Common blanket octopus

The common blanket octopus or violet blanket octopus (Tremoctopus violaceus) is a large octopus of the family Tremoctopodidae found worldwide in the epipelagic zone of warm seas. The degree of sexual dimorphism in this species is very high, with females growing to two meters in length, whereas males, the first live specimen of which was seen off the Great Barrier Reef in 2002, grow to about 2.4 cm. Individual weights of males and females differ by a factor of about 10,000.[3]

| Common blanket octopus | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Octopoda |

| Family: | Tremoctopodidae |

| Genus: | Tremoctopus |

| Species: | T. violaceus |

| Binomial name | |

| Tremoctopus violaceus Chiaje, 1830 | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Males and small females of less than 7 cm have been reported to carry with them the tentacles of the Portuguese man o' war. It is speculated that these tentacles serve both as a defensive mechanism and possibly as a method of capturing prey. This mechanism is no longer useful at larger sizes, which may be why males of this species are so small. The web between the arms of the mature female octopus serves as a defensive measure as well, making the animal appear larger, and being easily detached if bitten into by a predator.[3]

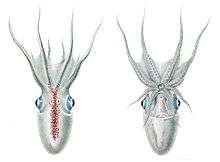

Ventral view of large female

Ventral view of large female Dorsal view of large female

Dorsal view of large female Dorsal view of female

Dorsal view of female Lateral view of adult male with hectocotylus

Lateral view of adult male with hectocotylus

Mating Behavior

The third right arm in male blanket octopuses is called the hectocotylus, which has a sperm-filled pouch between the arms. When the male is ready to mate, the pouch ruptures, and sperm is released into the arm. He then cuts this arm off and gives it to a female. It’s likely that the male dies after mating. The female stores the arm in her mantle to be used when she is ready to fertilize her eggs. She may store several hectocotyluses from different males at once.[4]

The common blanket octopus exhibits one of the highest degrees of sexual size-dimorphism found in large animals. There are several theories as to why this developed. It is advantageous for females to be big; their large eggs take a lot of energy to maintain. The bigger a female is, the more eggs she can carry, and she can birth more offspring that could potentially survive to adulthood. Sperm does not require much energy or space to maintain, so males do not face the same pressure to be big. The use of the Portuguese man o' war tentacles is only effective in smaller animals, so males may have faced selective pressure to remain small in order to continue to utilize this defense.[5]

Defense Mechanisms

Predators of the common blanket octopus include the blue shark,[6] tuna,[7] and the billfish.[7] Female blanket octopuses can roll up and unfurl their webbed blanket as needed.[8] The blanket serves to make the octopus look bigger, and the females can also sever the blanket off to distract predators.[9]

The male blanket octopuses was first observed to be using Portuguese man o' war stingers in 1963. The octopus has Portuguese man o' war tentacles attached to its four dorsal arms. It is unknown whether the blanket octopus is immune to the toxins in the stingers or if they only hold the stingers at insensitive tissue. The use of these tentacles could serve both as defensive and offensive mechanisms. The toxin from the Portuguese man o' war wards off predators, but it could also be used to catch prey.[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tremoctopus violaceus. |

- Allcock, L. (2014). "Tremoctopus violaceus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T174487A1415800. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T174487A1415800.en. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Sweeney, M.J. & R.E. Young (2004). Taxa Associated with the Family Tremoctopodidae Tryon, 1879. Tree of Life Web Project.

- Shapiro, Leo. "Facts about Common Blanket Octopus". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Norman, M. D.; Paul, D.; Finn, J.; Tregenza, T. (2002-12-01). "First encounter with a live male blanket octopus: The world's most sexually size‐dimorphic large animal". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 36 (4): 733–736. doi:10.1080/00288330.2002.9517126. ISSN 0028-8330.

- Norman, M. D.; Paul, D.; Finn, J.; Tregenza, T. (2002-12-01). "First encounter with a live male blanket octopus: The world's most sexually size‐dimorphic large animal". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 36 (4): 733–736. doi:10.1080/00288330.2002.9517126. ISSN 0028-8330.

- Teodoro, Vaske (2009). "Feeding habits of the blue shark (Prionace glauca) off the coast of Brazil". Biota Neotropica. 9: 1–6. ProQuest 215438352.

- Tsuchiya, K (1998). "Cephalopods eaten by pelagic fishes in the tropical East Pacific, with special reference to the feeding habitat of pelagic fish" (PDF). La Mer. 36: 57–66.

- "The Blanket Octopus and it's AMAZING Blanket!!". YouTube. 2019.

- Thomas, Ronald F. (1977). "Systematics, Distribution, and Biology of Cephalopods of the Genus Tremoctopus (Octopoda: Tremoctopodidae)". www.ingentaconnect.com.

- Jones, Everet C. (1963-02-22). "Tremoctopus violaceus Uses Physalia Tentacles as Weapons". Science. 139 (3556): 764–766. doi:10.1126/science.139.3556.764. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17829125.

- Powell A W B, New Zealand Mollusca, William Collins Publishers Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand 1979 ISBN 0-00-216906-1