Cisco Pike

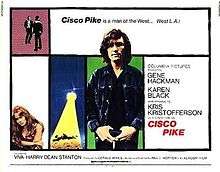

Cisco Pike is a 1972 drama film that was written and directed by Bill L. Norton, and released by Columbia Pictures. The film stars Kris Kristofferson as a musician who, having fallen on hard times, turns to the selling of marijuana and is blackmailed by a police officer (Gene Hackman).

| Cisco Pike | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Bill L. Norton |

| Produced by | Gerald Ayres |

| Written by | Bill L. Norton Robert Towne (uncredited) |

| Starring | Kris Kristofferson Gene Hackman Karen Black Harry Dean Stanton Doug Sahm Viva |

| Music by | Kris Kristofferson (songs) |

| Cinematography | Vilis Lapenieks |

| Edited by | Robert C. Jones |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$800,000 |

The movie, which is Norton's directorial debut and Kristofferson's debut as a leading actor, was filmed in the Los Angeles area in late 1970 and includes several contemporaneous landmarks. It premiered in 1972 to unfavorable reviews and was a box office failure.

Cisco Pike was not officially available on home media until its re-release on DVD in 2006. Since its release, reviews became more favorable as the film earned followers and became a cult classic.

Plot

After his recent arrest for drug dealing, singer Cisco Pike tries to pawn his guitar. The shop owner refuses the guitar and Cisco returns home to find his recent demos have been rejected. He records more and tells his girlfriend Sue about his recent failure. Former customers keep calling him to buy drugs.

Detective Leo Holland has stolen a sizable quantity of high-grade marijuana from a Mexican gang and visits Cisco, who cites his attempt to quit the drugs business. Holland arrests Cisco and then takes him to a garage, where he shows Cisco the stolen marijuana. Cisco then visits his lawyer, who confirms the garage belongs to a person called Betty Hall, apparently related to Holland. The lawyer advises Cisco to avoid Holland but shows further interest when Cisco mentions the high quality of the marijuana.

Holland finds Cisco, tells him he needs US$10,000, and gives him fifty-nine hours to sell the marijuana and in return tells Cisco he may keep any excess money and that he will alter his most recent arrest paperwork if the case goes to trial. Cisco accepts the deal and starts fragmenting the marijuana bricks. Cisco contacts his former customers and proceeds with sales. After one bulk customer spots a solitary figure surveilling them with binoculars and takes off, Cisco confronts Holland, gives him back the bricks, and refuses to work with Holland any further, returning home to work on his demos. Holland is angry and visits Cisco's home; he beats Cisco and threatens to shoot him unless he continues the sales. Cisco agrees and Holland leaves.

Cisco visits his former competitor Brother Buffalo to try to sell the bricks more quickly, and offers him twenty-five kg (55 lb) for a low price. Buffalo tells Cisco he will try to work out a deal with his associates. Cisco then visits his musician friend Rex, who is recording songs at a studio. Rex rejects the demos Cisco previously sent him. Instead, he asks him about the marijuana. Cisco, disappointed, meets Rex's manager to discuss the sale of drugs. Cisco rejects the manager's deal then meets groupie Merna and leaves with her. They pick up Lynn on the way to her father's mansion.

After a brief sexual encounter with the two girls, Cisco continues selling drugs as tensions between him and his girlfriend escalate. He visits Rex's manager, who agrees to pay Cisco's price. The manager tells Cisco he will be paid in two days; Cisco destroys his office until the manager gives him a personal check. Another of Cisco's customers takes him to a major buyer, and Cisco realizes he and his customer are being set up by the police; they escape and are rescued by Sue. Cisco grows increasingly frustrated because he has not been contacted by his potential buyers and is still short of money. Sue finds Cisco's former bandmate Jesse Dupre taking a bath at their home. Being affected by the state of Jesse's drug addiction, Cisco tells Sue he is being blackmailed by a police officer.

Jesse and Cisco travel to Sunset Strip, where they find Merna and Lynn. Merna introduces Cisco to a big buyer, who accepts Cisco's requested price. Later, at a party at Merna's house, Jesse overdoses with heroin and dies. Meanwhile, Holland enters Cisco's house uninvited and stays with Sue, who escapes, leaving Holland inside.

Cisco drives Jesse's body to his home in Venice and finds Sue sleeping in her van. Sue warns him of Holland and Cisco tells Sue of Jesse's death. Cisco leaves Jesse's corpse on a bench. Sue calls 9-1-1 to notify them about the body. Cisco confronts Holland and Sue tells Cisco she is leaving him. Cisco gives the money to a desperate Holland; they are interrupted by the arriving emergency services responding to the call about Jesse's body. Thinking they are coming after him, Holland starts shooting at them and is fatally shot. Sue returns home and Cisco drives away.

Cast

- Kris Kristofferson as Cisco Pike

- Gene Hackman as Detective Leo Holland

- Karen Black as Sue

- Harry Dean Stanton as Jesse Dupre

- Doug Sahm as Rex

- Viva as Mirna

- Joy Bang as Joyce

- Antonio Fargas as Brother Buffalo

- Roscoe Lee Brown as pawnshop owner

Background and production

Following the success of Easy Rider (1969), films depicting the ideals of the counterculture of the 1960s spawned the New Hollywood movement in film. Releases in this style which met a good audience reception in 1970 include Getting Straight, The Strawberry Statement and Five Easy Pieces.[1]

UCLA graduate and Los Angeles–born Bill Norton wrote a draft of a story depicting the relationship between the contemporaneous music and drug scenes.[2] Norton had worked as a director on short films for UCLA's film school, television commercials and rock-and-roll shorts.[3] Norton came into contact with producer Gerald Ayres of Columbia Pictures and pitched the project to him. Ayres then forwarded the script to his friend Robert Towne, who reworked the story and further developed the characters.[2]

Towne added the character of the corrupt police officer who forces Cisco Pike back into the drug world and further expanded the role of Cisco's girlfriend. Norton initially opposed the casting of Karen Black but relented when the studio imposed it as a condition for producing the film. Columbia felt Black's recent Best Supporting Actress nomination in the Academy Awards for Five Easy Pieces would help the promotion of the release.[4] Cisco Pike is Norton's directorial debut.[5]

Kris Kristofferson had made his film debut with a cameo appearance on Dennis Hopper's The Last Movie, which was unreleased at the time of Cisco Pike's production.[6] After his debut performance as a singer at the Los Angeles nightclub The Troubadour, Kristofferson was approached by Fred Roos, the casting director of Five Easy Pieces, who invited him to audition for his film debut for a leading role on Two-Lane Blacktop. Kristofferson, who was signed to Columbia Records, arrived to the appointment intoxicated and left. Kristofferson was next offered Norton's script by Columbia. His peers encouraged him to reject the role and to take acting lessons instead, but he accepted the part, and later said; "I read the script and I could identify with this cat" and that acting is "understanding a character, and then being just as honest as you can possibly be".[7] Gene Hackman accepted the role because he saw it as an opportunity to work in California, close to his wife at the time, Faye Maltese.[5] Kristofferson's friend Harry Dean Stanton also joined the production.[8] Supporting roles included Warhol superstar Viva and Joy Bang.[9]

Filming began on November 2, 1970,[10] initially under the working title Dealer, which was changed to Silver Tongued Devil.[11] Ayres wrote some scenes of the film, and the script and storyline were altered while filming progressed. Editor Robert Jones contributed the ending of the story. Cisco Pike was mostly filmed on location around Venice Beach and its boardwalk.[4] Sunset Strip was also used as a location, and some indoor scenes were filmed at The Troubadour and The Source Restaurant. The mansion of silent-film-era star Pola Negri was used as the home of Viva's character. Filming was affected by intense seasonal rain but the schedule was kept to by shooting in up to three locations daily.[12] During the official post-production process, new scenes were written and filmed partly in New York City.[4]

Filming was over by December 1970.[10] A crew of thirty-five took part in the production, which was one of the smallest Columbia Pictures had used at that point. Norton described the sets to Action (the Directors Guild of America magazine) as "claustrophobic" and said the finished film did not "play on the screen like it played in [his] mind".[3] Post-production was finished by early 1971; Cisco Pike cost less than US$800,000 to produce.[13]

Release and reception

Cisco Pike opened to a limited release on January 14, 1972, two years after its filming.[11] Initial reviews were poor and it was a commercial failure at the box office.[5] Released during the beginning of the war on drugs, Life described the approach of the movie studios and their depictions of drug issues in the United States as wrong. The publication said that due to the ongoing economic crisis, audiences were not open to "downers" and attributed the film's three changes of title to damage control. The article described the positive reception that comedy movies depicting drug culture had in comparison with dramatic ones.[14]

The New York Times gave Cisco Pike a negative review and concluded, "there isn't much to say about it".[15] Newsday said the film "takes itself very seriously", called the script "limited", and criticized Norton for having "no noticeable talent for creating three-dimensional characters".[16] The Washington Post called the plot and the "film's virtue" "mundane".[16] Variety called Cisco Pike "surprisingly good" and Kristofferson "an excellent formal acting debut".[16] Critic Roger Ebert rated it with three stars out of four and wrote that Kristofferson's acting "holds it together".[17] Rolling Stone delivered a favorable review; the writer called Kristofferson "as good an actor, as he is a singer".[8] Los Angeles Free Press considered the filming "faultless".[18]

Cisco Pike was re-released in March 1975 to a short theater run; according to an article in the Los Angeles Times, most of the copies of the film had by then been destroyed. Reviewer Charles Champlin saw the film's depictions as an "accurate slice of social history".[19] After Cisco Pike finished its run in theaters, Columbia Pictures did not license its broadcast for television and it was never officially released on VHS, though bootleg recordings circulated and it was screened in theaters that still possessed original copies. The film was released for the first time on DVD in 2006; Los Angeles Times favored it, accentuating its place in history where "the optimism of the 1960s slips into ... disappointing loneliness". Critic Sean Howe said the movie lacked the exposure it needed to turn it into a cult classic.[13] Nevertheless, Cisco Pike was listed by Danny Peary as one of the emerging cult classics at the last page of his 1981 book Cult Movies.

The website AllMovie gave it three-and-a-half stars out of five; reviewer Fred Beldin said the film is a "feature-length advertisement" for Kristofferson's next album release but concluded it "has plenty to offer with its eccentric pacing, great cast, and period ambiance".[20] Reelfilm gave Cisco Pike two-and-a-half stars out of four and called it "fairly decent". It partly favored Norton's non-linear story approach but said the film is "overwhelmingly meandering and random".[21]

Legacy

In November 2013, the West Hollywood theater Cinefamily hosted a month-long screening of Kristofferson's movies, beginning with Cisco Pike on November 1. The theater held a question-and-answer session with Kristofferson, Stanton and Norton in attendance. Norton described Cisco Pike as his version of La Dolce Vita "set in L.A". Before the film screened, Kristofferson and Stanton performed part of the soundtrack for the audience. The Hollywood Reporter noted the movie gained a cult following and praised Norton for a "clean and defined" plot.[22]

In the third volume of Marvel Comics' Rawhide Kid, the main character's enemy is named after the film and his outfit is called "The Cisco Pike Gang". Marvel's Cisco Pike appears in numbers one to five and inhabits the fictional universe Earth-616.[23]

Soundtrack

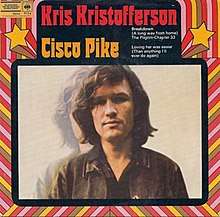

| Cisco Pike | |

|---|---|

| |

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1972 |

| Length | 10:54 |

| Label | Columbia Records (CBS Records 9154) |

The soundtrack of Cisco Pike is mostly composed of songs that would comprise Kristofferson's next album release, The Silver Tongued Devil and I; it includes "Breakdown (A Long Way from Home)", "The Pilgrim—Chapter 33" and "Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Do Again)".[24] An extended play containing the songs was released by Columbia Records in 1972.[25] The film's soundtrack also includes "Michoacan", which is sung by Doug Sahm during his cameo,[26] as well as "Hootin' and Hollerin" by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.[27]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Breakdown (A Long Way from Home)" | 3:29 |

| 2. | "The Pilgrim—Chapter 33" | 3:45 |

| 3. | "Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Do Again) (flipside)" | 3:50 |

See also

Citations

- Lev, Peter 2010, p. 16, 17.

- Alexander Horwath, Thomas Elsaesser, Noel King 2004, p. 95.

- Action Magazine staff 1972, p. 21, 22.

- Alexander Horwath, Thomas Elsaesser, Noel King 2004, p. 96.

- Munn, Michael 1997, p. 49.

- Parish, Robert; Pitts, Michael 2003, p. 463.

- Burke, Tom 1974.

- Streissguth, Michael 2013, p. 90.

- Taylor, Charles 2017, p. 31.

- AFI staff 2019.

- Shelley, Peter 2018, p. 37.

- Columbia staff 1972.

- Howe, Sean 2006.

- Darrach, Brad 1971, p. 82.

- Canby, Vincent 1972.

- Filmfacts staff 1972, p. 20.

- Ebert, Roger 1972.

- Kent, Andy 1971, p. 16.

- Champlin, Charles 1975, p. 54.

- Beldin, Fred 2006.

- Nusair, David 2006.

- Hundley, Jessica 2013.

- Phillips, Nickie; Strobl, Staci 2013, pp. 154–156.

- Strong, Martin Charles; Griffin, Brendon 2008, p. 212.

- 45cat staff 2020.

- Kubernik, Harvey 2006, p. 89.

- Krampert, Peter 2016, p. 172.

General references

- 45cat staff (2020). "Kris Kristofferson - Cisco Pike - Monument - UK". 45cat. 45cat Website. Retrieved March 17, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Action Magazine staff (1972). "Cisco Pike". Director's Guild of America. DGA Publication's Committee.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- AFI staff (2019). "CISCO PIKE (1972)". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute. Retrieved March 18, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alexander Horwath, Thomas Elsaesser, Noel King (2004). The Last Great American Picture Show: New Hollywood Cinema in the 1970s. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-905-356631-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beldin, Fred (2006). "Cisco Pike (1971)". Allmovie. AllMovie, Netaktion LLC. Retrieved March 17, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burke, Tom (1974). "Kris Kristofferson's Talking Blues". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media LLC. Retrieved March 16, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Canby, Vincent (1972). "'Cisco Pike':Tale of Has-Been Rock Star Opens at Forum". New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved March 17, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Champlin, Charles (March 11, 1975). "A Second Chance for Cisco Pike". Los Angeles Times. 94. Nant Capital, LLC.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Columbia staff (1972). Cisco Pike EP (sleeve). Kris Kristofferson. Columbia Records. CBS Records 9154.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Darrach, Brad (1971). "Now at your local theater: A new kind of shoot-'em-up". Life Magazine. Time Inc. 71 (19). Retrieved March 17, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ebert, Roger (1972). "Cisco Pike". Retrieved March 17, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Filmfacts staff (1972). "Cisco Pike". Filmfacts. Division of Cinema of the University of Southern California. 15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howe, Sean (2006). "The Celluloid Time Capsule". LA Times. Los Angeles Times Company. Retrieved March 17, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hundley, Jessica (2013). "Kris Kristofferson, Harry Dean Stanton Revisit 1972's 'Cisco Pike'". Hollywood Reported. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved March 17, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kent, Andy (1971). "Silver Tongued Devil". Los Angeles Free Press. 8 (370). Part 2. Retrieved May 7, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kubernik, Harvey (2006). Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music in Film and on Your Screen. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0826-33542-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krampert, Peter (2016). The Encyclopedia of the Harmonica. Mel Bay publications. ISBN 978-1-619-11577-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lev, Peter (2010). American Films of the 70s: Conflicting Visions. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77809-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Munn, Michael (1997). Gene Hackman. Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-709-06041-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nusair, David (2006). "Cisco Pike (January 31/06)". Reelfilm. David Nusair. Retrieved March 17, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parish, Robert; Pitts, Michael (2003). Hollywood Songsters: Garland to O'Connor. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-94333-8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Phillips, Nickie; Strobl, Staci (2013). Comic Book Crime: Truth, Justice, and the American Way. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-814-76452-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Charles (2017). "Farewell to the first Golden Era: Cisco Pike". Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You: The Shadow Cinema of the American '70s. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-632-86817-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shelley, Peter (2018). Gene Hackman: The Life and Work. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-476-63369-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Streissguth, Michael (2013). Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-062-03820-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strong, Martin Charles; Griffin, Brendon (2008). Lights, camera, sound tracks. Canongate. ISBN 978-1-847-67003-8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)