Comédie en vaudevilles

The comédie en vaudevilles (French: [kɔmedi ɑ̃ vodvil]) was a theatrical entertainment which began in Paris towards the end of the 17th century, in which comedy was enlivened through lyrics using the melody of popular vaudeville songs.[1]

Evolution

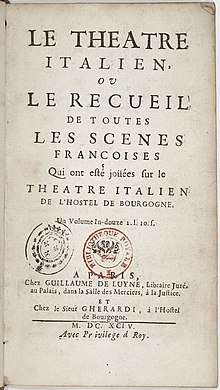

The annual fairs of Paris at St. Germain and St. Laurent had developed theatrical variety entertainments, with mixed plays, acrobatic displays, and pantomimes, typically featuring vaudevilles (see Théâtre de la foire). Gradually these features began to invade established theatres. The Querelle des Bouffons (War of the Clowns), a dispute amongst theatrical factions in Paris in the 1750s, in part reflects the rivalry of this form, as it evolved into opéra comique, with the Italian opera buffa. Comédie en vaudevilles also seems to have influenced the English ballad opera and the German Singspiel.[1]

Vaudeville final

One feature of the comédie en vaudevilles which later found its way into opera was the vaudeville final, a strophic finale in which the characters assemble at the end of the piece with each singing a short verse, often ending with a refrain which everyone would sing, and a final verse with the entire ensemble joining in. Typically the first verse provides the moral of the story, while the intervening verses comment on particular events in the plot, and the final verse appeals directly to audience for its indulgence.[2] Sometimes the verses were also interspersed with dances.[1]

It became a common feature of the earlier opéras comiques, such as those written by Charles Simon Favart[2] or composed by Egidio Duni, Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny, and François-André Danican Philidor, and began to frequently utilize new music, although still labelled "vaudeville".[1] The vaudeville final was almost never used in works presented at the Comédie-Française or the Académie Royale de Musique, and the exceptions are comedies, an example at the former being Pierre Beaumarchais's play Le mariage de Figaro (1784), which ends with a vaudeville, and at the latter, Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Le devin du village (1752), which has a vaudeville final. Although it fell out of style at the Comédie-Italienne around the time of the French Revolution,[2] the tradition was carried into the early 19th century at the popular theatres on the Boulevard du Temple, and elsewhere in Paris, in particular at the Théâtre du Vaudeville.[1]

The style can be discerned in many operas, although with newly composed music, including Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice (1762),[2] Haydn's Orlando paladino (1782), and Mozart's Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782),[2] Der Schauspieldirektor (1786),[3] and Don Giovanni (1788),[1] as well as later works, such as Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia (1816),[2] Gilbert and Sullivan's Trial by Jury (1875), Verdi's Falstaff (1893),[2] Ravel's L'heure espagnole (1911)[2] and Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress (1951).[2]

References

- Barnes 2001.

- Bartlet 1992.

- Oxford Dictionary 1992.

Sources

- Barnes, Clifford, "Vaudeville" in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2001.

- "Vaudeville" in The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, 1992. ISBN 978-0-19-869164-8.

- M. Elizabeth C. Bartlet, "Vaudeville final" in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, 1992. ISBN 978-1-56159-228-9. Also at Oxford Music Online (subscription required).