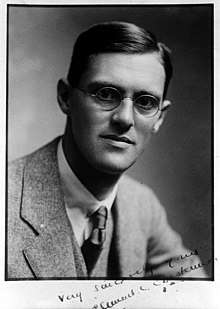

Clement Clapton Chesterman

Sir Clement Clapton Chesterman, MBBS, FRCP, OBE (30 May 1894 – 20 July 1983) was a prominent writer, humanitarian and physician. He was a medical missionary for the Baptist Missionary Society that served in the Belgian Congo, more specifically Yakusu. He was responsible for the establishment of a hospital, community-based dispensaries and training centres of medical auxiliaries. Chesterman's network of health dispensaries employed preventive medicine using the new drug tryparsamide to combat the prevalent issue of sleeping sickness in the area. His implementation of mass chemotherapy was extremely successful in eliminating the disease. Such success led to his methods being widely adopted in Africa, making Chesterman a prominent contributor to the field of tropical medicine. In 1974 he was knighted (Knight Bachelor) by Queen Elizabeth.

Clement C. Chesterman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 30 May 1894 Bath Somerset, England |

| Died | 20 July 1983 (aged 89) Hampstead, England |

| Nationality | English |

Personal life

Early Life and family

Chesterman was born on 30 May 1894 in Bath, Somerset, England. His parents were William Thomas Chesterman and Anne Greaves Chesterman. He was born into a large Bath family that had a history of strong Christian connections going back to Neuchatel, Switzerland, and to the west country. The members of Chesterman's family were members of Manvers Street Baptist Church in Bath, which was the church where Chesterman was baptised as a young man on 31 January 1909.

On 7 July 1917 Chesterman was married to Winifred Lucy Spear at Manvers Street Baptist Church. From their marriage, they had five children and they were Henry David Chesterman, Frederick Clement Chesterman, Hilda Heather Chesterman, Michael Paul Chesterman, and Elizabeth Hazel Chesterman.

Education

Chesterman was well-educated throughout his life. He was educated at Victoria College from 1905 to 1907 and then at Monkton Combe School from 1907 to 1911. Chesterman then went to study medicine at the University of Bristol from 1911 to 1917.

His interest in tropical medicine stemmed from his experiences as a medical student dresser in Serbia during the World War I, where he treated victims with a variety of tropical scourges. His desire to pursue a career in tropical medicine especially stemmed from his responsibility for a malaria diagnostic service under his apprenticeship to Major Philip Bahr in Palestine. During his apprenticeship, he witnessed a lot of typhus and dysentery. He enrolled for a tropical medicine course at the London Dock Hospital after demobilisation. Afterwards, he pursued and received the Cambridge Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, as well as the London MD in tropical medicine.

Military Service and honours

In 1915, Chesterman served with the first British field ambulance in Serbia, while also serving with the Royal Army Medical Corps in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria from 1917 to 1918. Additionally, he received the Serbian Red Cross medal and was given the position of the Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1919 in recognition of his efforts with malarial patients among the troops in Damascus.

Mission

Calling

Two people Chesterman looked up to were David Livingstone and Albert Schweitzer. After reading On the edge of the Primaeval Forest, Chesterman wrote an appreciation letter to Albert Schweitzer from his mission station at Yakusu, which was 2,000 miles east of Lambaréné, in the former Belgian Congo and this letter was acknowledged by Schweitzer. Chesterman similarly admired the work of David Livingstone and this could be seen through his rejection of a promising academic career to follow the footsteps of Livingstone. As he travelled by ship to and from Serbia in 1915, he caught his first glimpse of Africa, which sparked his fascination. In 1955, as chairman of the Albert Schweitzer Fund in Great Britain, he hosted Albert Schweitzer's visit to Great Britain including a visit to Buckingham Palace.[1]

Service

In August 1920, Chesterman journeyed to the Belgian Congo as a medical missionary of the Baptist Missionary Society immediately after he completed his studies in tropical medicine at the Albert Dock Hospital. On his arrival, he was given the position of the head of a new medical mission at Yakusu. Through the help of Arnold, Chesterman's brother who was a qualified architect, a new hospital was successfully constructed. Medical missionary service grew in the region through the 1960s.[2]

Within the riverside villages nearby Yakusu, a third of the population was suffering from an infection known as sleeping sickness. Through his treatment centres, Chesterman began a weekly programme of injection using the supply of a new drug called tryparsamide. He worked in collaboration with the Belgian authorities and such a partnership allowed for the development of a network of village dispensaries staffed by Congolese auxiliaries. Their methodical use of this new drug was so effective that it nearly eliminated sleeping sickness from the Yakusu region within seven years. Such an outcome raised Chesterman's status and he became perceived as a "powerful medicine man" by the locals.

Soon after, Chesterman made use of both chemotherapy and nursing auxiliaries to fight the epidemic of yaws in the same region. Rather than relying on the improvement of standards of living and public hygiene, Chesterman advocated for the mass use of chemotherapy, which complements his support for the motto "prevention is better than cure". He also believed that the development of a programme of simple health posts that functioned through the service of trained and supervised medical auxiliaries would support the adoption of Western medicine in tropical Africa. This model would be further developed by Stanley George Browne in Nigeria leading to Chesterman's design being implemented to manage infectious diseases across the continent.[3]

Life after missions

In 1936, Chesterman departed from Yakusu and left his missionary work behind. He was called by the Baptist Missionary Society to go to London to take up the position of the office of medical secretary and medical officer. During his time at the base in London, he participated in policy formulation in both missionary and colonial medicine.

On his return, Chesterman involved himself in a variety of efforts that led to his legacy. In 1938, Chesterman attended the World Council of Churches meeting in Madras, where he persuaded Ida Scudder to allow the admittance of men students to the Vellore Women's Medical College. Chesterman joined a general practice in Buckinghamshire owing to the emergence of World War II. However, after the war, he became a renowned consultant in the subject of tropical medicine and was in great demand by the Colonial Office, insurance companies and foreign governments. It is reported that he was called to treat Mahatma Ghandhi because of his expertise in tropical medicine.[4]

Chesterman was offered the position of a lecturer in tropical medicine by the Middlesex Hospital. He contributed greatly as an active member of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, and became appointed as the vice-president of the Society from 1951 to 1953. He became the president of the Hunterian Society from 1966 to 1967.[1]

Owing to the lack of books for the purposes of training the auxiliaries through his strategy, Chesterman wrote his own textbook titled African Dispensary Handbook (1929), which was revised and re-issued under the tile Tropical Dispensary Handbook for wider use. His new book was published in seven English editions and was also translated into French, Portuguese and Spanish. Additionally, he published a variety of articles on tropical medicine, as well as In the Service of Suffering, a popular history of medical missions.

In addition to these contributions, he took on more responsibilities and positions: the president of the Medical Missionary Association, vice-president of the Leprosy Mission, supporter of the Friends of Vellore, the chairman of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital Fund, and a member of the colonial advisory medical committee.

During World War II, Chesterman moved his family to Chalfont St Giles in Buckinghamshire. With the passing of the war, he moved to and lived in Hampstead. There, he and his wife became members of Heath Street Baptist Church. He was an honorary Fellow in the Royal Academy of Music. He received the Order of the British Empire in 1917.[1] In 1974 he was knighted (Knight Bachelor) by Queen Elizabeth II in recognition of his overseas medical service. On 20 July 1983 Chesterman died at Bushey Health, Hertfordshire. He was cremated at Hendon, London, on 27 July.

References

- Brit.med.J., 1983, 287, 435: Lancet, 1603, 2, 353; Times, 27 July 1983 (Volume VII, page 96)

- Stanley, Brian. "Chesterman, Sir Clement Clapton (1894–1983), Medical Missionary and Specialist in Tropical Diseases | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography." (1894–1983), Medical Missionary and Specialist in Tropical Diseases | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 10 November 2017, www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-64912?rskey=f7yHXR&result=1.

- Christophers, S. R. “Handbook For The Tropics.” The British Medical Journal, vol. 1, no. 4718, 1951, pp. 1305–1306. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25361088.

- “Sir Clement Chesterman OBE, MD, FRCP, DTM&H.” British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition), vol. 287, no. 6389, 1983, pp. 435–435. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/29511907.

- Chesterman, C. C.(Clement Clapton), Sir. “Indian Village Health.” International Review of Mission, vol. 33, no. 132, 1944, pp. 460–462. EBSCOhost, proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rfh&AN=ATLAiFZK180514002093&site=ehost-live.

- Chesterman, C. C.(Clement Clapton), Sir. “Report of the Medical Commission, 1939.” International Review of Mission, vol. 29, no. 115, July 1940, pp. 414–415. EBSCOhost, proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rfh&AN=ATLAiE58180528002452&site=ehost-live.

- Chesterman, C. C.(Clement Clapton), Sir. “Medical Missions in Belgian Congo.” International Review of Mission, vol. 26, no. 103, July 1937, pp. 378–385. EBSCOhost, proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rfh&AN=ATLAiG0V180528000811&site=ehost-live.

- CHESTERMAN, Clement C. “My Man Sunday.” Reader’s Digest, vol. 51, Sept. 1947, pp. 95–100. EBSCOhost, proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rgr&AN=522753379&site=ehost-live.

- "Munks Roll Details for Clement Clapton (Sir) Chesterman". munksroll.rcplondon.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine | International Leprosy Association – History of Leprosy". leprosyhistory.org. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo – ILEP". 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "The Descendants of John Chesterman". airgale.com.au. Retrieved 7 December 2018.