Chu Shijian

Chu Shijian (Chinese: 褚时健; 17 January 1928 – 5 March 2019) was a Chinese business executive and entrepreneur, known as the "king of tobacco" and the "king of oranges". He turned the near-bankrupt Yuxi Cigarette Factory into one of China's most profitable state-owned companies and developed its Hongtashan cigarette into one of the country's most valuable brands. At its peak, the company contributed 60% of total revenues of the Yunnan provincial government.[1]

Chu Shijian | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

褚时健 | |||||||||||

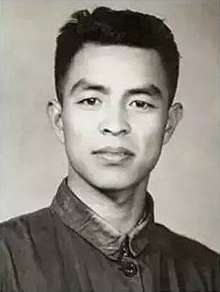

Chu Shijian in 1952 | |||||||||||

| Born | 17 January 1928 Yuxi, Yunnan, China | ||||||||||

| Died | 5 March 2019 (aged 91) Yuxi, Yunnan, China | ||||||||||

| Occupation | Business executive, entrepreneur | ||||||||||

| Known for | Orange King Tobacco King | ||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 褚時健 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 褚时健 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Chu supplemented his low official salary by taking bribes. He was arrested for corruption in 1996 and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1999. After being released on medical parole in 2002, he started his second company at age 75, an orange plantation with the brand name "Chu Orange". It became a nationally famous brand, giving Chu a new nickname as the "king of oranges". His achievements and unyielding spirit made him "one of China's most iconic entrepreneurs".[1]

Early life

Chu was born on 17 January 1928[2] in Yuxi, Yunnan, Republic of China.[3] He participated in the Chinese Communist Revolution in his youth, but was later denounced as a "rightist" during the Anti-Rightist Campaign, and was not politically rehabilitated until the end of the Cultural Revolution.[4] He managed a sugar cane factory in his early career.[5]

Career

Yuxi Tobacco

In October 1979, Chu was appointed head of Yuxi Cigarette Factory (later known as Yuxi Tobacco Company and Hongta Group). Yuxi was a near-bankrupt state-owned factory that made the Hongtashan (Red Pagoda Hill) brand of cigarettes,[3][6] with an annual revenue of less than US$1 million.[7]

Chu recognized that as China's economy was starting to grow, more people could afford cigarettes, and he began to promote the Hongtashan brand all over the country. The brand became famous and demand grew quickly. Chu was able to sell the cigarettes for US$1.5 to $2 per pack, although the official price was fixed at $1.[7] He spent the unreported profit on buying state-of-the-art equipment and building new offices and apartments for his employees.[7]

By 1995, the company produced more than 100 billion cigarettes per year but still could not meet the demand even at the higher unofficial prices. Wholesalers were willing to pay bribes to Chu and his family members to secure supplies of Hongtashan.[7] While Yuxi Tobacco generated more than 99 billion yuan in profits and taxes for the government during his 16-year tenure,[6] Chu's official monthly salary was less than US$250.[7] He and his family members could not resist the temptation of augmenting their income by taking bribes. In February 1995, an informant sent evidence of the illegal payments to the government.[6] Chu's wife Ma Jingfen (马静芬) and their daughter Chu Yingqun (褚映群) were arrested, and Yingqun committed suicide in prison.[7]

Chu was arrested in 1996. In 1999,[1] he was convicted of embezzling US$1.74 million and diverting more than $145 million to company accounts from state coffers.[6][7] He was sentenced to life imprisonment, although many considered it unjust and he remained a popular hero in Yuxi.[6][7] His sentence was later reduced several times and officially ended in 2011.[1]

Chu Orange

Chu developed diabetes while in prison and was released in 2002 on medical parole. Already 74, he decided to start his second company, an orange farm.[6]

In June 2003, he leased 134 hectares (330 acres) of land in Xinping County and hired 300 employees.[6][8] He employed the same management methods as at Yuxi Tobacco, such as the emphasis of quality over quantity and linking workers' income to the company's profits. As the company grew, his employees were able to earn several times the average local wage.[5] He used the Internet to market his "Chu Oranges" nationally,[8] and attracted wealthier customers who were willing to pay higher prices for a premium brand perceived as nutritious and safe. The company became highly successful, selling 10,000 tons of oranges a year by 2013.[5] He also developed his orange plantation in the Ailao Mountains into an ecotourism resort.[8] Chu, already known as the "tobacco king" of China, gained another title as the "king of oranges".[5][9]

On 17 January 2018, his 90th birthday, Chu appointed his son Chu Yibin (褚一斌) as chief executive officer of Chu's Fruit Company Limited, while he retained the title of chairman.[2]

Death

On 5 March 2019, Chu died from complications from diabetes[10] at Yuxi People's Hospital.[2] He was 91.[3]

References

- Tang, Frank (2019-03-06). "'An extraordinary man': China's tobacco king Chu Shijian dies aged 91". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Yao Xiaolan 姚晓岚 (2019-03-05). "褚橙创始人褚时健去世:享年91岁,曾被称为中国烟草大王". Thepaper.cn. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- "China's 'tobacco king', Chu Shijian, dies aged 91". China Daily. 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-06.(subscription required)

- Wu Guixia 吴桂霞 (2012-12-05). "褚时健84岁再成亿万富翁 唯一女儿1996年狱中自杀". Phoenix News. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- O'Neill, Mark (2014-01-16). "From tobacco king to emperor of oranges". EJ Insight. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- O'Neill, Mark (2010-06-03). "How tobacco king turned to oranges". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- Faison, Seth (1998-03-06). "China's Paragon of Corruption; Meet Mr. Chu, a Hero to Some, an Embezzler to Others". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-03-06.(subscription required)

- Ye, Qiongwei; Ma, Baojun (2017). Internet+ and Electronic Business in China: Innovation and Applications. Emerald Publishing Limited. pp. 143–4. ISBN 978-1-78743-115-7.

- "Chinese 'orange king' dies at the age of 91". China.org.cn. 2019-03-05. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- ""中国烟草大王"褚时健病逝". Radio Free Asia (in Chinese). 2019-03-05. Retrieved 2019-03-06.