade deficit and import penetration rate. The high dollar exchange rate in combination with high interest rates also created an influx of foreign capital flows to the United States and decreased investment opportunities for American businesses and individuals.[5]

The manufacturing sector was most heavily impacted by the high dollar value. In 1984, the manufacturing sector faced import penetration rates of 25%.[7] The "super dollar" resulted in unusually high imports of manufactured goods at suppressed prices. The U.S. steel industry faced a combination of challenges from increasing technology, a sudden collapse of markets due to high interest rates, the displacement of large integrated producers, increasingly uncompetitive cost structure due to increasing wages and reliance on expensive raw materials, and increasing government regulations around environmental costs and taxes. Added to these pressures was the import injury inflicted by low cost, sometimes more efficient foreign producers, whose prices were further suppressed in the American market by the high dollar.

The 1984 Trade Act developed new provisions for adjustment assistance, or assistance for industries that are damaged by a combination of imports and a changing industry environment. It maintained that as a requirement for receiving relief, the steel industry would be required to implement measures to overcome other factors and adjust to a changing market.[8] The act built on the provisions of the Trade Act of 1974 and worked to expand, rather than limit, world trade as a means to improve the American economy. Not only did this act give the President greater authority in giving protections to the steel industry, it also granted the President the authority to liberalize trade with developing economies through Free Trade Agreements (FTA's) while extending the Generalized System of Preferences. The Act also made significant updates to the remedies and processes for settling domestic trade disputes.[9]

The injury caused by imports strengthened by the high dollar value resulted in job loss in the manufacturing sector, lower living standards, which put pressure on Congress and the Reagan Administration to implement protectionist measures. At the same time, these conditions catalyzed a broader debate around the measures necessary to develop domestic resources and to advance US competition. These measures include increasing investment in innovative technology, development of human capital through worker education and training, and reducing costs of energy and other production inputs. Competitiveness is an effort to examine all the forces needed to build up the strength of a nation's industries to compete with imports.[10]

In 1988, the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act was passed. The Act's underlying goal was to bolster America's ability to compete in the world marketplace. It incorporated language on the need to address sources of American competition and to add new provisions for imposing import protection. The Act took into account U.S. import and export policy and proposed to provide industries more effective import relief and new tools to pry open foreign markets for American business.[11] Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 had provided for investigations into industries that had been substantially damaged by imports. These investigations, conducted by the USITC, resulted in a series of recommendations to the President to implement protection for each industry. Protection was only offered to industries where it was found that imports were the most important cause of injury over other sources of injury.[12]

Section 301 of the 1988 Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act contained provisions for the United States to ensure fair trade by responding to violations of trade agreements and unreasonable or unjustifiable trade-hindering activities by foreign governments. A sub-provision of Section 301 focused on ensuring intellectual property rights by identifying countries that deny protection and enforcement of these rights, and subjecting them to investigations under the broader Section 301 provisions.[13] Expanding U.S. access to foreign markets and shielding domestic markets reflected an increased interest in the broader concept of competition for American producers.[14] The Omnibus amendment, originally introduced by Rep. Dick Gephardt, was signed into effect by President Reagan in 1988 and renewed by President Bill Clinton in 1994 and 1999.[15]

1990s

While competition policy began to gain traction in the 1980s, in the 1990s it became a concrete consideration in policy making, culminating in President Clinton's economic and trade agendas. The Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Policy expired in 1991; Clinton renewed it in 1994, representing a renewal of focus on a competitiveness-based trade policy.

According to the Competitiveness Policy Council Sub-council on Trade Policy, published in 1993, the main recommendation for the incoming Clinton Administration was to make all aspects of competition a national priority. This recommendation involved many objectives, including using trade policy to create open and fair global markets for US exporters through free trade agreements and macroeconomic policy coordination, creating and executing a comprehensive domestic growth strategy between government agencies, promoting an "export mentality", removing export disincentives, and undertaking export financing and promotion efforts.

The Trade Sub-council also made recommendations to incorporate competition policy into trade policy for maximum effectiveness, stating "trade policy alone cannot ensure US competitiveness". Rather, the Subcouncil asserted trade policy must be part of an overall strategy demonstrating a commitment at all policy levels to guarantee our future economic prosperity.[1] The Sub-council argued that even if there were open markets and domestic incentives to export, US producers would still not succeed if their goods could not compete against foreign products both globally and domestically.

In 1994, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) became the World Trade Organization (WTO), formally creating a platform to settle unfair trade practice disputes and a global judiciary system to address violations and enforce trade agreements. Creation of the WTO strengthened the international dispute settlement system that had operated in the preceding multilateral GATT mechanism. That year, 1994, also saw the installment of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which opened markets across the United States, Canada, and Mexico.[16]

In recent years, the concept of competition has emerged as a new paradigm in economic development. Competition captures the awareness of both the limitations and challenges posed by global competition, at a time when effective government action is constrained by budgetary constraints and the private sector faces significant barriers to competing in domestic and international markets. The Global Competitiveness Report of the World Economic Forum defines competitiveness as "the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country".[17]

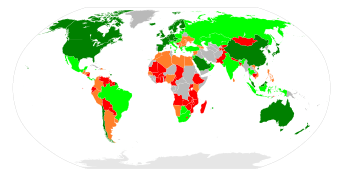

The term is also used to refer in a broader sense to the economic competition of countries, regions or cities. Recently, countries are increasingly looking at their competition on global markets. Ireland (1997), Saudi Arabia (2000), Greece (2003), Croatia (2004), Bahrain (2005), the Philippines (2006), Guyana, the Dominican Republic and Spain (2011) [18] are just some examples of countries that have advisory bodies or special government agencies that tackle competition issues. Even regions or cities, such as Dubai or the Basque Country(Spain), are considering the establishment of such a body.

The institutional model applied in the case of National Competitiveness Programs (NCP) varies from country to country, however, there are some common features. The leadership structure of NCPs relies on strong support from the highest level of political authority. High-level support provides credibility with the appropriate actors in the private sector. Usually, the council or governing body will have a designated public sector leader (president, vice-president or minister) and a co-president drawn from the private sector. Notwithstanding the public sector's role in strategy formulation, oversight, and implementation, national competition programs should have strong, dynamic leadership from the private sector at all levels – national, local and firm. From the outset, the program must provide a clear diagnostic of the problems facing the economy and a compelling vision that appeals to a broad set of actors who are willing to seek change and implement an outward-oriented growth strategy. Finally, most programs share a common view on the importance of networks of firms or "clusters" as an organizing principal for collective action. Based on a bottom-up approach, programs that support the association among private business leadership, civil society organizations, public institutions and political leadership can better identify barriers to competition develop joint-decisions on strategic policies and investments; and yield better results in implementation.

National competition is said to be particularly important for small open economies, which rely on trade, and typically foreign direct investment, to provide the scale necessary for productivity increases to drive increases in living standards. The Irish National Competitiveness Council uses a Competitiveness Pyramid structure to simplify the factors that affect national competition. It distinguishes in particular between policy inputs in relation to the business environment, the physical infrastructure and the knowledge infrastructure and the essential conditions of competitiveness that good policy inputs create, including business performance metrics, productivity, labour supply and prices/costs for business.

Competition is important for any economy that must rely on international trade to balance import of energy and raw materials. The European Union (EU) has enshrined industrial research and technological development (R&D) in her Treaty in order to become more competitive. In 2009, €12 billion of the EU budget [19] (totalling €133.8 billion) will go on projects to boost Europe's competition. The way for the EU to face competition is to invest in education, research, innovation and technological infrastructures.[20][21]

The International Economic Development Council (IEDC) [22] in Washington, D.C. published the "Innovation Agenda: A Policy Statement on American Competitiveness". This paper summarizes the ideas expressed at the 2007 IEDC Federal Forum and provides policy recommendations for both economic developers and federal policy makers that aim to ensure America remains globally competitive in light of current domestic and international challenges.[23]

International comparisons of national competition are conducted by the World Economic Forum, in its Global Competitiveness Report, and the Institute for Management Development,[24] in its World Competitiveness Yearbook.[25]

Scholarly analyses of national competition have largely been qualitatively descriptive.[26] Systematic efforts by academics to define meaningfully and to quantitatively analyze national competitiveness have been made,[27] with the determinants of national competitiveness econometrically modeled.[28]

A US government sponsored program under the Reagan administration called Project Socrates, was initiated to, 1) determine why US competition was declining, 2) create a solution to restore US competition. The Socrates Team headed by Michael Sekora, a physicist, built an all-source intelligence system to research all competition of mankind from the beginning of time. The research resulted in ten findings which served as the framework for the "Socrates Competitive Strategy System". Among the ten finding on competition was that 'the source of all competitive advantage is the ability to access and utilize technology to satisfy one or more customer needs better than competitors, where technology is defined as any use of science to achieve a function".[29]

Role of infrastructure investments

Some development economists believe that a sizeable part of Western Europe has now fallen behind the most dynamic amongst Asia's emerging nations, notably because the latter adopted policies more propitious to long-term investments: "Successful countries such as Singapore, Indonesia and South Korea still remember the harsh adjustment mechanisms imposed abruptly upon them by the IMF and World Bank during the 1997–1998 'Asian Crisis' […] What they have achieved in the past 10 years is all the more remarkable: they have quietly abandoned the "Washington consensus" [the dominant Neoclassical perspective] by investing massively in infrastructure projects […] this pragmatic approach proved to be very successful."[30]

The relative advancement of a nation's transportation infrastructure can be measured using indices such as the (Modified) Rail Transportation Infrastructure Index (M-RTI or simply 'RTI') combining cost-efficiency and average speed metrics [31]

Trade competition

While competition is understood at a macro-scale, as a measure of a country's advantage or disadvantage in selling its products in international markets. Trade competition can be defined as the ability of a firm, industry, city, state or country, to export more in value added terms than it imports.

Using a simple concept to measure heights that firms can climb may help improve execution of strategies. International competition can be measured on several criteria but few are as flexible and versatile to be applied across levels as Trade Competitiveness Index (TCI).[32]

Trade Competitiveness Index (TCI)

TCI can be formulated as ratio of forex (FX) balance to total forex as given in equation below. It can be used as a proxy to determine health of foreign trade, .The ratio from -1 to 1; higher ratio being indicative of higher international trade competitiveness.

In order to identify exceptional firms, trends in TCI can be assessed longitudinally for each company and country. The simple concept of trade competitiveness index (TCI) can be a powerful tool for setting targets, detecting patterns and can also help with diagnosing causes across levels. Used judiciously in conjunction with the volume of exports, TCI can give quick views of trends, benchmarks and potential. Though there is found to be a positive correlation between the profits and forex earnings, we cannot blindly conclude the increase in the profits is due to the increase in the forex earnings. The TCI is an effective criteria, but need to be complemented with other criteria to have better inferences.

Criticism

Krugman (1994) points to the ways in which calls for greater national competition frequently mask intellectual confusion arguing that, in the context of countries, productivity is what matters and "the world's leading nations are not, to any important degree, in economic competition with each other." Krugman warns that thinking in terms of competition could lead to wasteful spending, protectionism, trade wars, and bad policy.[33] As Krugman puts it in his crisp, aggressive style "So if you hear someone say something along the lines of 'America needs higher productivity so that it can compete in today's global economy', never mind who he is, or how plausible he sounds. He might as well be wearing a flashing neon sign that reads: 'I don't know what I'm talking about'."

If the concept of national competition has any substantive meaning it must reside in the factors about a nation that facilitates productivity and alongside criticism of nebulous and erroneous conceptions of national competition systematic and rigorous attempts like Thompson's [27] need to be elaborated.

See also

References

- Trade Policy Subcouncil, "A Trade Policy for a More Competitive America: Report of the Trade Policy Subcouncil to the Competitiveness Policy Council." (1993), 171

- Trade Policy Subcouncil, "A Trade Policy for a More Competitive America: Report of the Trade Policy Subcouncil to the Competitiveness Policy Council." (1993), 180-183

- Porter, Michael E. "The Competitive Advantage of Nations." Harvard Business Review. (1990)

- Stern, Paula. "The Long and the Short of US International Trade: The Crisis Deepens Despite Recovery." 12 Oct 1984, The Business Council, Homestead, VA.

- Paula Stern, "A Realistic Approach of American International Trade Opportunities," The International Trade Seminar, 14 September 1984, Memphis, TN; Paula Stern, "The Long and the Short of US International Trade: The Crisis Deepens Despite Recovery," October 12, 1984, The Business Council, Homestead, VA.

- Paula Stern, "Macro Policy, Economic Health, and the International Order: The Crisis Deepens Despite Recovery," December 17, 1984, Group of Thirty, New York, New York.

- Stern, Paula. "Macro Policy, Economic Health, and the International Order: The Crisis Deepens Despite Recovery."17 Dec 1984, Group of Thirty, New York, New York.

- Stern, Paula. "Additional Views of Chairwoman Paula Stern on Steel." Jul 1984

- Washington Trade Report, "Dictionary of Trade Policy."

- Paula Stern, "Economic Policy and the US Trade Crisis: Towards a National Trade Policy," April 19, 1985, Washington, DC.

- Paula Stern, "Level Playing Field or Mine Field," Across the Board, Oct. 1988.

- Stern, Paula. "A Realistic Approach of American International Trade Opportunities." The International Trade Seminar, 14 Sept 1984, Memphis, TN.

- Fennel, Bill and Alan Dunn, "Memorandum on Brief Comparison of Section 301 and Special Section 301 Trade Laws"Stewart and Stewart, 23 April 2004

- Paula Stern, "Stop the Trade Bill Hysteria," The New York Times, 15 Dec. 1987.

- Appleyard, op. cit; Cass, op. cit.

- Brainard, Lael. "Trade Policy in the 1990s." Brookings Institution. 29 Jun. 2001.

- World Economic Forum, The Global Competitiveness Report 2009–2010, p. 3

- "El "think tank" para la competitividad de la economía quiere "devolver la confianza a España"". Diariosigloxxi.com. Archived from the original on 2013-08-01. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- EU Budget 2009: gearing up for economic recovery

- Muldur, U., et al., "A New Deal for an Effective European Research Policy," Springer 2006 ISBN 978-1-4020-5550-8

- Stajano, A. "Research, Quality, Competitiveness. EU Technology Policy for the Knowledge-based Society," Springer 2009 ISBN 978-0-387-79264-4

- "International Economic Development Council". Iedconline.org. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- Archived November 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "IMD business school, Switzerland". Imd.ch. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- "WCC – Home". Imd.ch. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- Porter M E, 1990, The Competitive Advantage of Nations London: Macmillan

- Thompson, E R, 2003. A grounded approach to identifying national competitive advantage, Environment and Planning A, 35, 631–657.

- Thompson, E. R. 2004. National competitiveness: A question of cost conditions or institutional circumstances? British Journal of Management, 15(3): 197–218.

- Smith, Esther (May 1988). "DoD Unveils Competitive Tool: Project Socrates Offers Valuable Analysis". Washington Technology.

- M. Nicolas J. Firzli quoted by Andrew Mortimer (May 14, 2012). "Country Risk: Asia Trading Places with the West". Euromoney Country Risk. . Retrieved 5 Nov 2012.

- M. Nicolas J. Firzli : '2014 LTI Rome Conference: Infrastructure-Driven Development to Conjure Away the EU Malaise?', Revue Analyse Financière, Q1 2015 – Issue N°54

- Manthri P.; Bhokray K. & Momaya K. S. (2015). "Export Competitiveness of Select Firms from India: Glimpse of Trends and Implications" (PDF). Indian Journal of Marketing. 45 (5): 7–13. doi:10.17010/ijom/2015/v45/i5/79934. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- Author Interviews. "Political and Economic Insights | Articles, Interviews, Videos & Information". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 2009-01-23. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

Further reading

- Lawrence, Robert Z. (2002). "Competitiveness". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (1st ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty. OCLC 317650570, 50016270, 163149563

External links

- WEF Global Competitiveness Report

- World Competitiveness Yearbook by IMD Lausanne

- Ireland's National Competitiveness Council

- Croatia's National Competitiveness Council

- Sri Lanka's The Competitiveness Program, Sri Lanka

- U.S. Council on Competitiveness

- Basque Country (Spain) Basque Institute of Competitiveness – Orkestra

- AccountAbility Responsible Competitiveness

- Spanish Competitiveness Council Consejo Empresarial para la Competitividad