Col di Lana

The Col di Lana is a mountain of the Fanes Group in the Italian Dolomites. The actual peak is called Cima Lana and situated in the municipality of Livinallongo del Col di Lana (German: Buchenstein) in the Province of Belluno, Veneto region.

| Col di Lana | |

|---|---|

Col di Lana (left) and the neighbouring Monte Sief (right) | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,462 m (8,077 ft) |

| Prominence | 265 m (869 ft) |

| Coordinates | 46°29′24″N 11°58′12″E |

| Geography | |

Col di Lana Italy | |

| Location | Province of Belluno, Italy |

| Parent range | Dolomites, Fanes group |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Over the Valparola Pass, over saddle of Monte Sief, then over the Dente del Sief (German: Knotz) to the summit |

History

World War I

During World War I the mountain, alongside the neighbouring Monte Sief, was the scene of heavy fighting between Austria-Hungary and Italy. It is now a memorial to the War in the Dolomites.

During the years of 1915/16, Italian troops from 12 infantry and 14 Alpini companies repeatedly attempted to storm the peak, defended first by the German Alpenkorps and later by Austro-Hungarian regiments. These attempts resulted in heavy losses; 278 Italians died due to avalanches alone. On 8 November 1915 the Italians, under the command of Lt. Col. Giuseppe Garibaldi II conquered the summit but then could only mount a weak defence with rag-tag units against a well orchestrated pincer manoeuvre: the top of the Col di Lana fell back to Austro-Hungarian troops early the next day. A terrible winter then set in, doing its fair share of killing. However this is not the only reason that the Italians dubbed it "Col di Sangue", "Blood Mountain". Like all sides in the First World War, the Italian Army sought to conquer the summit with relatively large forces, paying a high price in casualties.

In 1916, Col di Lana became the site of fierce mine warfare on the Italian Front. Lieutenant Caetani of the Italian engineers developed a plan for mining the peak, which was executed silently using hand-operating drilling machines and chisels. At the start of 1916, the Austro-Hungarian army learned through an artillery observer on Pordoi Pass that the Col di Lana summit had been mined. The Austro-Hungarians began a counter mine, and exploded this on 6 April 1916. The counter mine was, however, too far away from the Italian explosive tunnel. This was laid with five tonnes of blasting gelatin. On the night of 16/17 April 1916, the 5th Company of the 2nd Tyrolean Kaiserjäger regiment was relieved by the 6th Company, under Oberleutnant Anton von Tschurtschenthaler. The struggle reached its zenith on the night of 17/18 April 1916, when at around 23:30 the summit was blasted. The Austro-Hungarians under Tschurtschenthaler then had to surrender the mountain; however they were able to maintain a position on Monte Sief, which is linked to Col di Lana by a ridge, which was cut in two by a mine fired on 21 October 1917 by Austro-Hungarian soldiers, thereby obstructing the Italian breakthrough in the area.

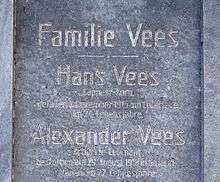

Memorial

Today a memorial chapel stands on the summit as a memorial to the soldiers that fell in battle. The remains of a barracks and decaying gun and communications trenches have been left behind from the war. There is also a small war museum on the mountain.

The route is from Pieve di Livinallongo (1,465 m) via the Rifugio Pian della Lasta (1,835 m); there is a road as far as the hut.

References

- Anton (Toni) von Tschurtschenthaler: Col di Lana 1916, Schlern-Schriften Vol. 179, 1957

- Generalmajor Viktor Schemfil: Col di Lana - Geschichte der Kämpfe um den Dolomitengipfel 1915-1917; Schriftreihe zur Zeitgeschichte Tirols Vol. 3, Buchdienst Südtirol E. Kienesberger Nürnberg 1983, ISBN 0-00-228421-9

- Alberto Giacobbi: Il fronte delle Dolomiti (1915/17), Verlag Ghedina, 2005

- Walther Schaumann: Schauplätze Des Gebirgskrieges 1915-17. Vol. 1/2: Westliche Dolomiten. ISBN 978-88-7691-020-3

- Heinz von Liechem: Gebirgskrieg 1915-1918 Band 2, Verlagsanstalt Athesia 1997, ISBN 88-7014-236-1

- Gunther Langes: Die Front in Fels und Eis, Athesia-Tappeiner Verlag 2016, ISBN 978-88-6839-089-1

- Erik Durschmied: Totentanz am Col di Lana, Athesia-Tappeiner Verlag 2017, ISBN 978-88-6839-268-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Col di Lana. |