Committee on Commercial and Industrial Policy

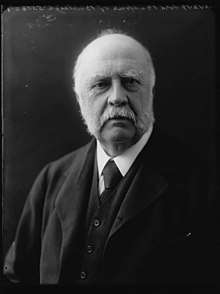

The Committee on Commercial and Industrial Policy was a British First World War government committee chaired by Lord Balfour of Burleigh from 1916 to 1918. It was appointed to devise recommendations for Britain's postwar economic policies.

Background

The Paris Economic Conference of the Allied Powers had resolved to damage the Central Powers economically.[1] The Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith, appointed the Committee in July 1916 in order to implement the Paris Resolutions.[1]

The committee included W. A. S. Hewins (Conservative), Lord Faringdon (Conservative), Alfred Mond (Liberal), Lord Rhondda (Liberal), J. A. Pease (Liberal), George Wardle (Labour), Sir Henry Birchenough and Richard Hazleton (Irish Nationalist).[1][2]

The experience of the war had challenged laissez-faire economic beliefs: at its first meeting (on 25 July 1916) Balfour instructed its members to "cast aside any abstract fiscal dogmas".[3]

Reports

The committee's interim report on certain essential industries argued for a Special Industries Board to scrutinise industrial development and promote the manufacture of strategically essential products. This Board should offer state support for efficient businesses but "failing efficient and adequate output, the Government should itself undertake the manufacture of such articles as may be essential for national safety".[4]

Two interim reports appeared in April and May 1918: the "Interim Report on the Importation of Goods from the Present Enemy Countries after the War" and the "Interim Report on the Treatment of Exports from the United Kingdom and British Overseas Possessions and the Conservation of the Resources of the Empire during the Transitional Period after the War".[5] These recommended that British industries should be protected from dumping after the war; that the enemy's economic domination should be countered; and that key industries should be protected.[5] In return for being protected, industry would be obliged to accept the state's conditions for support: cooperation between employer and employees was recommended, as was profit sharing and state control over industrial combinations.[5]

The committee's final report dealt with the future of British industry both in commercial competitiveness and capacity for war:

It is in our opinion a matter of vital importance that, alike in the old-established industries and in the new branches of manufacture which have arisen during the war, both employer and employed should make every effort to attain the largest possible volume of production, by the increased efficiency of industrial organisation and processes, by more intensive working, and by the adoption of the best and most economical methods of distribution.

[And] it is only by the attainment of this maximum production and efficiency that we can hope to secure a speedy recovery of the industrial and financial position of the United Kingdom and assure its economic stability and progress.[6]

The report also recommended: "The individualist methods hitherto mainly adopted should be supplemented or entirely replaced by co-operation and co-ordination".[7]

Notes

- John Turner, British Politics and the Great War. Coalition and Conflict. 1915-1918 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 341.

- https://archive.org/stream/finalreportofcom00grearich/finalreportofcom00grearich_djvu.txt

- Paul Barton Johnson, Land Fit For Heroes. The Planning of British Reconstruction. 1916-1919 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968), pp. 26-27.

- Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Eyre & Methuen, 1972), pp. 116-117.

- Johnson, p. 27.

- Barnett, p. 117.

- Johnson, p. 86.

References

- Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Eyre & Methuen, 1972).

- Paul Barton Johnson, Land Fit For Heroes. The Planning of British Reconstruction. 1916-1919 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968).

- John Turner, British Politics and the Great War. Coalition and Conflict. 1915-1918 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

Further reading

- Peter Cline, ‘Winding Down the War Economy: British plans for peacetime recovery, 1916-19’, in Kathleen Burk (ed.), War and the State. Transformation of British Government. 1914-19 (London: HarperCollins, 1992), pp. 157-181.