Chipping sparrow

The chipping sparrow (Spizella passerina) is a species of American sparrow, a passerine bird in the family Passerellidae. It is widespread, fairly tame, and common across most of its North American range.

| Chipping sparrow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult in breeding plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Passerellidae |

| Genus: | Spizella |

| Species: | S. passerina |

| Binomial name | |

| Spizella passerina (Bechstein, 1798) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Spizella socialis | |

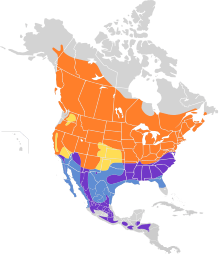

There are two subspecies, the eastern chipping sparrow and the western chipping sparrow. This bird is a partial migrant with northerly populations flying southwards in the fall to overwinter in Mexico and the southern United States, and flying northward again in spring.

It molts twice a year. In its breeding plumage it has orangish-rust upper parts, gray head and underparts and a distinctive reddish cap. In non-breeding plumage, the cap is brown and the facial markings are less distinct. The song is a trill and the bird has a piercing flight call that can be heard while it is migrating at night.

In the winter, chipping sparrows are gregarious and form flocks, sometimes associating with other bird species. They mostly forage on the ground for seeds and other food items, as well as clambering on plants and trees, feeding on buds and small arthropods. In the west of their range they breed mainly in coniferous forests, but in the east, they choose woodland, farmland, parks and gardens. Breeding starts in late April and May and the nest is often built in a tree.

Description

Throughout the year, adults are gray below and an orangish-rust color above. Adults in alternate (breeding) plumage have a reddish cap, a nearly white supercilium, and a black trans-ocular line (running through the eye). Adults in basic (nonbreeding) plumage are less prominently marked, with a brownish cap, a dusky eyebrow, and a dark eye-line.

Juvenile chipping sparrows are prominently streaked below. Like non-breeding adults, they show a dark eye-line, extending both in front of and behind the eye. The brownish cap and dusky eyebrow are variable but generally obscure in juveniles.

Vocalizations

The song is a trill that varies considerably among birds within any particular region. Two broad classes of variation in the song of the chipping sparrow are the fast trill and the slow trill. Individual elements in the fast trill are run together about twice as fast as in the slow trill; the fast trill sounds like a buzz or like someone snoring, whereas the slow trill sounds like rapid finger-tapping. Individual elements in the trill are very similar to a high pitch chi chi chi call.

The flight call of the chipping sparrow is heard year-round. Its flight call is piercing and pure-tone, lasting about 50 milliseconds. It starts out around 9 kHz, then falls to 7 kHz, then rises again to 9 kHz. The flight call may be transliterated as seen? Chipping sparrows migrate by night, and their flight calls are a characteristic sound of the night sky in spring and fall in the United States. In the southern Rockies and eastern Great Plains, the chipping sparrow appears to be the most common nocturnal migrant, judged by the number of flight calls detected per hour. On typical nights in August in this region, chipping sparrows may be heard at a rate of 15 flight calls per hour. On better-than-average nights, chipping sparrows occur at a rate of 60 flight calls per hour, and on exceptional nights chipping sparrows' flight calls are heard more than 200 times per hour.

Taxonomy

Chipping sparrows vary across their extensive North American range. There is minor geographic variation in appearance, and there is significant geographic variation in behavior. Ornithologists often divide the chipping sparrow into two major groups: the eastern chipping sparrow and the western chipping sparrow. However, there is additional plumage and behavioral variation within the western group.

At least two subspecies of chipping sparrows occur in western North America. The widespread Spizella passerina arizonae is associated with mountains and arid habitats of the western interior. A Pacific slope population constitutes subspecies S. p. stridula. Although these two races are both western, and are often lumped together as the western chipping sparrow, they do not necessarily form a single entity that stands apart from the eastern chipping sparrow (S. p. passerina).

The chipping sparrow is part of the family Emberizidae, and is not closely related to the Old World sparrows of the family Passeridae.[2]

Breeding

The male chipping sparrow start arriving at the breeding grounds from March (in more southern areas, such as Texas)) to mid-May (in southern Alberta and northern Ontario). The female arrives one to two weeks later, and the male starts singing soon after to find and court a mate.[3] After pair formation, nesting begins (within about two weeks of the female's arrival). Overall, the breeding season is from March till about August.[4]

The chipping sparrow breeds in grassy, open woodland clearings[3] and shrubby grass fields.[4] The nest is normally above ground but below 6 metres (20 ft) in height,[3] and about 1 metre (3.3 ft) on average,[5] in a tree (usually a conifer, especially those that are young, short, and thick) or bush. The nest itself is constructed by the female[3] in about four days.[5] It consists of a loose platform of grass and rootlets and open inner cup of plant fiber and animal hair.[4]

The chipping sparrow lays a clutch of two to seven pale blue to white eggs with black, brown, or purple markings. They are about 17 by 12 millimetres (0.67 by 0.47 in), and incubated by the female for 10 to 15 days.[4] The chipping sparrow is often brood parasitized by brown-headed cowbirds, usually resulting in the nest being abandoned.[3]

Feeding

The chipping sparrow feeds on seeds year-round, although insects form most of the diet in the breeding season. Spiders are sometimes taken. Taraxacum officinale seeds are important during spring, and seeds from Fallopia convolvulus, Melilotus spp., Stellaria media, Chenopodium album, Avena spp., and others.[3]

Throughout the year, chipping sparrows forage on the ground[6] in covered areas,[7] often near the edges of fields.[3]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Spizella passerina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Allende, Luis M.; Rubio, Isabel; Ruíz-del-Valle, Valentin; Guillén, Jesus; Martínez-Laso, Jorge; Lowy, Ernesto; Varela, Pilar; Zamora, Jorge; Arnaiz-Villena, Antonio (2001). "The Old World sparrows (genus Passer) phylogeography and their relative abundance of nuclear mtDNA pseudogenes" (PDF). Journal of Molecular Evolution. 53 (2): 144–154. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.520.4878. doi:10.1007/s002390010202. PMID 11479685. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.

- Rising, J. (2018). del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi; Christie, David A.; de Juana, Eduardo (eds.). "Chipping Sparrow (Spizella passerina)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Hauber, Mark E. (1 August 2014). The Book of Eggs: A Life-Size Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World's Bird Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 581. ISBN 978-0-226-05781-1.

- Reynolds, John D.; Knapton, Richard W. (1984). "Nest-site selection and breeding biology of the chipping sparrow". The Wilson Bulletin. 96 (3): 488–493. ISSN 0043-5643.

- Allaire, Pierre N.; Fisher, Charles D. (1975). "Feeding ecology of three resident sympatric sparrows in eastern Texas". The Auk. 92 (2): 260–269. doi:10.2307/4084555. ISSN 0004-8038. JSTOR 4084555.

- Lima, Steven L.; Valone, Thomas J. (1991). "Predators and avian community organization: an experiment in a semi-desert grassland". Oecologia. 86 (1): 105–112. doi:10.1007/BF00317396. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 28313165.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to the chipping sparrow. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Spizella passerina |

- Chipping sparrow – Spizella passerina – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Chipping sparrow species account – Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology

- "Chipping sparrow media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Chipping sparrow photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Spizella passerina at IUCN Red List maps