Como, Nevada

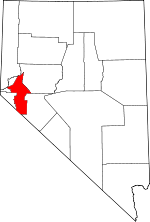

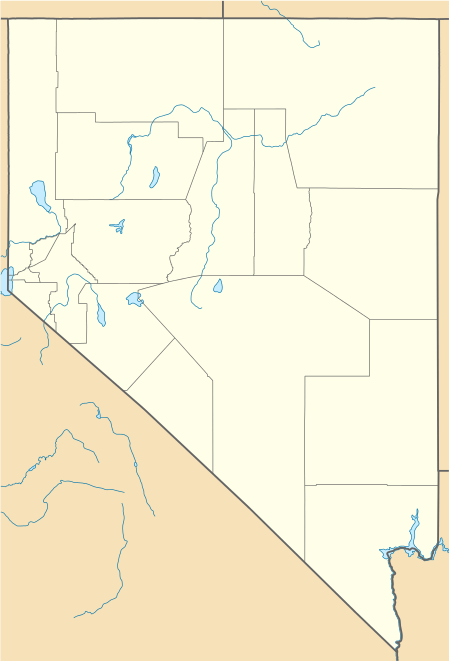

Como is a ghost town in Lyon County, Nevada, in the United States.

Como, Nevada | |

|---|---|

| |

Como  Como | |

| Coordinates: 39°10′21″N 119°28′36″W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Nevada |

| County | Lyon County |

| Elevation | 7,116 ft (2,169 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| GNIS feature ID | 855999 |

History

Gold was found in the Pine Nut Mountains of western Nevada, and in June 1860, the Palmyra mining district was created.

The town of Como was established in late 1862, during the gold rush in Palmyra Mining District. Two bills were under consideration in December, 1862, by the Nevada Territorial Legislature in Carson City, to build a toll road from Carson City to Como.[2] One of the bills was approved on December 18, 1862, providing an act chartering a toll road from Como to the Carson river, and the building of a bridge to cross the river.[3] A correspondent of the Sonoma County Democrat in California, who personally visited Como on February 10, 1863, stated in the March 19, 1863 issue that:

We were surprised in finding Como a flourishing Mining town, having in it four hotels, four dry-good stores, two livery stables, eight saloons, one brewery, besides a tin shop a blacksmith shop and numerous dwelling houses; they are also establishing a school and weekly news paper; the paper we are informed is to be under the supervision of, Messrs. Weston and Abraham, late of the Petaluma Journal. I. D. Cross formerly a merchant of Petaluma, is proprietor of the National Hotel; which as a first class house of refreshments is second to none this side the Sierra Nevada slope.[4]

The town eventually reached a population of as many as "several thousand" people.[5] Como's first rock mill, a steam driven contraption called "The Solomon Davis," arrived with much fanfare in 1863. Although several sources have stated that Como was the first seat of Lyon County, nearby Dayton was officially appointed as the first county seat by the Nevada Territorial Legislative Assembly on November 29, 1861.[6]

New mineral discoveries a short distance away led to the platting of the Como town site, while the site of Palmyra waned. Tunnels were opened and a small mill was built by J.D. Winters. But Winter's efforts to make a profit proved to be unsuccessful and he later drifted to Virginia City, becoming an employee of the Yellow Jacket Mine.[7]

The business sector of the camp had all the usual amenities of frontier life. A highlight of town was the Cross Hotel, a first class establishment with a parlor, bar, carpeted rooms, and a meeting hall. Como had a newspaper, The Como Sentinel, published between April 16, 1864 to July 9, 1864 by T.W. Abraham and H.L. Weston (the latter formerly of the Petaluma California Journal.) After the last issue of the Como Sentinel, Abraham and Weston went on to publish the Lyon County Sentinel at nearby Dayton.[8]

Probably the most notable of Como's residents was Alfred Doten, one of the members of a group of writers to come out of Nevada known as the Sagebrush School. Doten moved to Nevada in 1863 and became a reporter on the Como Sentinel. He later reported for Virginia Daily Union, Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, and Gold Hill Daily News, which he bought in 1872 and guided to a legacy as one of the leading newspapers of the Comstock Mining District. In addition to his journalistic efforts, Doten is known for his exhaustive private diaries. He began writing them when he boarded a ship to California in 1849 and continued until the last day of his life in 1903.[9]

Como's post office operated during two periods, opening originally December 30, 1879 and closing January 3, 1881. During a subsequent revival of the old camp, another post office operated between May 29, 1903 to February 28, 1905.[7][10]

Perhaps the most famous resident of the Como region was Chief Truckee, father of Chief Winnemucca, and befriender of white men. He was the purported savior of emigrant wagon trains and a scout for Kit Carson and John C. Frémont.[11] Today the site is totally abandoned and with only some foundations of the old buildings remaining. In addition to abandoned mines and ghost ruins of the old town, the region also contains rock shelters utilized by Native American tribal people, and petroglyphs done by them at some time in the past.[11]

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Como

- "Letters from Nevada [From Our Special Correspondent]". Sacramento Daily Union (Volume 24, Number 3664). Sacramento, California. December 18, 1862. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "Letter from Nevada [From Our Special Correspondent]". Sacramento Daily Union (Volume 24, Number 3666). Sacramento, California. December 22, 1862. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Oregon Intelligencer (March 19, 1863). "Our Nevada Correspondence". Sonoma County Democrat (Volume VII, Number 23). Santa Rosa, California. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- Cutler, H. C. [Harry] (April 13, 1912). "Como, Nevada". Mining and Scientific Press. 104 (15): 539–540. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- Laws of the Territory of Nevada passed at the first regular session of the Legislative Assembly. San Francisco, CA: Valentine & Co. 1862. pp. 289–291. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- "Como - Nevada ghost town". ghostttowns.com. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- Paher, Stanley W (1970). Nevada Ghost Towns and Mining camps. Howell North. p. 71.

- "The Journals of Alfred Doten, 1843-1903 (Online Edition)". University of Nevada Press. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Como Post Office

- Carl Briggs (August 1971). "Muted mills of Como". Desert Magazine. Retrieved 2013-07-06.