Colonial government in the Thirteen Colonies

The governments of the Thirteen Colonies of British America developed in the 17th and 18th centuries under the influence of the British constitution. After the Thirteen Colonies had become the United States, the experience under colonial rule would inform and shape the new state constitutions and, ultimately, the United States Constitution.[1]

The executive branch was led by a governor, and the legislative branch was divided into two houses, a governor's council and a representative assembly. In royal colonies, the governor and the council were appointed by the British government. In proprietary colonies, these officials were appointed by proprietors, and they were elected in charter colonies. In every colony, the assembly was elected by property owners.

In domestic matters, the colonies were largely self-governing; however, the British government did exercise veto power over colonial legislation. Diplomatic affairs were handled by the British government, as were trade policies and wars with foreign powers (wars with Native Americans were generally handled by colonial governments).[2] The American Revolution was ultimately a dispute over Parliament's right to enact domestic legislation for the American colonies. The British government's position was that Parliament's authority was unlimited, while the American position was that colonial legislatures were coequal with Parliament and outside of its jurisdiction.

Relation to the British government

By the start of the American Revolution, the thirteen colonies had developed political systems featuring a governor exercising executive power and a bicameral legislature made up of a council and an assembly. The system was similar to the British constitution, with the governor corresponding to the British monarch, the council to the House of Lords and the assembly to the House of Commons.[3]

Crown

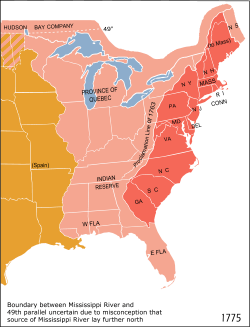

The thirteen colonies were all founded with royal authorization, and authority continued to flow from the monarch as colonial governments exercised authority in the king's name.[4] A colony's precise relationship to the Crown depended on whether it was a charter colony, proprietary colony or royal colony as defined in its colonial charter. Whereas royal colonies belonged to the Crown, proprietary and charter colonies were granted by the Crown to private interests.[5]

Control over a charter or corporate colony was granted to a joint-stock company, such as the Virginia Company. Virginia, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island were founded as charter colonies. New England's charter colonies were virtually independent of royal authority and operated as republics where property owners elected the governor and legislators.[6] Proprietary colonies were owned and governed by individuals. To attract settlers, however, proprietors agreed to share power with property owners.[7] Maryland, South Carolina, North Carolina, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania were founded as proprietary colonies.[8]

In 1624, Virginia became the first royal colony when the bankrupt Virginia Company's charter was revoked.[9] Overtime, more colonies transitioned to royal control. By the start of the American Revolution, all but five of the thirteen colonies were royal colonies. Maryland, Pennsylvania and Delaware remained proprietary, while Rhode Island and Connecticut continued as corporate colonies.[4]

Historian Robert Middlekauff describes royal administration of the colonies as inadequate and inefficient because lines of authority were never entirely clear. Before 1768, responsibility for colonial affairs rested with the Privy Council and the Secretary of State for the Southern Department. The Secretary relied on the Board of Trade to supply him with information and pass on his instructions to colonial officials. After 1768, the Secretary of State for Colonial Affairs was responsible for supervising the colonies; however, this ministry suffered from ineffective secretaries and the jealousy of other government ministers.[10]

Parliament

Parliament's authority over the colonies was also unclear and controversial in the 18th century.[11] As English government evolved from government by the Crown toward government in the name of the Crown (the King-in-Parliament),[12] the convention that the colonies were ruled solely by the monarch gave way to greater involvement of Parliament by the mid 1700s. Acts of Parliament regulated commerce (see Navigation Acts), defined citizenship, and limited the amount of paper money issued in the colonies.[13]

The British government argued that Parliament's authority to legislate for the colonies was unlimited. This was stated explicitly in the Declaratory Act of 1766.[12] The British also argued that the colonists, while not actually represented in Parliament, were nonetheless virtually represented.[14] The American view, shaped by Whig political philosophy, was that Parliament's authority over the colonies was limited.[15] While the colonies initially recognized Parliament's right to legislate for the whole empire—such as on matters of trade—they argued that Parliamentary taxation was a violation of the principle of taxation by consent since consent could only be granted by the colonists' own representatives. In addition, Americans argued that the colonies were outside of Parliament's jurisdiction and that the colonists owed allegiance only to the Crown. In effect, Americans argued that their colonial legislatures were coequal—not subordinate—to Parliament.[16] These incompatible interpretations of the British constitution would become the central issue of the American Revolution.[17]

Judicial appeals

In the United Kingdom, Parliament (technically, the King- or Queen-in-Parliament) was also the highest judicial authority, but appellate jurisdiction over the British colonies ended up with a series of committees of the Privy Council (technically, the King- or Queen-in-Council). In 1679, appellate jurisdiction was given to the Board of Trade, followed by an Appeals Committee in 1696.[18]

The Appeals Committee of the Privy Council was severely flawed because its membership was actually a committee of the whole of the Privy Council, of whom a quorum was three. Even worse, many Privy Councillors were not lawyers, all Privy Councillors had equal voting power on appeals, and there was no requirement that any of the Privy Councillors hearing a particular appeal had to be a lawyer. As a result, parties to appeals could and did try to tilt the outcome of appeals in their favor by persuading nonlawyer Privy Councillors to show up for the hearings on their appeals. For this reason, the Appeals Committee fell into disrepute among better-informed lawyers and judges in the colonies.[18]

Branches

Governor

In royal colonies, governors were appointed by the Crown and represented its interests. Before 1689, governors were the dominant political figures in the colonies.[19] They possessed royal authority transmitted through their commissions and instructions.[20] Among their powers included the right to summon, prorogue and dissolve the elected assembly. Governors could also veto any bill proposed by the colonial legislature.[21]

Gradually, the assembly successfully restricted the governor's power by asserting for itself control over money bills, including the salaries of the governor and other officials.[21] Therefore, a governor could find his salary withheld by an uncooperative legislature. Governors were often placed in an untenable position. Their official instructions from London demanded that they protect the Crown's power—the royal prerogative—from usurpation by the assembly; at the same time, they were also ordered to secure more colonial funding for Britain's wars against France. In return for military funding, the assemblies often demanded more power.[22]

To gain support for his agenda, the governor distributed patronage. He could reward supporters by appointing them to various offices such as attorney general, surveyor-general or as a local sheriff. These offices were sought after as sources of prestige and income. He could also reward supporters with land grants. As a result of this strategy, colonial politics was characterized by a split between a governor's faction (the court party) and his opposition (the country party).[22]

Council

The executive branch included an advisory council to the governor that varied in size ranging from ten to thirty members.[21][23] In royal colonies, the Crown appointed a mix of placemen (paid officeholders in the government) and members of the upper class within colonial society. Councilors tended to represent the interests of businessmen, creditors and property owners in general.[24] While lawyers were prominent throughout the thirteen colonies, merchants were important in the northern colonies and planters were more involved in the southern provinces. Members served "at pleasure" rather than for life or fixed terms.[25] When there was an absentee governor or an interval between governors, the council acted as the government.[26]

The governor's council also functioned as the upper house of the colonial legislature. In most colonies, the council could introduce bills, pass resolutions, and consider and act upon petitions. In some colonies, the council acted primarily as a chamber of revision, reviewing and improving legislation. At times, it would argue with the assembly over the amendment of money bills or other legislation.[24]

In addition to being both an executive and legislative body, the council also had judicial authority. It was the final court of appeal within the colony. The council's multifaceted roles exposed it to criticism. Richard Henry Lee criticized Virginia's colonial government for lacking the balance and separation of powers found in the British constitution due the council's lack of independence from the Crown.[25]

Assembly

The lower house of a colonial legislature was a representative assembly. These assemblies were called by different names. Virginia had a House of Burgesses, Massachusetts had a House of Deputies, and South Carolina had a Commons House of Assembly.[27][28] While names differed, the assemblies had several features in common. Members were elected annually by the propertied citizens of the towns or counties. Usually they met for a single, short session; but the council or governor could call a special session.[26]

As in Britain, the right to vote was limited to men with freehold "landed property sufficient to ensure that they were personally independent and had a vested interest in the welfare of their communities".[29] Due to the greater availability of land, the right to vote was more widespread in the colonies where by one estimate around 60 percent of adult white males could vote. In England and Wales, only 17–20 percent of adult males were eligible. Six colonies allowed alternatives to freehold ownership (such as personal property or tax payment) that extended voting rights to owners of urban property and even prosperous farmers who rented their land. Groups excluded from voting included laborers, tenant farmers, unskilled workers and indentured servants. These were considered to lack a "stake in society" and to be vulnerable to corruption.[30]

Tax issues and budget decisions originated in the assembly. Part of the budget went toward the cost of raising and equipping the colonial militia. As the American Revolution drew near, this subject was a point of contention and conflict between the provincial assemblies and their respective governors.[26]

The perennial struggles between the colonial governors and the assemblies are sometimes viewed, in retrospect, as signs of a rising democratic spirit. However, those assemblies generally represented the privileged classes, and they were protecting the colony against unreasonable executive encroachments. Legally, the crown governor's authority was unassailable. In resisting that authority, assemblies resorted to arguments based upon natural rights and the common welfare, giving life to the notion that governments derived, or ought to derive, their authority from the consent of the governed.[31]

Union proposals

Before the American Revolution, attempts to create a unified government for the thirteen colonies were unsuccessful. Multiple plans for a union were proposed at the Albany Congress in 1754. One of these plans, proposed by Benjamin Franklin, was the Albany Plan.[32]

Demise

During the American Revolution, the colonial governments ceased to function effectively as royal governors prorogued and dissolved the assemblies. By 1773, committees of correspondence were governing towns and counties, and nearly all the colonies had established provincial congresses, which were legislative assemblies acting outside of royal authority. These were temporary measures, and it was understood that the provincial congresses were not equivalent to proper legislatures.[33]

By May 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress felt that a permanent government was needed. On the advice of the Second Continental Congress, Massachusetts once again operated under the Charter of 1691 but without a governor (the governor's council functioned as the executive branch).[34] In the fall of 1775, the Continental Congress recommended that New Hampshire, South Carolina and Virginia form new governments. New Hampshire adopted a republican constitution on January 5, 1776. South Carolina's was adopted on March 26 and Virginia's on June 29.[35]

In May 1776, the Continental Congress called for the creation of new governments "where no government sufficient to the exigencies of their affairs have been hitherto established" and "that the exercise of every kind of authority under the ... Crown should be totally suppressed".[36] The Declaration of Independence in July further encouraged the states to form new governments, and most states had adopted new constitutions by the end of 1776. Because of the war, Georgia and New York were unable to complete their constitutions until 1777.[35]

See also

- Colonial history of the United States

- Proprietary governor

- Proprietary House

References

Notes

- Green 1930, p. ix.

- Cooke (1993) vol 1 part 4

- Johnson 1987, pp. 349-350.

- Middlekauff 2005, p. 27.

- Taylor 2001, pp. 136-137.

- Taylor 2001, p. 247.

- Taylor 2001, pp. 246-247.

- Taylor 2001, pp. 140, 263.

- Taylor 2001, p. 136.

- Middlekauff 2005, pp. 27-28.

- Middlekauff 2005, p. 28.

- Green 1930, p. 3.

- Johnson 1987, p. 342.

- Green 1930, p. 4.

- Hulsebosch 1998, p. 322.

- Johnson 1987, p. 353.

- Green 1930, p. 2.

- Howell 2009, pp. 7–13.

- Greene 1961, p. 451.

- Bonwick 1986, p. 358.

- Morton 1963, p. 438.

- Taylor 2001, pp. 286–288.

- "Colonial Councils". Dictionary of American History. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- Harrold 1970, pp. 282-283.

- Harrold 1970, p. 282.

- Cooke (1993) vol 1 part 4

- "General Court, Colonial". Dictionary of American History. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Edgar, Walter (November 26, 2018). ""C" is for Commons House of Assembly (1670-1776)". South Carolina Public Radio. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Ratcliff 2013, p. 220.

- Ratcliff 2013, p. 220-221.

- Green 1930, pp. 21–22.

- Middlekauff 2005, pp. 31-32.

- Wood 1998, pp. 313–317.

- Wood 1998, pp. 130, 133.

- Wood 1998, pp. 133.

- Wood 1998, pp. 132.

Sources

- Bonwick, Colin (December 1986). "The American Revolution as a Social Movement Revisited". Journal of American Studies. British Association for American Studies. 20 (3): 355–373. JSTOR 27554789 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooke, Jacob Ernest, ed. (1993). Encyclopedia of the North American Colonies. 3 Volumes. C. Scribner's Sons. ISBN 9780684192697.

- Green, Fletcher Melvin (1930). Constitutional Development in the South Atlantic States, 1776-1860: A Study in the Evolution of Democracy. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781584779285.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greene, Jack P. (November 1961). "The Role of the Lower Houses of Assembly in Eighteenth-Century Politics". The Journal of Southern History. Southern Historical Association. 27 (4): 451–474. doi:10.2307/2204309. JSTOR 2204309 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrold, Frances (July 1970). "The Upper House in Jeffersonian Political Theory". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Virginia Historical Society. 78 (3): 281–294. JSTOR 4247579 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howell, P.A. (2009). The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council: 1833-1876 Its Origins, Structure and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521085595.

- Hulsebosch, Daniel J. (Summer 1998). "Imperia in Imperio: The Multiple Constitutions of Empire in New York, 1750-1777". Law and History Review. American Society for Legal History. 16 (2): 319–379. doi:10.2307/744104. JSTOR 744104 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson, Richard R. (September 1987). ""Parliamentary Egotisms": The Clash of Legislatures in the Making of the American Revolution". The Journal of American History. Organization of American Historians. 74 (2): 338–362. doi:10.2307/1900026. JSTOR 1900026 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Middlekauff, Robert (2005). The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford History of the United States. Volume 3 (revised ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531588-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morton, W. L. (July 1963). "The Local Executive in the British Empire 1763-1828". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 78 (308): 436–457. JSTOR 562144 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ratcliff, Donald (Summer 2013). "The Right to Vote and the Rise of Democracy, 1787—1828". Journal of the Early Republic. Society for Historians of the Early American Republic. 33 (2): 219–254. JSTOR 24768843 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Alan (2001). American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Penguin History of the United States. Volume 1. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-101-07581-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wood, Gordon S. (1998). The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4723-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Andrews, Charles M. Colonial Self-Government, 1652-1689 (1904) full text online

- Andrews, Charles M. The Colonial Period of American History (4 vol. 1934-38), the standard overview to 1700

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Origins of American Politics (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968): an influential book arguing that the roots of the American Revolution lie in the colonial legislatures' struggles with the governors.

- Dickerson, Oliver Morton (1912). American Colonial Government, 1696-1765. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company.

- Dinkin, Robert J. Voting in Provincial America: A Study of Elections in the Thirteen Colonies, 1689-1776 (1977)

- Green, Fletcher Melvin (1930). Constitutional Development in the South Atlantic States, 1776-1860: A Study in the Evolution of Democracy. U. of North Carolina press. ISBN 9781584779285.

- Greene, Jack P. Negotiated Authorities: Essays in Colonial Political and Constitutional History (1994)

- Hawke, David F.; The Colonial Experience; 1966, ISBN 0-02-351830-8. textbook

- Nagl, Dominik. No Part of the Mother Country, but Distinct Dominions - Law, State Formation and Governance in England, Massachusetts und South Carolina, 1630-1769 (2013). Archived 2016-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Main, Jackson Turner (1967). The Upper House in Revolutionary America, 1763-1788. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Middleton, Richard, and Anne Lombard. Colonial America: A History to 1763 (4th ed. 2011) excerpt and text search

- Osgood, Herbert L. The American colonies in the seventeenth century, (3 vol 1904-07)' vol. 1 online; vol 2 online; vol 3 online

- Osgood, Herbert L. The American colonies in the eighteenth century (4 vol, 1924–25)